The effort to fill the ranks of the National Guard in Texas was in full swing by July 1917. Recruiting had begun in earnest by early June. Texas had to raise four new infantry regiments and other units such as artillery, medical and engineers from across the Lone Star State. In addition, Texas already had three infantry regiments plus many other units to maintain at full enlistment. It was a tall order for Texas. The National Guard would need twelve thousand new volunteers.

By the end of June, 1917, they had less than three thousand.

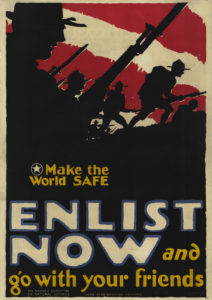

The Navy, Marines and the regular Army had been recruiting aggressively since before war was declared in April. And Texans had responded. News of the local National Guard units was made public just as men were preparing to register for a national draft on June 5th. Since then there had been rallies and parades and speeches. Recruiting offices opened in cities and large towns across the state. Prospective commanders were working overtime to persuade men to “avoid the draft” by enlisting in the Texas National Guard.

Northwest Texas

In northwest Texas and the Panhandle, there were fifteen recruiting offices for a new unit, the Seventh Texas Infantry regiment. The response to the recruiting drive had been very positive in some cities, but there was concern in Abilene, Decatur, Gainesville and Fort Worth.

Something had to be done. The governor announced that the week of July 4th would be Texas Enlistment Week and exhorted patriotic organizations and community leaders to, once again, make the case for serving in a Texas outfit with neighbors.

Members of the Adjutant General’s staff in Austin were getting nervous. Washington had decided to cap the number of National Guardsmen soon in anticipation of a nationwide draft. Drafting a new army to fight in Europe was less disruptive of the kind of greater war effort that Washington was planning. If Texas was going to have a distinct force to fight in the Great War, now was its chance.

As the drawing of America’s first draft numbers since the Civil War approached, the National Guard got a reprieve: states would be able to recruit their National Guard units until at least early August. For some recruiters, it would go right down to the wire.

By early August, 1917, 14,057 men had been added to the Texas National Guard.

Amarillo

Otho K. Farrell had been busy. Since moving back to Amarillo from Waynoka, Oklahoma in the fall of 1914 he had been going to school in his spare time at Draughon’s Business College. The rest of his time went to the Santa Fe Railroad. Now that Otho was learning stenography, bookkeeping and typing in school, he was also moving up at the Amarillo headquarters. By 1917 Otho was a stenographer in the Superintendent’s Office.

It’s hard to know what O.K. Farrell thought of the war in Europe. He was still keeping in touch with his sister’s classmate back home, Gladys Loper. And by the summer of ’17 he had been in Amarillo for two and a half years. Otho did not seem to be an adventurer or a crusader. So one can imagine his parents’ surprise when he wrote to them in Waynoka with news that he had enlisted in the Texas National Guard and was going to be a soldier.

O.K. Farrell was still twenty years old. He wasn’t yet old enough to register for the draft.

July 1917

Early on July 9th, 1917, San Francisco Bay was rocked when a barge loaded with four million pounds of gunpowder exploded at Mare Island Naval Shipyard. The explosion was so large a concussion wave knocked people down miles away. Six people were killed. The similarity of the disaster to the Black Tom explosion in New York Harbor just a year before caused many to speculate about a ring of saboteurs.

(Learn more about the Mare Island explosion here.)