Corporal Otho Farrell left Camp Bowie on July 11, 1918 with Headquarters Company, 142nd Infantry. Being a railroad man, Otho kept a diary of their progress across the country.

Headquarters Company stopped in nearby Fort Worth on the eleventh, the next morning in Malvern, Arkansas, before reaching Little Rock the afternoon of July 12. On the morning of July 13, they were in East Saint Louis reaching Indianapolis by evening. On the fourteenth, they arrived in Cleveland on their way to Buffalo, Rochester and finally Syracuse by 9 p.m.

After arriving in Jersey City at 8 a.m. on July 15, Headquarters Company was ferried past the Statue of Liberty to Long Island City, Queens. There they waited for the train to take them to Camp Mills, arriving at 5:30 p.m.

Camp Mills

Camp Mills was established in the summer of 1917 near Hempstead, Long Island as a temporary training camp for National Guard divisions. From August to October that year the 42nd Infantry Division received basic training there before embarkation to France. On April 4th, 1918, Camp Mills became part of the New York Port of Embarkation, a massive command that organized the transport of millions of Americans to the war in Europe.

Camp Mills, about ten miles from the dock in Queens, was large enough to house a division of troops. Like the other National Guard camps, the men lived in tents. Camp Mills had a hospital, all the facilities, and a garrison of fifty-five hundred.

Otho Farrell and Headquarters Company spent only two nights at Camp Mills, 15 and 16 July. Other members of the 36th Infantry Division stayed longer; the 61st Artillery Brigade was at Camp Mills for a week. Men of the 61st were able to get passes to New York City during their stay. However, soldiers of the 142nd Infantry were treated to a physical, uniform, and equipment inspections and were issued travel documents. Soldiers of the 36th Infantry who were not American citizens had the opportunity to become naturalized or else serve stateside.

Ships of the Army

Before the war the Army Transportation Service had the responsibility of moving modest forces and equipment to where they were needed in the Caribbean or across the Pacific. When war against Germany was declared in April, the Service had two troop transports on the Atlantic. With two million men entering the ranks that year, the Army was going to need a navy in 1917.

By June 1917 the Army Transportation Service was greatly enlarged and the New York Port of Embarkation was established. The Service brought on line a number of German, Austrian and–after March 1918–Dutch ships seized in American harbors as well as other ships leased to the Army. On June 14th, the Army embarked its first convoy of twelve thousand personnel aboard fourteen passenger vessels, plus U.S. Navy escorts. (Read more about the seizure of neutral Dutch vessels here)

In 1918 the New York Port of Embarkation command grew to include operations out of Philadelphia, Baltimore and Boston. In addition, it sent troops to be transported on its ships in Montreal, Halifax and St. John’s, Newfoundland. By then the Transportation Service had 173 ships of many nations in its fleet. Moreover, at the height of the fighting in the fall of 1918, the Army was embarking ten thousand men to France every day.

