In 1915 half of all Americans lived in rural areas. When World War I broke out in 1914, the United States was in recession. The war in Europe eventually boosted the American economy, but the life of a farmer was a tough one for a lot of reasons. This was at a time when over 30% of American workers were in agriculture. Today, it is less than one percent.

1915

1915 was a fateful year for many in northwest Texas and in Oklahoma. As in other places in the American South and West, poverty on the farm was a fact of life. In Oklahoma as in Texas, over half the farmers worked land they didn’t own. What they earned from selling crops was quickly eaten away by the owner’s share; by rent and by debt. Tenant farmers were kept on the farm by revolving debt at rates that started at around ten percent and could go as high as 100% for some loans.

The war in Europe closed overseas markets and sent prices down, especially for cotton. Land prices also fell, resulting in foreclosures and higher rents. Tenant farmers learned to beware the landowner, the lender and the buyer in town and to stay in their good graces.

In 1915, the solution for many in these dire straits was radical socialism. The most radical organization, International Workers of the World, did not admit farmers as they were nominally self-employed. Consequently, that year the Working Class Union came to Oklahoma. The WCU was like the IWW in many respects, and they admitted farmers. It was active in western Louisiana, Arkansas and east Texas, but the lion’s share of its membership lived in southeast Oklahoma.

The WCU

The Working Class Union, like the FLPA in Texas, functioned as a mutual aid society for tenant farmers. Activist lawyers in the union brought farmers relief from illegally high bank rates and saved some from eviction. But the WCU also advocated for abolishing “rent, interest and profit-taking” and members were not above using some muscle to get their point across.

Participation in the WCU dropped in Oklahoma from a reported 20,000 members after cotton prices rebounded in 1916. However interest in the union grew as it became clear there would be war with Germany in 1917. Activity increased in all the radical groups, and membership in the Working Class Union apparently doubled in the months leading up to August 1917.

The sentiment among many in rural Oklahoma, and in many parts of rural America, was anti-war. Part of this was motivated by the ideology of a “rich man’s war, poor man’s fight”. Part of it was a lack of interest in war and absence of malice against Germans. Above all, many were motivated by fear of an overseas war that was claiming millions of lives each year.

August 1917

What happened next has been a subject of debate for a century. Young men who registered for the draft were ordered to report for their physical beginning on July 20, 1917. However, men who hoped to dodge the draft (“slackers” was the contemporary term) were congregating in groups in rural areas; and they had help. Radical socialists, including members of the Working Class Union, harbored draft dodgers and those who had a change of heart since registration day.

WCU organizers had circulated through southeastern Oklahoma, calling for resistance to the draft and to the war. Now they were making the case that the time had come for resistance by force. On August 2nd, when the Seminole county sheriff and his deputies rode into the country to arrest draft dodgers, they were fired upon. One deputy was wounded.

Bands of armed radicals gathered in four counties in southeastern Oklahoma that day. A number of them met at the farm of John Spears, who’d raised the red flag of revolution on his farm in Sasakwa in Seminole county. The crowd at Spears’ Bluff and others nearby spread out that night, burning railroad bridges, climbing poles and cutting wires.

In the moment, these rioting bands of farmers, mechanics and laborers believed they could do more. They had heard rumors of a more general uprising. To hear it told after the fact, these radicals resolved to march on Washington D.C. to stop the draft and end the war.

Reaction

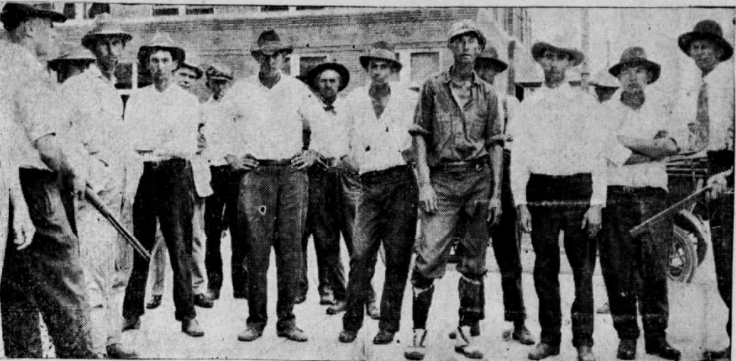

In the meantime, news of the violence had mobilized posses who turned out in force. There were confrontations; gunfire was exchanged. But the rebellion broke and most men put down their arms instead of firing on their neighbors. Others fled in small groups. Four men were shot dead. About four hundred fifty were arrested in the chaos. Meanwhile, local Native Americans had just celebrated their New Year, the Ceremony of the Green Corn. The incident now had a name.

Whether the Green Corn Rebellion was resistance to the draft or the aborted overthrow of the United States government is still debated. The fact is that it was the bloodiest antiwar riot of the era, but not the only one. 184 of the rioters were brought to trial and one hundred fifty received prison sentences. The Working Class Union, and other Socialist organizations not involved in the incident, were forced to close up shop (more on the Green Corn Rebellion here).