With over 41,000 residents, Camp Bowie in Fort Worth was a city within a city. As with all cities, change was normal in Camp Bowie. After the consolidation of the eight infantry regiments into four big ones, the next big change was transfers.

While the original soldiers of the 36th Infantry Division were National Guard volunteers, that distinction soon changed. In November 1917, five thousand draftees were transferred to Camp Bowie from Camp Travis in San Antonio and Camp Dodge in Iowa.

By this time training was in earnest and officers and non-commissioned officers were sent off-base for training at special schools across the country. Camp Bowie also hosted a number of British and French officers and noncoms who helped train the men.

American Industry steps up

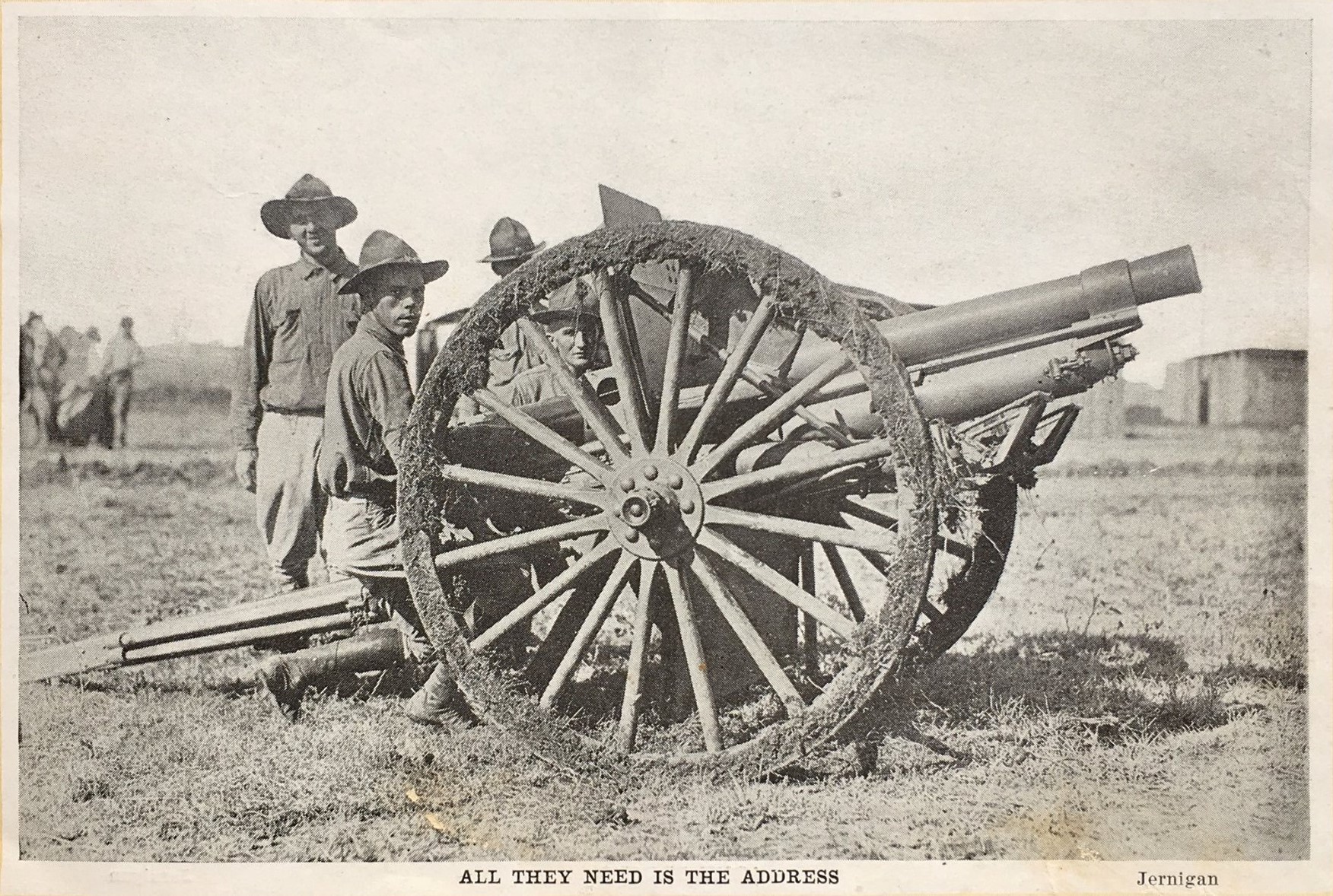

By 1918, weapons and equipment were beginning to arrive at Camp Bowie. The Division’s first six artillery pieces arrived in January and February. Rifles were more plentiful after the beginning of the year as well. But there were still shortages of weapons and ammunition. Two more cannon arrived in April, but the 61st Field Artillery Brigade was not fully equipped until June.

