During the summer of 1917 the U.S. Army built nineteen training camps for its National Guard divisions. It was an enormous task: More camps were being built at the same time across the country to build a military essentially from scratch.

Because most of the National Guard camps were built in the South and West, and because the training was anticipated to be brief, soldiers were housed in canvas tents intended for eight men.

That was the plan, anyway.

If you have ever spent a winter on the Plains, you know about wind. The cold winds that barrel south from Canada are called Northers, and in Texas they are serious business. A Norther can rapidly drop temperatures even on warm sunny days. The sky turns dark blue, the wind begins to howl, and then you– one observer was inspired to quote Milton–

“…feel by turns the bitter change

Of fierce extremes, extremes by change more fierce,

From beds of raging fire to starve in ice.”

John Milton; Paradise Lost, Book II, Lines 598-600

Cold Weather Arrives

Military planners did not expect the weather would deteriorate in the early fall of 1917; but Camp Bowie saw its first Blue Norther on September 26th. Soldiers had just recently arrived there from all parts of the Southwest, including posts on the Mexican border. The base was completely unprepared and, to make matters worse, lack of shelter meant that soldiers were living up to twelve to a tent.

Efforts were made to better prepare the men, but so far their standard issue was cotton summer uniforms and two wool blankets per man. The canvas tents had no walls, no heat and earth for a floor.

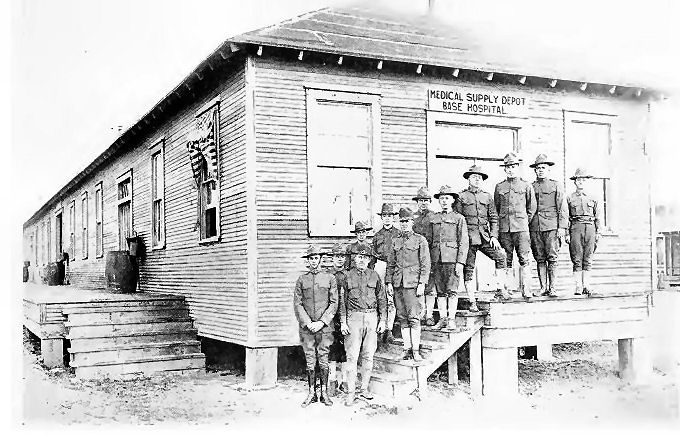

The second cold wind blew through camp on October 8th and found the camp little prepared. Construction on the base hospital had begun late in the game, opening its doors on September 24. It would not be complete until 1918. Some tents were issued small wood-burning stoves, others not.

The result of this was that the men started to get sick. Lack of warm clothing and heat plus overcrowding in the tents led to the spread of disease. Plainsmen who grew up without exposure to chicken pox, mumps and measles were now exposed. Soldiers from south Texas were not physically ready for the cold weather.

The unfinished base hospital was filling up. Normal occupancy for the hospital was set at 800 patients, with a maximum of 1,000. Soldiers were coming down with meningitis, measles, tuberculosis and pneumonia. It was not uncommon for a soldier admitted with measles to get sick with pneumonia after a few days. Men were starting to die.

Camp Under Siege

Sickness raged through Camp Bowie in October and November of 1917. By early November the hospital held 1,867 men, over twice the normal capacity. In November forty-one men died from pneumonia alone. Thousands were admitted to the hospital during the epidemic. Training for the war was halted because of it.

Response to the crisis was piecemeal. Winter clothing arrived in October and November, but wool overcoats and extra blankets did not arrive until early December. Small stoves for the tents were provided, with wood to burn. More tents were erected, easing overcrowding. Soldiers began to install wooden walls and floors to their tents to protect themselves from the weather.

A quarantine at Camp Bowie was necessary. Passes were revoked and soldiers were kept in camp to prevent the spread of disease. Soldiers newly transferred to Camp Bowie were kept in a separate observation camp for two weeks before entry into the base. Doctors and hospital staff were increased, and hospital construction was accelerated.

By December over 3,300 soldiers had been admitted to the base hospital with measles and pneumonia. On average, eight men died each day. Companies could not function for all the men on the sick list. When the Surgeon General of the Army inspected Camp Bowie in early December, he remarked that the situation there was worse than in any of the other training camps he had seen. Twenty-five men died during the General’s brief visit.

Camp Bowie fights back

On December 10 more blankets and wool overcoats arrived. The Army hastened to add plumbing and facilities to the hospital complex under construction. 2,300 tents arrived as well as 1,200 stoves. Donations from the Red Cross and towns all over Texas and Oklahoma began to arrive. Every man had at least four blankets.

A week later, the hospital still had 1,427 patients, well above maximum capacity. The cold weather continued into January 1918 with temperatures near zero and blizzard conditions on the 10th. January 22nd set a record low at 6 degrees with more snow. Camp Bowie experienced an outbreak of mumps that month. At the hospital, there were still deaths every day.

But the sick rate was declining. While the weather at Camp Bowie was nothing like the Army imagined when Fort Worth was chosen, men were adapting. Better accommodation (well, the men were still sleeping under canvas in winter) and warm clothing made it easier to avoid disease. Watching new arrivals in a separate camp also helped. Probably the best action was the decision by commanders to furlough nearly the whole camp for Christmas.

Camp Bowie’s hospital was finally completed by February, 1918. That’s when the last of the plumbing was installed in the over fifty buildings that made the hospital complex. By mid-April, the hospital census had returned to normal.

234 men died at Camp Bowie of pneumonia in 1917 alone.