On July 2, 1918 the 36th Division received its orders for transport to the Port of Embarkation on the East Coast. The first group of soldiers left on July 4th. The division had practiced for this moment, and now it was here.

But how do you buy cross-country train tickets for 28,000 men?

To move the men and the raw materials of war where they needed to go, the U.S. Government took control of American railroads in December 1917. The U.S. Railroad Administration was created by law early in 1918 to coordinate rail traffic for the next two years. Similarly the movement of troops across the country was the responsibility of the Inland Transportation Division and it had priority in scheduling rail travel. (Read more about the Federal Possession and Control Act here.)

All Aboard

July 1918 turned out to be the biggest effort by the Inland Transportation Division in the entire war. The United States had been transporting soldiers and marines to France for a year already, but now more men were trained and ready for deployment.

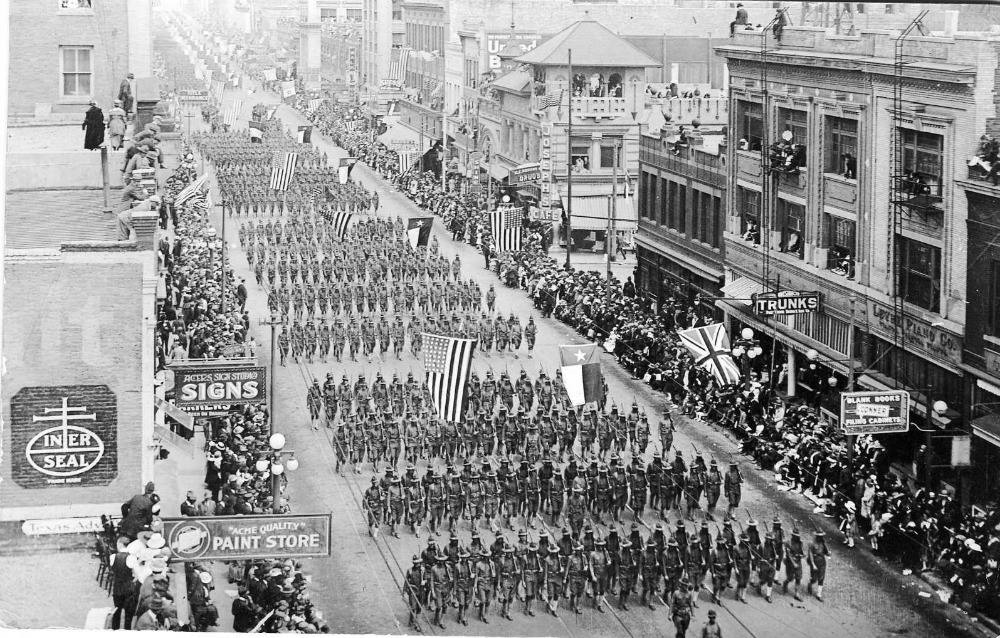

Units of the 36th Infantry began to leave Camp Bowie in Fort Worth in early July. The trip across the country took at least four days, although it depended on which route was taken. Some trains traveled east through Shreveport, Birmingham, Vicksburg, Atlanta, Raleigh, Richmond, Washington and Baltimore to Jersey City.

Other trains went north through Arkansas to St. Louis and then east through Cleveland, then Scranton to Jersey City. Some trains even traveled to Detroit and then by ferry into Canada, reentering the U.S. in Niagara Falls. In any event, much of the 36th Infantry Division was somewhere on the rails on July 13, when the Inland Transportation Division moved 41,000 men on 77 dedicated troop trains through the country. The busiest day on the rails of the war.

Getting this many men transported was a complex and delicate task. Unfortunately there were mishaps. Seventeen miles from Shreveport, four cars on a train carrying 36th Infantry soldiers derailed injuring several men and killing one.

Seeing America

After months of training in Camp Bowie and enduring the daily grind of duties, the men of the 36th all seem to remember vividly their voyage across America. The first day covered familiar ground, the Great Plains. After that the scenery changed, and depending on what train one was on, a soldier saw vast cornfields and Midwestern cities. In contrast, he may see remote Southern hamlets between the bright cities of Birmingham and Atlanta. They saw factories and forges, tenements and some of the industrial wonders of the time.