Officers of the 36th Infantry Division kept the men busy training while waiting for equipment to arrive. Soldiers could expect long hikes, simulated battles, and instruction in trench warfare. This included gas mask drills, cutting through barbed wire, and using Camp Bowie’s ten mile-long trench system.

As 1918 wore on the Division received motor trucks, wagons and communications equipment. The men also trained to proficiency with their rifles, squad automatic rifles and machine guns. But it would not be until June when every rifleman in the division had his own rifle.

Division in review

By the spring of 1918 the 36th Infantry Division was approaching readiness. Ready, but not sent overseas. Other Divisions that trained in Texas, for example the 32nd Infantry (Camp MacArthur in Waco), 33rd Infantry (Camp Logan in Houston) and the 90th Infantry (Camp Travis in San Antonio), were already transferred to France. Some in and outside Camp Bowie wondered if they would ever get there.

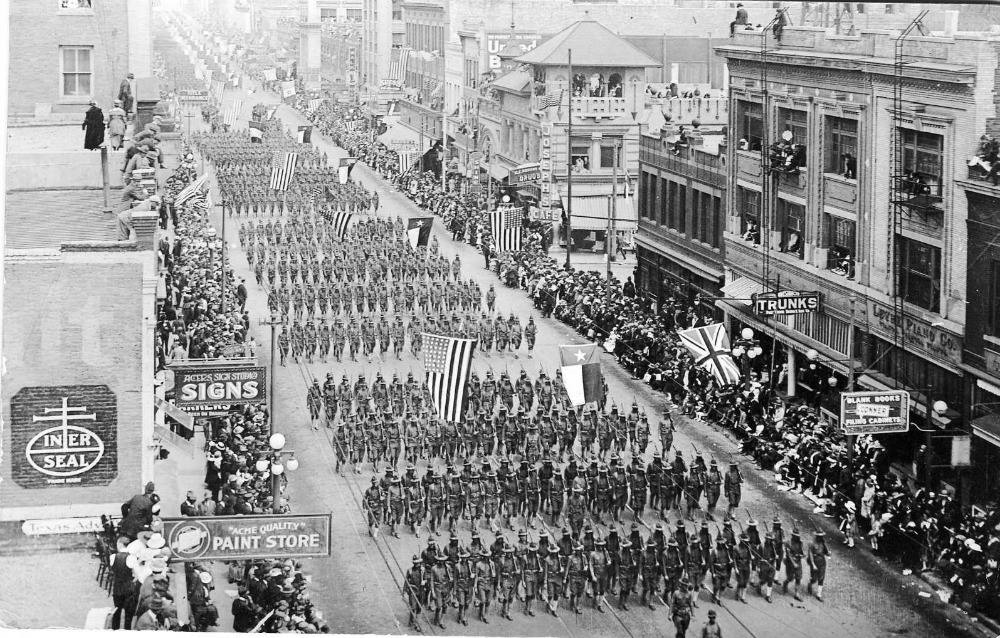

In the meantime, Fort Worth got to see their Sammies on parade. On April 11th, about 25,000 of them, along with 1,200 vehicles and 5,000 horses passed in a miles-long review before the multitudes. In the proud column was Otho Farrell of Headquarters Company, 142nd Infantry, who had just been promoted Corporal on April 5th.

