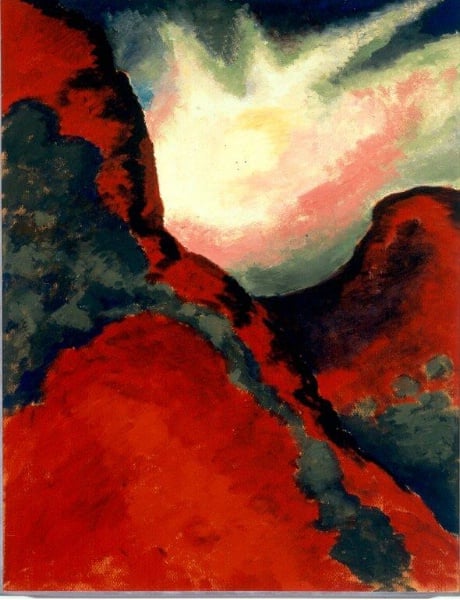

“It is absurd the way I love this country,” twenty-nine year old Georgia O’Keeffe wrote to her friends back East. O’Keeffe headed the art department at West Texas State Normal College in Canyon, a small town south of Amarillo. She began teaching there in the fall of 1916, having taught art in Amarillo schools from 1912 to 1914. O’Keeffe found her artistic vision during her time there, as seen in her watercolors of Palo Duro Canyon. “I belonged. That was my country” she would later write, “–terrible winds and a wonderful emptiness.” And the sky: O’Keeffe was transfixed by the big sky. (More about O’Keeffe’s Texas stay here)

The region

North Texas and the Texas Panhandle were younger and fast growing parts of the Lone Star State in 1917. This region can be bounded by tracing Wichita Falls, Gainesville, Fort Worth, Cleburne, Abilene, Lubbock and Amarillo on the map. Fort Worth was the hub of this region with a population of about 95,000 in 1917. The other cities were much smaller, but each had been growing at triple-digit rates every decade since about 1890.

Settlers in this area were other Texans and people from the “border” states of Arkansas, Missouri and Tennessee. Immigrants from northwest and central Europe added to the influx. There were German, Swedish, Norwegian, Czech, Italian, Slovak and Polish enclaves in the area. Farmers and tradesmen moved to America with neighbors from the old country. The African-American population in northwest Texas was about seven percent.

The work

Ranching dominated the Panhandle, along with agriculture. Farming and dairy production were more common than ranching in northwest Texas. More and more land fell under the plow in the ‘teens; up to 25 million acres statewide. Northwest Texas produced little cotton; the Panhandle produced none. Major crops were corn and wheat.

Infrastructure was also a major growth industry of 1910’s Texas. Rails and roads could not keep up with the population and their fascination with machines. Railroads such as the Missouri-Kansas-Texas (The Katy) and the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe reached deeper into Texas. Farms in the second decade of the Twentieth Century were becoming mechanized. Likewise, young men on the Plains were growing up with this new technology.

Oil was discovered in the Panhandle in 1910. More oil was discovered in northwest Texas in 1911. The development of oil fields in Texas created a boom economy, eventually making fossil fuels the state’s largest industry.

War comes to Texas

When war came, the region erupted in parades, rallies and other demonstrations of patriotism. Young men filed out of high schools and colleges, marching in rows to the cheers of onlookers. Bands played and local politicians held forth. Older veterans put on their gray uniforms, though some bravely wore blue. The feeling was of widespread support for the nation and for the war.

However, the enthusiasm also revealed lack of unanimity about the war. Not everyone was excited about joining a conflict that had roiled all Europe with no end in sight. Particular among these were the Europeans, German and other immigrants who may have been better informed about the war.

There was also suspicion of enemy activity in northwest Texas. The Amarillo Daily News reported of German spies in the city. Shots were fired at suspected saboteurs on a railroad bridge near Abilene. Moreover, arrests of enemy aliens were ordered in Wichita Falls by the U.S. Marshal there, but none were made. Most spectacular was the report of a dozen German agents being rounded up in El Paso. However, others reportedly slipped through the dragnet and over the Rio Grande into Mexico.

Meanwhile, in Washington on May 10th, Major General John J. Pershing was appointed commander of the American Expeditionary Force.