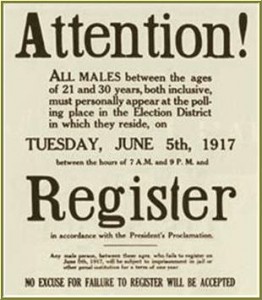

Woodrow Wilson signed the Selective Service Act on May 18, 1917. It called for all men between the ages of 21 and 30 to register before one of 4,648 local draft boards across the country on June 5th. The bill was vigorously debated in Congress and elsewhere. There had not been a draft in the United States since the Civil War. Wilson initially hoped that American men would volunteer for the armed forces once war was declared. However in the first ten days of the war, only 4,355 of them nationwide had stepped forward.

Supporters of the draft

There was plenty of debate about the draft in northwest Texas and the Panhandle. While the region was unabashedly patriotic, drafting all military-age men exposed differences where parades and speeches recently showed unity. Supporters of the draft believed it was fairer, as it applied to all eligible men. Place of residence or economic class or connections were leveled in the draft system, in argument at least.

The draft was also more reasonable, supporters maintained. The call to service to draftees would be orderly and staggered over time so as not to disrupt the social fabric of any one community more than another. Thus the draft would be free from undue emphasis on emotion and hyper-patriotism. Young men would be called to serve in their time, and not all at once. There would be no “buyer’s remorse” of volunteers who were caught up in a wave of enthusiasm.

Critics of the draft

Opponents in Texas argued the draft was disruptive. Small farms depended on able bodied family members for their livelihood. A family farm could rarely afford to pay a farmhand. Family businesses were in the same situation. Opponents of the draft thus drew attention to the disproportionate effect the draft would have on rural communities in Texas. Farmers and factory workers were necessary for the war effort. Drafting them would unnecessarily lengthen the war.

Detractors also saw the draft as undemocratic, as men were brought into federal service against their free will. This was troubling to many Texans, who valued individual freedom. Some initially argued there would be no need for the draft. Plenty of young men would volunteer in a state with a military heritage such as Texas. The idea of a democracy with a compulsory draft did not make sense to many.

Opponents were also wary of militarism, one of the evils President Wilson claimed to be warring against. Creating an army of conscripts put the nation on a perpetual war footing. This militarism, critics argued, went hand-in-glove with what was perceived in Texas as a pro-war arms cartel in the East. If Wilson gave in to militarism, the draft could become permanent and future foreign wars more likely. Texas Congressman Jeff McLemore, a Democrat, argued on Capitol Hill that the “establishment and perpetuation of a military system in this country will soon see the end of our republican form of government.”

(More about the conscription debate here.)

Registration day approaches

Recruiters for the armed forces did not wait. The U.S. Navy opened recruiting stations in five northwest and Texas Panhandle counties. Recruiters for all the branches also traveled the roads and rails, looking for volunteers in small towns and ranches. The response in May 1917 was enthusiastic: 1,867 men volunteered across North Texas.

In addition to choosing among the U.S. Army, Navy and Marines, young men could also wait to be drafted. If drafted, they would likely serve as riflemen in the army. If one wanted another assignment, he would have to enlist. Another option was to apply for officer training camps the army was building nationwide.

Recruiters cajoled their audience not to wait, but most young men waited and weighed their options. Enlistments slowed down as June 5, the national day to register for the draft, came closer.

Then they learned that the Texas National Guard needed twelve thousand volunteers.