The effort to build a national army of volunteers and draftees was the mission of the War Department, but it was not the only one. This army had to be housed, fed, trained and equipped. It also had to be led by officers. Plans for creating this new army were underway even before war was declared in April 1917. From the start, enlarging the National Guard, and bringing it into federal service, was part of the plan. And the plan included the Texas National Guard.

Texas’ National Guard was about to triple in size. Three infantry regiments, a squadron (battalion) of cavalry, along with other units already served Texas along the Mexican border in 1916-1917. Four more infantry regiments would now be recruited, plus artillery, signal, engineer, supply and medical units. As a result, Texas was about to have a force of a size not seen since the Confederacy.

Recruiting the Guard

Recruiting this force along with the Army, Navy and Marines was going to be a monumental task. The federal draft, for which eligible men registered beginning June 5th, was about to draw its first names in July. By that time, nearly one million Texans had registered. Draftees who passed their physical would normally be inducted into the Army.

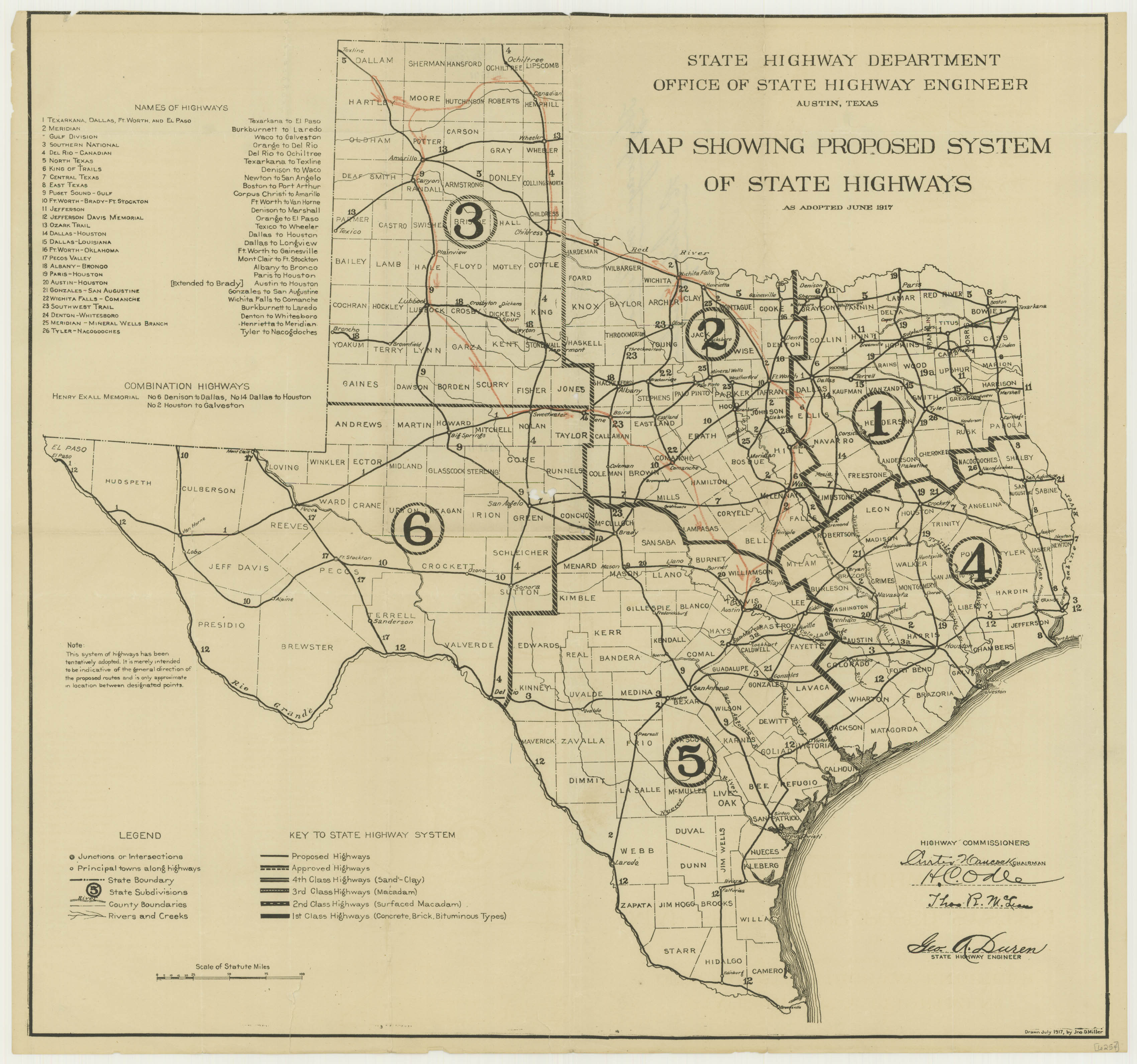

Northwest Texas and the Panhandle was the home of one of the new infantry regiments, the Seventh Texas. The part of Texas that was home to the Seventh can be seen below, roughly in sections 2 and 3 on the map. It included Amarillo, Lubbock, Abilene, Fort Worth, Wichita Falls and the surrounding areas.

Like the other three new regiments, the Seventh had to recruit fifteen companies of 150 enlisted men each. The job of recruiting was given to the prospective commanders of the fifteen companies. The companies would each draw from one of the larger county seats in this area of Texas. Most commanders recruited in their hometowns. Because of this, they would have to use their connections, their wits, and not a little of their own money to reach one hundred and fifty men.

Advantages to volunteers

Getting men to volunteer for the Texas National Guard, while the branches of the federal Armed Services were also recruiting required organization, persuasion and skill. Also recruiters were not permitted to disparage the other services. Recruiters couldn’t hide the fact that Guardsmen probably would fight overseas. Even so, men between the ages of eighteen and forty-five could consider the advantages of volunteering for the Guard.

First of all, the pay in the Guard was the same as in the Army: $30 a month for privates when serving overseas. Just as persuasive was the fact that Guardsmen shared a place and a sense of community. A Cleburne newspaper editorial exhorted young men to “soldier with the boys you know”. And the leaders they knew: officers were also local businessmen, lawyers and educators.

Another advantage was the support a company would get from its home community. Each of the communities that was home to a National Guard unit drew great pride from the example of their fighting men. In addition, the men of the Seventh would have to rely on their hospitality in the early days.

Spreading the word in north Texas

Texas National Guard officers were busy recruiting for the Seventh Infantry soon after registration opened for the draft. Captain Thomas Barton had opened a recruiting office in Amarillo by June 16th, telling a reporter, “we will go and return as an Amarillo Company”. Other offices opened in Childress, Cleburne, Gainesville, Denton, Wichita Falls, Decatur, Abilene, Lubbock, Vernon, Crowell, Quanah, Clarendon and two offices in Fort Worth.

Local newspapers, Chambers of Commerce and mayors helped the cause. Another parade was held in Amarillo. Denton had a recruiting rally, as did Gainesville, Cleburne and Vernon. In late June, three thousand reportedly attended a rally in Abilene. Decatur’s rally lasted three days.

Recruiting officers and civic leaders were working under pressure. Draftees would be called up for their physicals beginning on July 20th. Initially they believed that recruitment for the National Guard would stop on that date. To them it was a matter of pride for local men, with local officers, to represent Texas in the World War. Consequently, Judge J.M. Wagstaff exhorted the three thousand gathered in Abilene in June, “If you haven’t enlisted, why? Are you less patriotic than the men of 1861? Why can’t the boys of Abilene and Taylor county serve their country?”