To the Docks

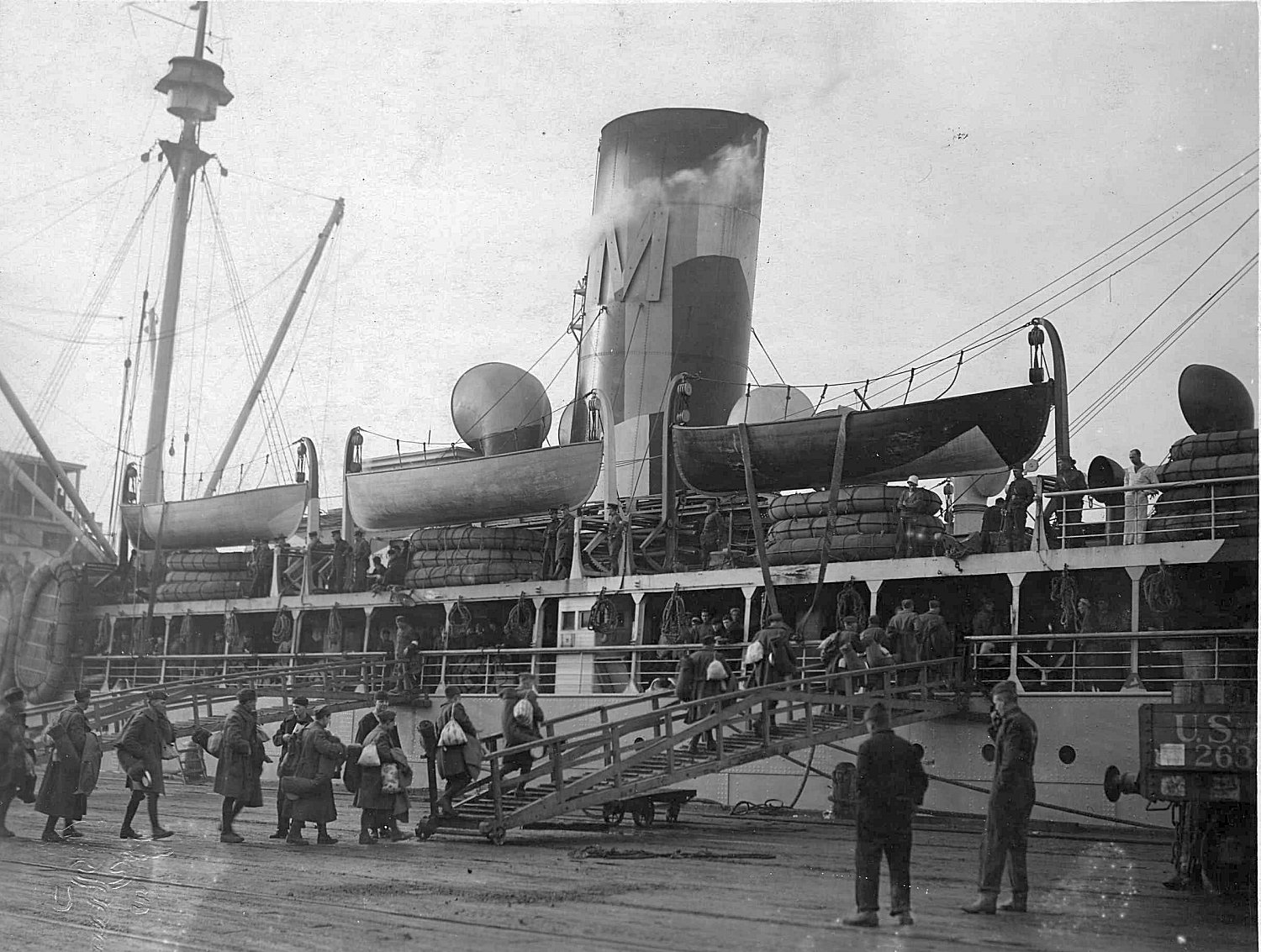

At 4:30 a.m. on July 17, 1918 Headquarters Company and the rest of the 142nd Infantry Regiment left Camp Mills by train for Long Island City. From there they took a ferry down the East River and up the Hudson to Hoboken, New Jersey, home of the Embarkation command.

The New York Port of Embarkation had taken over the port facilities of two German passenger lines for its operations. About twenty German and Austrian vessels, seized by the United States, were now transporting troops. The 36th Infantry Division boarded ship during the busiest days of the war for the Army Transportation Service. For example, the same day the 36th embarked it was joined by the 6th, 7th and 85th Infantry Divisions at Hoboken.

