While Texas and Oklahoma soldiers were training at Camp Bowie in Fort Worth, a Texas unit was already serving in France.

Created the 1st Texas Supply Train in the spring of 1917, it was to be the motor transport unit of a new Texas National Guard Division then taking shape. The unit had six companies across the state in Houston, Austin, Dallas and Big Spring. They trained that summer in anticipation of joining other Texas National Guard units at Camp Bowie in September. They were organized this way:

Headquarters Detachment Houston

Motor Truck Company No. 1 Dallas

Motor Truck Company No. 2 Austin

Motor Truck Company No. 3 Houston

Motor Truck Company No. 4 Big Spring

Motor Truck Company No. 5 Dallas

Motor Truck Company No. 6 Houston

Instead the six companies and headquarters section of the 1st Texas Supply Train were federalized on August 5th and sent east to Long Island, New York.

There, in Camp Mills, National Guard units from 26 states and the District of Columbia were gathered as one of the first divisions to be sent overseas: the 42nd Infantry Division.

Shipping out

At Camp Mills, the 1st Texas Supply Train became the 117th Supply Train. The 42nd Infantry Division left Hoboken, New Jersey for France beginning in late October, 1917. The whole division was in France by December. With the most basic of training stateside, the 42nd spent six weeks in eastern France at a training camp near Vaucouleurs.

One of the infantry regiments of the 42nd Division was the 165th Infantry, better known as the 69th New York. The “Fighting 69th” began a decade before the Civil War as a New York militia unit, the 2nd Irish Regiment. By the summer of 1862, the unit was known as “The Fighting Irish” to their Confederate opponents around Richmond, Virginia.

42nd’s Valley Forge

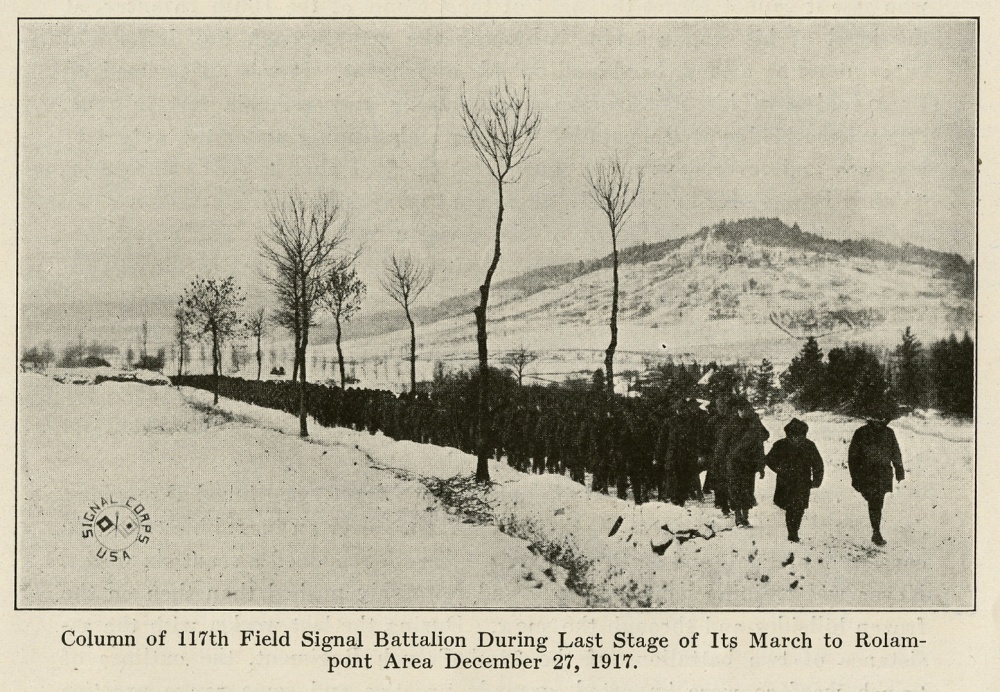

By the end of 1917, American Expeditionary Forces commander General John Pershing had 183,896 American servicemen in France. Shortly after celebrating Christmas, the 42nd Division received orders to move to Rolampont, over 40 miles away. Rolampont was the site of the Army’s Seventh Training Area. It was winter; snow covered the roads, and they had to walk.

Welcome to Valley Forge.

The temperature in this hilly region of eastern France was frigid and the men were ill-equipped. A winter storm blew in. Boots wore out, extra supplies used up. Also, not every man had an overcoat. Texans of the 117th Supply Train, a motor truck unit, had to haul the division’s gear the old fashioned way, by horse and wagon.

Wagons got stuck in the snow; men huddled in barns and haylofts at night. For some men, food ran out after the first day. Furthermore, men of the supply train had to move their best horses and mules from wagon to wagon to pull them out of snowdrifts. Overburdened men grew exhausted and fell out of line.

Over the hills and through the snow

As the temperatures sank below zero, men were coming down with mumps and pneumonia. Hundreds were falling behind from exhaustion. The region they marched through was in the foothills of France’s Vosges mountains. Above all, the passage to Rolampont tested men and their early 20th-Century equipment to extremes. Worn out boots were discarded because of swollen feet, evoking images of the real Valley Forge during the winter of 1777-78.

It took most units four days to make the trek through the frozen countryside of France. By New Year’s day 1918, the whole division had reached Rolampont. Although it was an arduous introduction to war, the 42nd Infantry Division would have to adapt. Moving to the front early in 1918, the 42nd would spend 198 days of that year at the front.