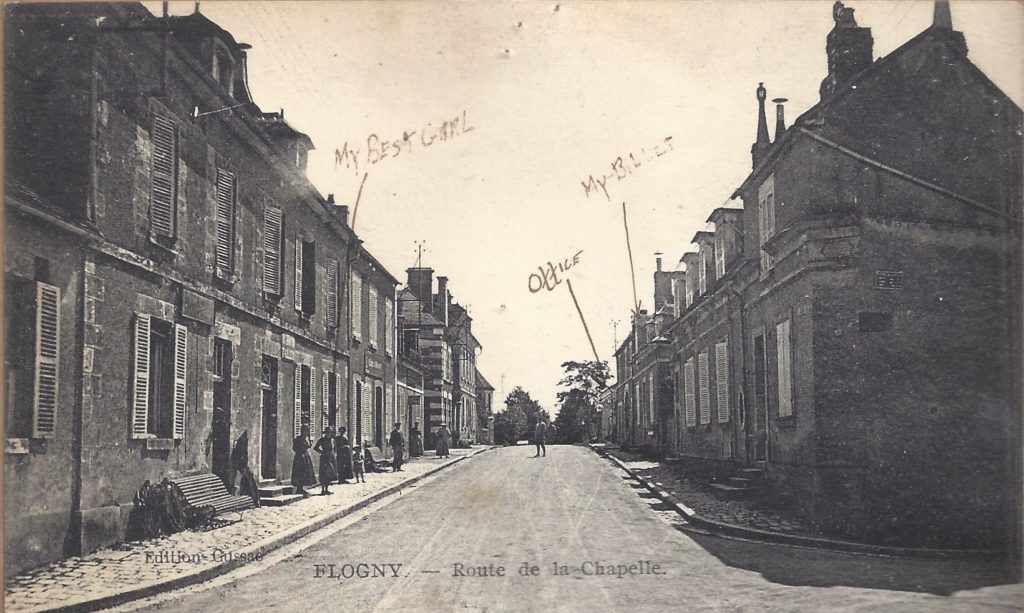

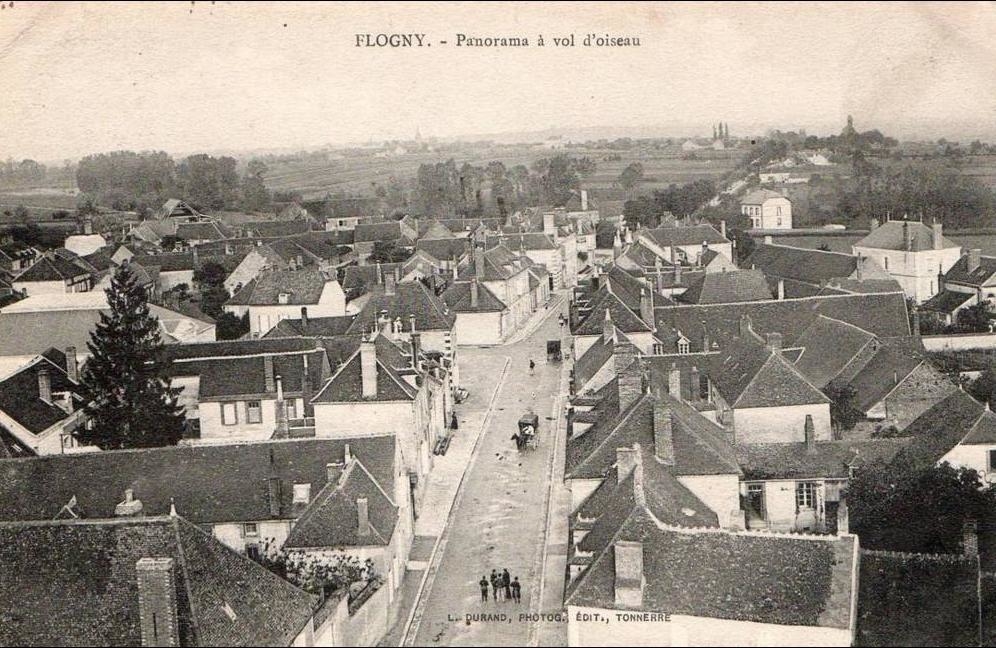

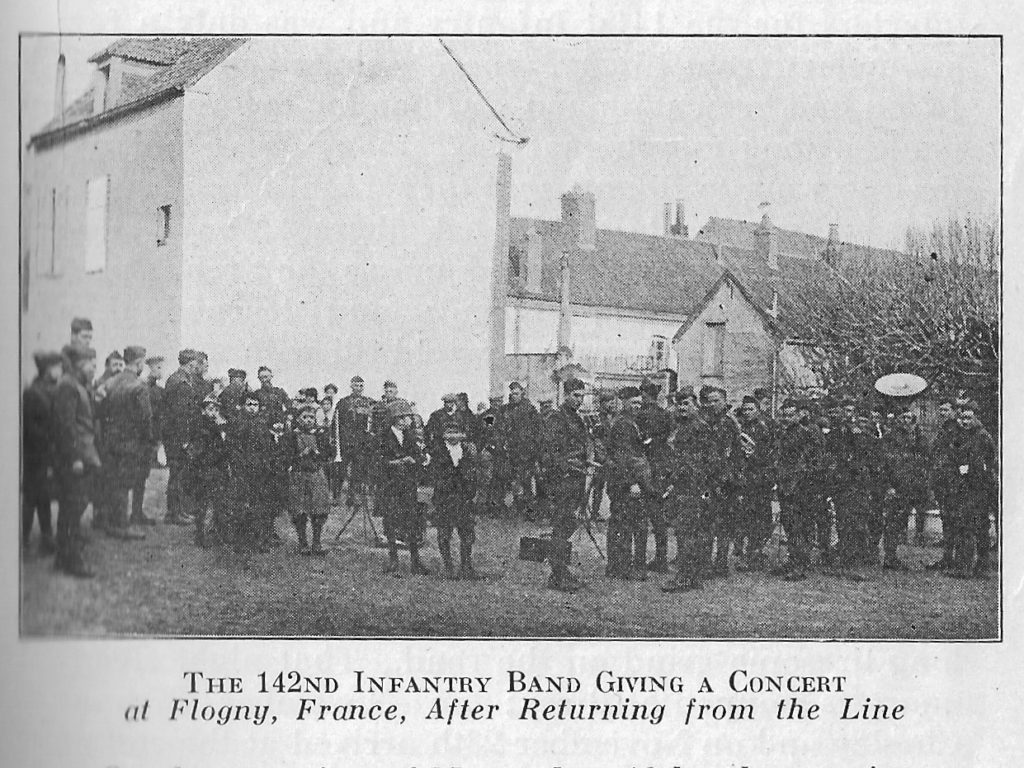

“Geese…Chickens cackling…Bread wagon horn…Bell at gate…Soldiers cussing…Dog barking…Truck passing on highway…French people talking…Small French kid whistling…Creak of farmer’s wagon…Wooden shoes on hard ground…Cattle mooing…Rooster crooning…Chain on well…Wheelbarrow squeaking.” Ed Sayles of Abilene wrote about French country living while stationed near Flogny, France after the Armistice. As a lieutenant, he commanded the 37mm Gun platoon during the fighting. Captain Sayles was now a company commander in the 142nd Infantry.