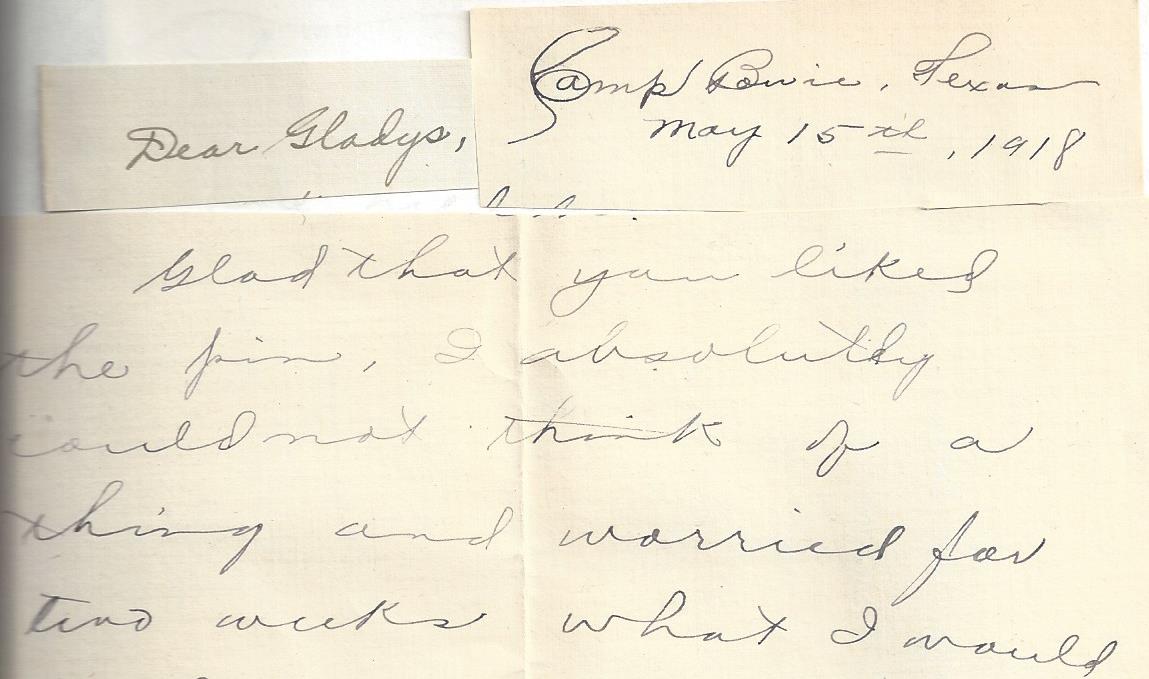

Otho wrote a letter to Gladys Loper, a friend of his sisters’ in Waynoka, OK around this time. She was about to graduate High School and was thinking about her future.

Mobilized

Men of the 36th Infantry Division could sense things were changing. Five thousand men, draftees from Texas, Oklahoma and Kansas, were added in May. That month, the War Department gave the division orders to be ready to move on short notice. In June, the men were drilling for immediate deployment, packing and moving to departure points. They knew it was the real thing when they were issued new dog tags that did not include their unit name.

At last, on July 2nd, the order to leave Camp Bowie was received. For ten months Fort Worth and Camp Bowie were home to the 36th Infantry Division. In late summer 1917, this was a largely untested mass of Guardsmen, volunteers all. They were practically the entire National Guard of both Texas and Oklahoma; just as diverse as the lands they represented.

Although they were volunteers and Guardsmen, they felt adequately prepared. Their morale was high and, despite all hazards of the previous year, had formed into a force they believed was equal to the fight. Texas and Oklahoma expected no less.