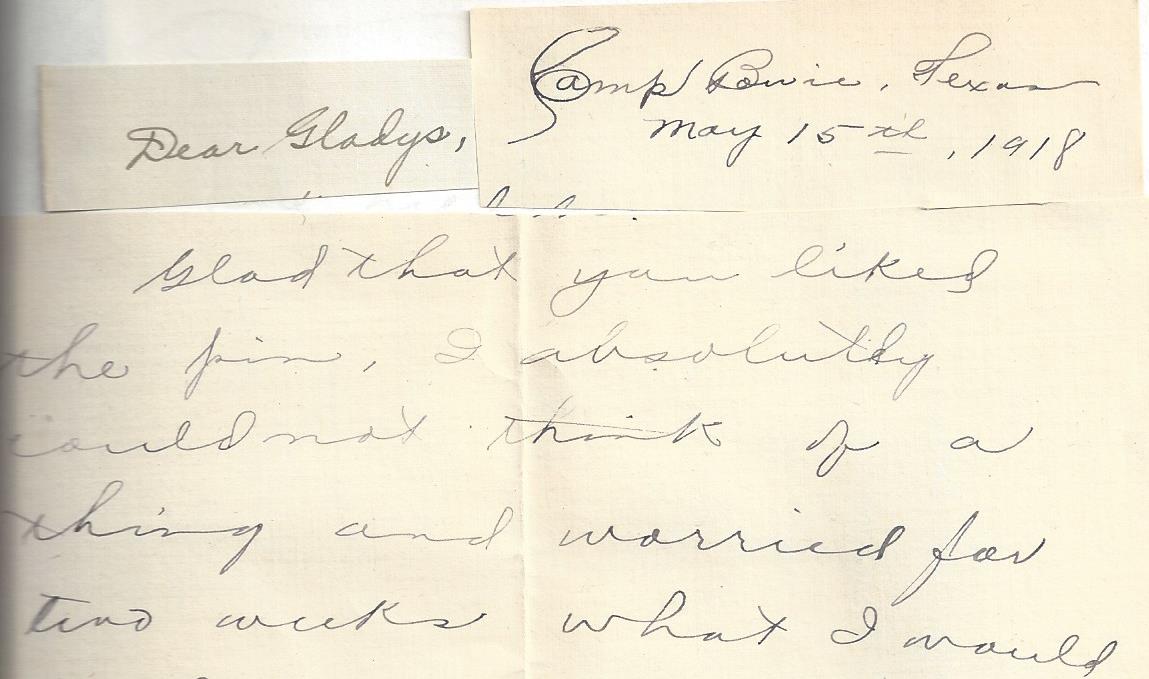

What none of the men forgot was the welcome. Everywhere they went, if the train had a reason to stop, there was a crowd. Young women in American Red Cross uniforms gave out candy and postcards, and sometimes kisses. Mail was handed out of rail car windows, and it was posted. Bands played on station platforms. Men marched off to meals, to baths, or even a swim in Lake Erie. Addresses were exchanged and letters actually sent back and forth from France. People gathered and cheered in small towns, even if the trains didn’t stop.

America showed up; and it was seen from train windows by men going off to war.

