Woodrow Wilson’s ambition was not merely the United States win the Great War, but to win the role to make the peace after the war. To do this America would have to mobilize as it had never done before. It would have to build a citizen army the size of the other allies.

Universal male conscription was part of life in Europe, even in democracies such as France. Men were expected to serve as citizen soldiers part-time from age eighteen through their early forties. Over there, submitting to the draft was a part of upstanding citizenship. Wilson at first believed that volunteers would provide the men needed to fill out the Army. But no stampede to the recruiting station took place after April 6th. 73,000 men had volunteered for the U.S. Armed Forces in the six weeks following the declaration of war with Germany.

Decision to Draft

Wilson needed a national plan to build an army to fight in Europe. To do this he turned to the War Department, which crafted a plan for a draft. There had been a draft in the latter half of the Civil War in both the Union and Confederate States. It was unpopular then, being seen as unfair and easily gamed. Military service in the healthy economy of 1917 was not much more popular.

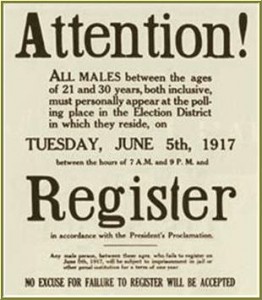

The plan was ambitious and far-reaching, as was the Army captain at the War Department who wrote it (Read about Hugh S. Johnson here). It called for all able bodied men between the age of 21 and 30 to register for the draft. Registrations would be taken by local draft boards that approximated voting districts, over four thousand of them. This draft was harder to game, it included legal residents as well as citizens of the United States. You could not buy your way out of the draft.

Congress debates

The plan went to Congress. While it was clear that the war required a huge army and needed it fast, drafting it was going to be complicated. That was because America had become complicated. A large part, about fourteen percent, of the U.S. population in 1917 was born elsewhere. Many more native-born Americans were born to immigrants. Many of them were from Germany or nations within the Austrian or Ottoman empires, now at war with the United States.

While America was rapidly becoming the world’s leading industrial nation, it depended upon agriculture as well. American workers were organizing and finding new power in the labor movement. There was a Socialist member of Congress. Many labor unionists felt the war pitted worker against worker. To them nationality mattered little when it was the same economic class getting shot on both sides of no man’s land.

Forging an Army

Congress had to consider all of these factors and more as they debated the Selective Service Act of 1917. Shall it send factory workers or farmers? Foreign or native born? Must you agree with the war to fight in it? From where in the United States will this Army come? Ultimately, to what America will it return? (A summary of the act and its impact is here)

Congress initially passed the Selective Service Act one hundred years ago, on April 28, 1917. Its goal was to draft one million men, although the reality of the war showed that even an army that size was not sufficient. Creating a new army would go on to effect every part of America. The war brought a shared experience to a wide band of its diverse but militarily untested manhood, the Americans.

All men between the ages of 21 and 30 were called to register for the draft on June 5th, 1917.