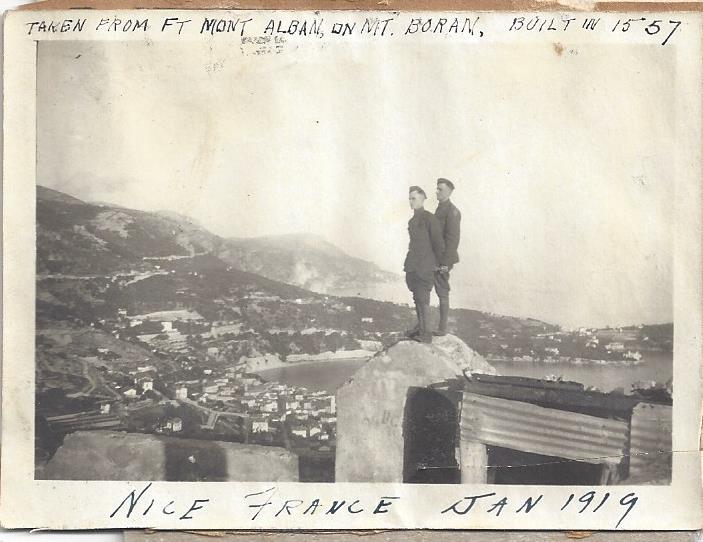

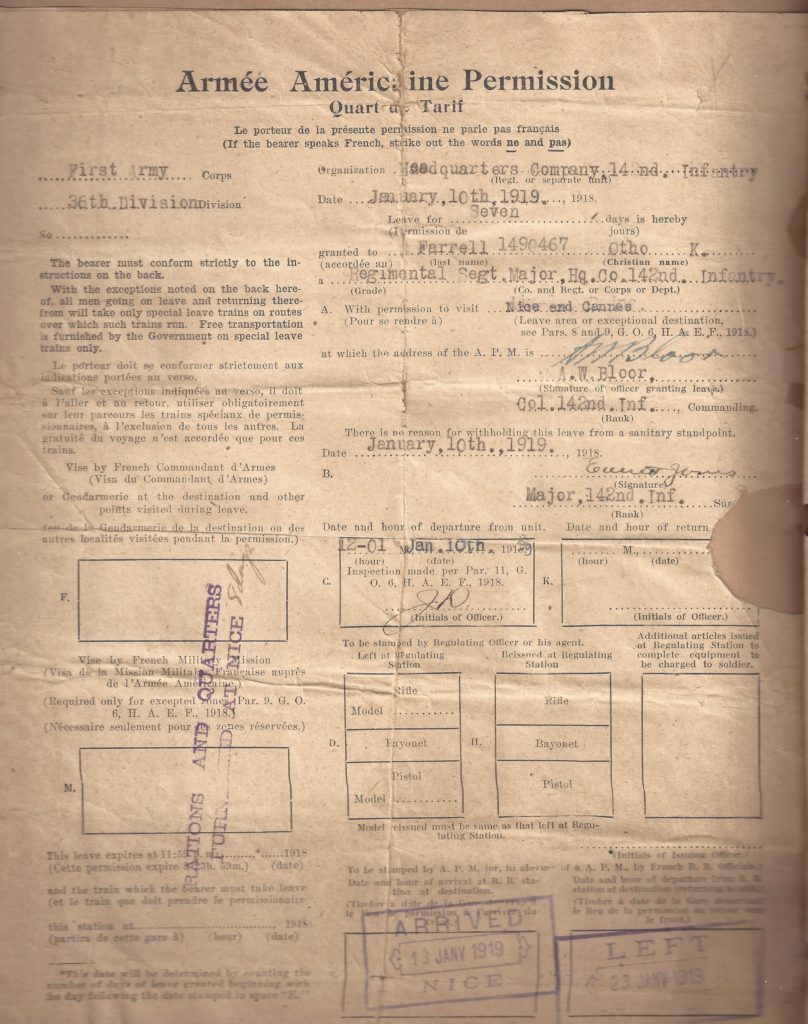

The 142nd Infantry Regiment and the rest of the 36th Infantry Division was quartered with two other divisions at the Sixteenth Training Area in the Département of Yonne in northeastern France. The 142nd Infantry Headquarters Company and Medical Detachment were located in the town of Flogny. 1st Battalion Headquarters and Companies A and B were billeted in Percey. Companies C and D were located at La Chapelle-Vieille-Forêt. 2nd Battalion Headquarters and Companies E and F were in Carisey. Companies G and H were billeted in Villiers-Vineux. 3rd Battalion Headquarters, the Machine Gun Company and Companies I, K, and L were located in Lignières. The Supply Company and Company M were billeted at Marolles-sous-Lignières.

Winter sets in

The men of the 36th Infantry Division were beginning a long residence in eastern France in the winter of 1918-1919. Before they began their 130-mile march from the front, the 36th received about 3,600 replacement soldiers. Most of the replacements were in good health and in good spirits. However, the long march did take a toll on the men’s feet. Boots wore out for greenhorn and veteran alike. Many of the men had essentially nothing to walk in by the time they reached their living quarters, so they stayed indoors until new boots arrived.

As it was also winter, some of the new men were beginning to get sick. Close living arrangements with what amounted to a bunch of strangers was toughest on the replacements. The unit hospitals began to fill up. It was around this time that the global influenza pandemic once again reached the 36th Division. It had hit the 36th Division when it was stationed near Bar-sur-Aube in September 1918. Fifteen men from the 142nd died in the hospital that fall from influenza or the pneumonia that came after it. Five men from the 142nd died in hospital in the winter of 1919.