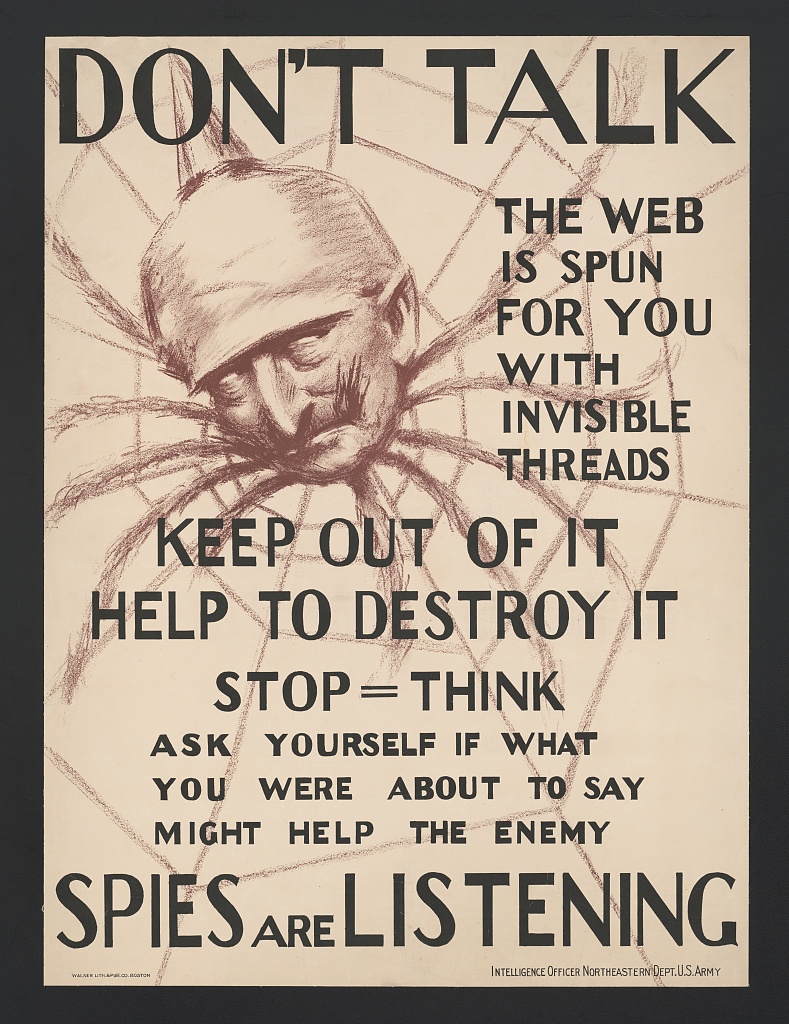

Defend This

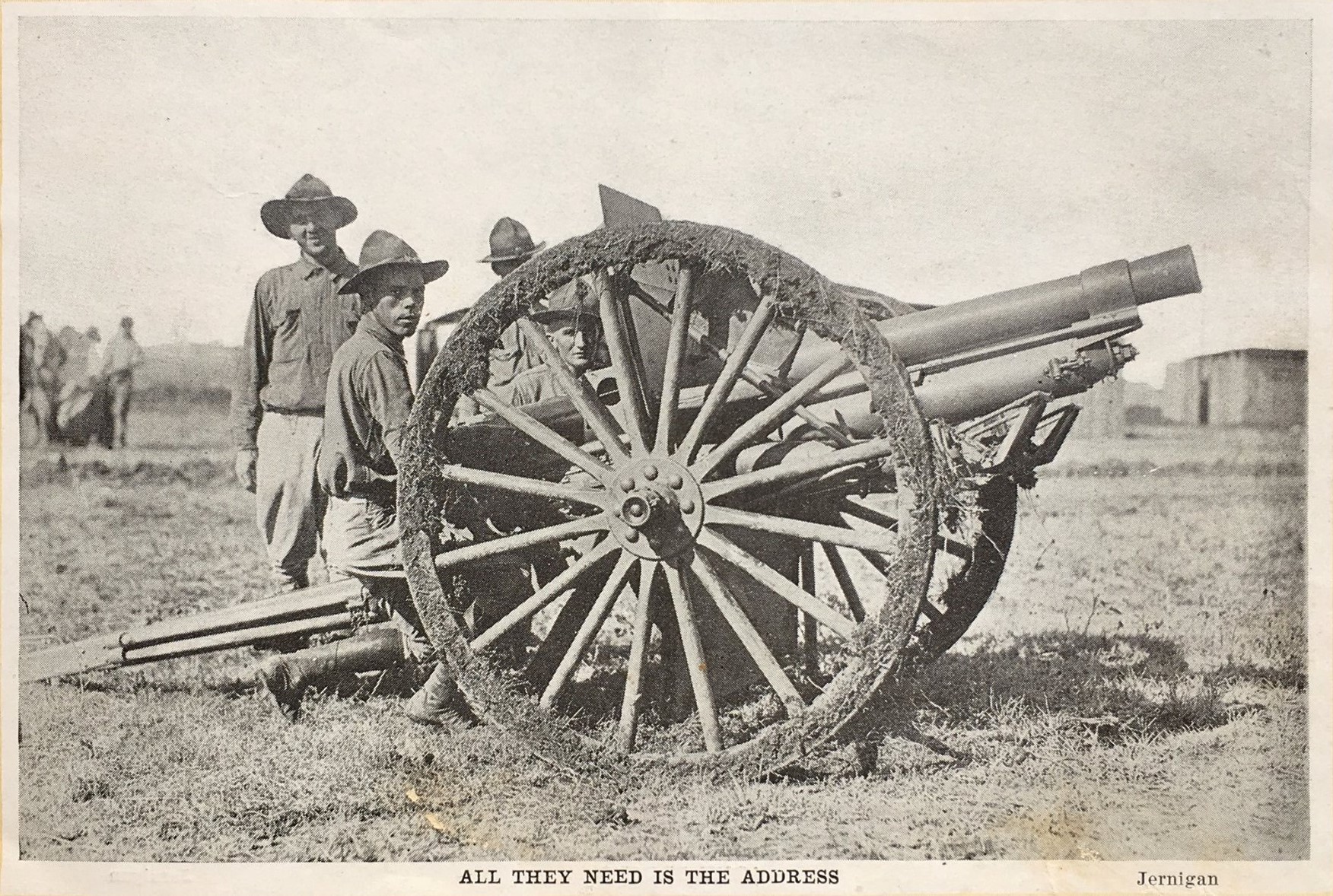

Whatever lay ahead for these men, the memory of their sendoff meant a great deal that summer of 1918. One private in the 61st Artillery Brigade, 36th Infantry Division remembered their encounter this way:

“The men felt grateful as well as pleased over the manner in which the American people along their route had greeted them, and many a man felt that he had really been appreciated for the first time in his life while on this trip, and since he was making a great sacrifice and had been torn by the emotions of leaving home and everything he considered dear, these manifestations had touched him more than they ordinarily would have done.”