On May 17, 1917, T.A. Hickey made his way to the Post Office in Brandenburg, a tiny settlement about halfway between Fort Worth and Lubbock, Texas. Hickey, a radical socialist, was editor of the Socialist Party of Texas’ official newspaper, The Rebel. He had sixty pages to send to the paper, which was published in Hallettsville in southeast Texas. Each edition of The Rebel carried the slogan, “The great appear great to us only because we are on our knees. Let us arise.”

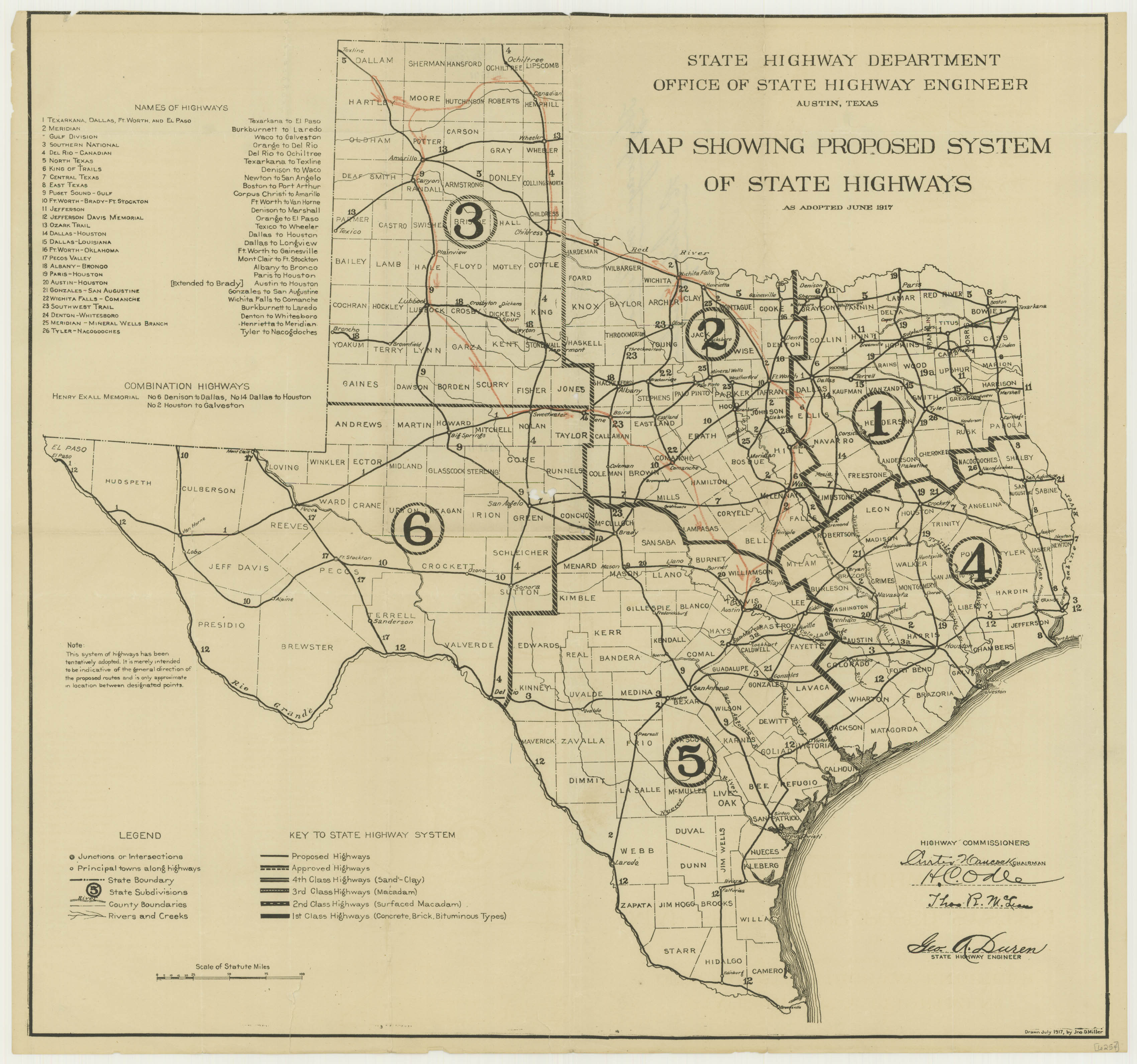

As Hickey approached the Post Office in Brandenburg (now called Old Glory), he was approached by four men who motioned toward a waiting car. According to Hickey, leading them was a Texas Ranger named John Montgomery, distinguishable by his one arm. Montgomery took Hickey’s writings and told him to “climb in”. He asked Montgomery to show a warrant but was told a warrant wasn’t needed. As Hickey would later put it: “Under the persuasion of the guns I got into the automobile and was conveyed at the rate of thirty-two miles an hour to Anson.”