POWs

Ten men from the 142nd Infantry were missing in action in the fighting of October 8-28. In fact, these men were Prisoners of War in Germany. About 2,450 American soldiers, marines and airmen were POWs in Germany. There were also U.S. sailors and merchant marines, making the total 4,120 held captive. When the Armistice was signed, Germany agreed to the immediate release of Allied POWs. (Read more about the American POW experience here.)

The way home from POW camps in Germany was sometimes chaotic and improvised. Most American soldiers, marines and airmen were transferred through Switzerland to France by the International Committee of the Red Cross. American sailors and merchant marines traveled by sea to England. Therefore in early 1919 ten came back to the 142nd, including Privates John Martin and Joseph Krepps and Sergeant Norman Duff of Company A. They had been captured in Saint Étienne on October 8. Also returned was Private Buster L. Stinson of Company C, captured during a daylight patrol on the wrong side of the Aisne on October 21, 1918.

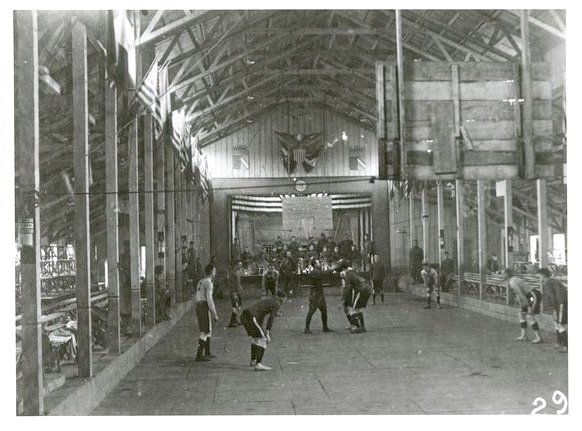

Basketball

As much as the 36th Division enjoyed football, it was now basketball season. The division had 68 basketball teams spread across their encampment. In all the competition across the division, no one could beat the top five players in the 142nd Infantry Regiment. The 142nd All-Star team ended up winning the 36th Division crown and went on to beat their neighbors, the 80th Infantry Division. However at the I Corps championships, the 36th Division team lost to the 78th Infantry Division team, 20-28.