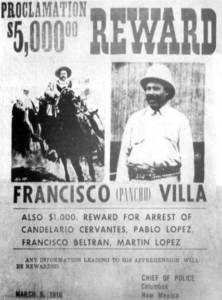

When the United States went to war with Germany in April 1917, conflict was already part of life along its border with Mexico. The Mexican Revolution reached a high point late in 1915, when the Wilson Administration recognized Venustiano Carranza as president. But Carranza’s former compañero, Francisco “Pancho” Villa, was having none of it.

The Border War

Villa, who sometimes went over the U.S. border to buy weapons and evade rival Mexican troops, nursed a grudge. The U.S. helped his rival Carranza and now he sought revenge. Consequently, on January 11, 1916, Villa stopped a train in Northern Mexico, removed sixteen American mining engineers from the coaches, and shot them. He had already shot at Americans in border clashes. Most noteworthy, on March 6, his men attacked the U.S. Cavalry barracks and the town of Columbus, New Mexico. Sixteen U.S. citizens were killed in the raid. As a result, 6,675 U.S. Army soldiers went into pursuit from San Antonio the next week. Their leader was Brigadier General John J. Pershing.

It was the beginning of a 400-mile incursion into neighboring Mexico. It lasted eleven months and grew to fourteen thousand U.S. troops. After many battles with the Villistas and even attacks from President Carranza’s men, Pershing was recalled. The mission was risking war with Mexico. They never caught up to Villa. Finally, the U.S. expedition returned to Texas on February 5, 1917. (Wilson and his Secretary of State on the crisis can be read here.)

Mobilizing the Guard

While the regular U.S. Army was off fighting in Mexico the National Guard, a new creation, was holding the fort in the Southwest. Guard units from Texas, New Mexico, Arizona and as far off as Massachusetts were mobilized and sent to protect the border. A total of 140,000 Guardsmen from fourteen states and the District of Columbia mobilized for the emergency. Although some Guard troops crossed the border to resupply Pershing’s forces, none fought in Mexico.

The border war showed how badly stretched the regular U.S. Army was in 1916-1917. But it also revealed a new ability in its National Guard. While protecting the border, Guard units were brought into conformity with national training and discipline standards. They became familiar with new equipment and tactics. Officers were required to coordinate with other units in complex formations. Moreover, commanders learned to lead larger forces. Consequently, time spent in the Southwest would mean something in the future.

For the border states themselves, the emergency was no quasi-war. Dozens of border incursions and battles occurred between 1915 and 1917. One example being the bloody raid on Glenn Springs, Texas on May 5-6, 1916. Civilians were killed. The entire Texas National Guard began serving on the border in May 1916. It was ordered off the line in March 1917. During the emergency it was not completely out of the question that events would result in a wider war. Texas newspapers speculated what help President Carranza was getting from Germans in Mexico City. Even more, some published rumors of German advisers in Villa’s army. (An excellent summary of the Border Crisis is here.)

Deployment and Redeployment

Just a week after the Texas and Oklahoma National Guard units returned from their long deployment, they deployed again. The crisis with Germany ran into the present one with Mexico. Texas and Oklahoma guardsmen headed back to the border. This time they wouldn’t be back until October. By then the whole world had changed.

In 1914 people in the Southwest may have felt that the war in Europe was too far away to be a concern. In April 1917, they wondered if this was to be the new front line.

Meanwhile, on April 10th, eighteen tons of black powder exploded in an ammunition factory in Pennsylvania. As had happened before, the initial explosion touched off dozens of secondary ones, hindering rescue efforts. Most of the workers at the Eddystone Artillery Factory were women and girls. Hundreds were injured and burned, and 139 were killed.

The war was only four days old.