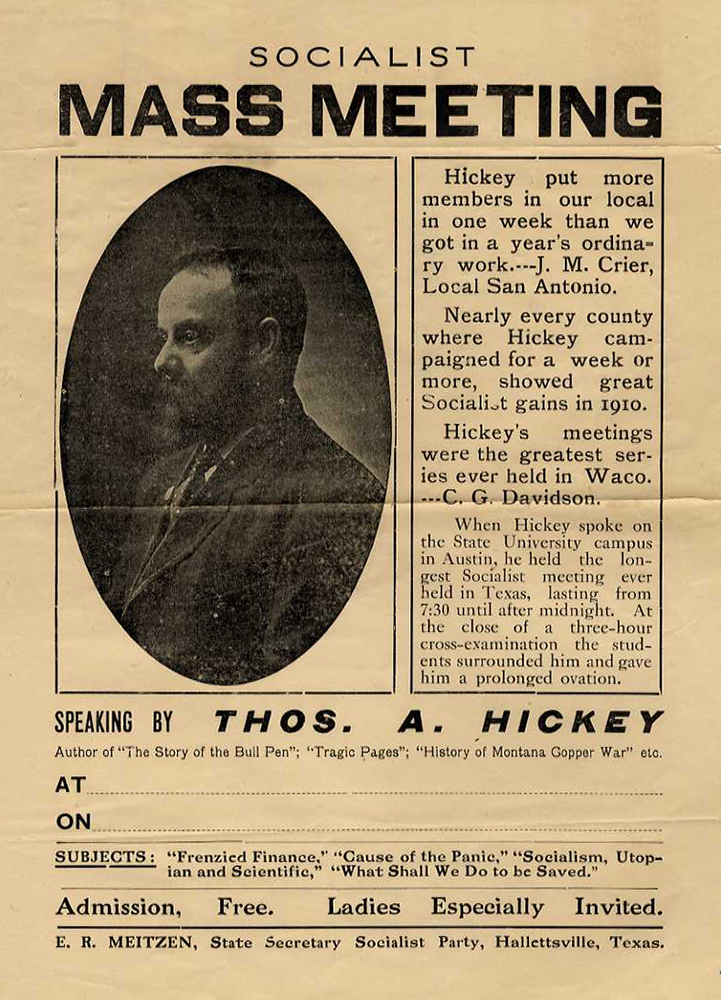

Labor organizer

Thomas A. Hickey was born in Dublin, Ireland. In 1892 he emigrated to the United States, aged twenty-three. He stayed Brooklyn and joined the Knights of Labor, leading a strike there. Ten years later finds Hickey organizing lumberjacks in the Pacific Northwest. After that, he moved to Arizona where he was an organizer for the Western Federation of Miners. He was also the editor of The Globe (Arizona) Miner.

By the time Hickey made his way to Texas in 1905, he had been personal secretary to Socialist Party leader Eugene Debs and was a party organizer. He was also co-founder of what eventually became the I.W.W. (Industrial Workers of the World).

Editor of The Rebel, Socialist Party Weekly

Hickey had organized industrial workers, lumberjacks and miners. In Texas he took up the plight of the farmer. Texas farmers were increasingly farming land they didn’t own. By 1910, over half (53.3%) were tenant farmers working for absentee landowners. Tenants usually were kept on the farm by debt to the owner. In their desperate situation, Hickey’s message was music to their ears.

By 1911 Hickey edited The Rebel, the Socialist Party weekly. His rhetorical flair on the page was matched with fire in his stump speeches for the cause. The Rebel boasted a circulation of 40,000 at its height. Its success briefly fostered other socialist papers in Texas.

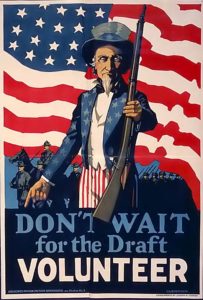

No topic was taboo to Hickey. He took on everything from Texas landowners to the Romanovs of Russia. He criticized President Wilson as the nation moved closer to war with Germany. As a socialist, Hickey viewed the European war as a conspiracy of plutocrats. He viewed the draft, in America and in his native Ireland, as another form of alienated labor. Likewise, he called on politicians and industrialists to pick up a rifle and serve first. Hickey reported on the annual meeting of the Farmers’ and Laborers’ Protective Association in nearby Cisco just before his arrest.

Following his arrest, Hickey was driven 37 miles to Anson, Texas where he was placed in custody of the Jones County sheriff. After an hour and a half, he was driven to nearby Abilene, where he was placed in Federal custody. When he secured legal counsel, Hickey was released on $1,000 bail nearly three days after his arrest. Hickey left with a summons to appear before a federal grand jury in Abilene on October 1, 1917. He never got back his documents.

Espionage Act

In Washington, Congress had been working since early 1916 on a law to counter espionage and other activities against the war by foreign agents in America. A year later, the Espionage Act was ready for President Wilson’s signature. In addition, the Espionage Act made it a crime to distribute in print items deemed by the United States to be false or detrimental to the war effort.

Just before the Espionage Act was to take effect, Postmaster of the United States Albert S. Burleson denied distribution of The Rebel through the mail. This effectively killed the paper. Reasons for censorship were not given, but The Rebel consistently encouraged its readers not to buy War Bonds and reported on efforts to resist the draft. The Rebel was the first publication suppressed under the Espionage Act of 1917. More would follow.

Thomas A. Hickey would keep his date with the federal grand jury in Abilene and, according to him, seven more grand jury appearances. He was never prosecuted. Apparently his involvement with the farmers’ rights group Renter’s Union was confused by the authorities with the FLPA. The Rebel never reappeared (you can read more about T.A. Hickey here).

The Espionage Act of 1917 is still very much in effect.