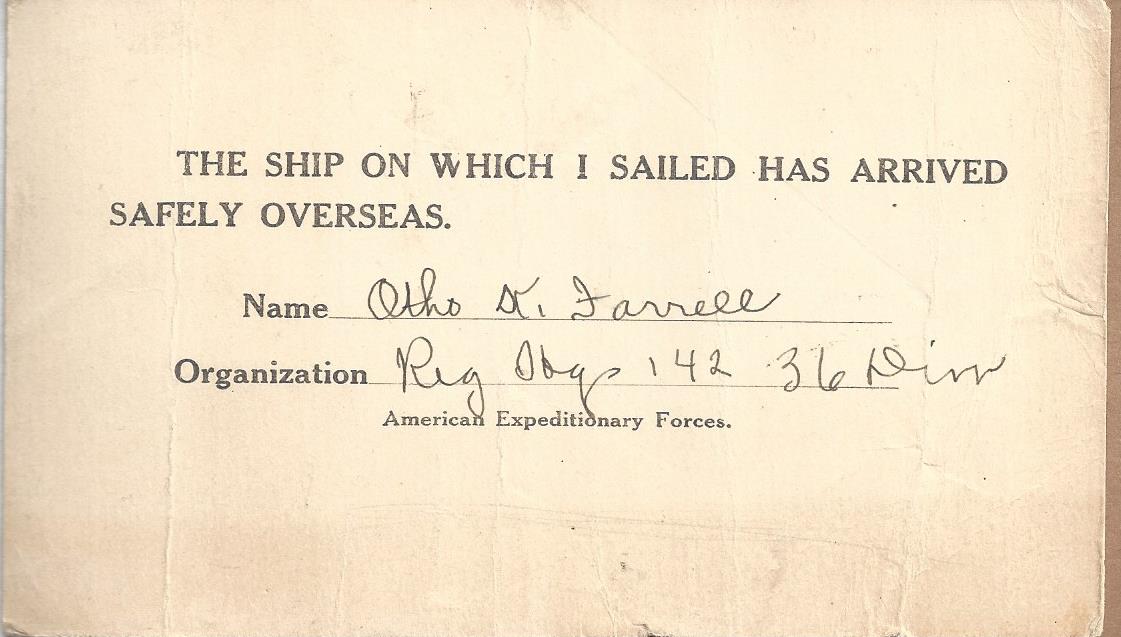

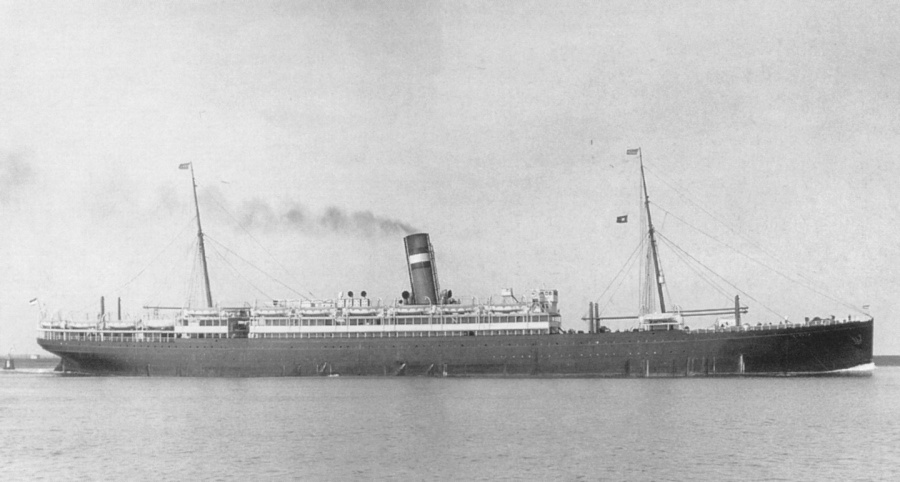

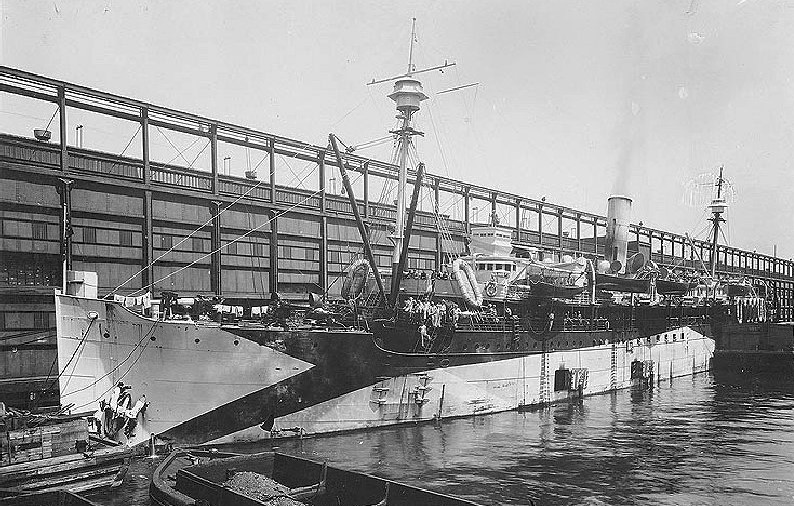

Otho Farrell and Headquarters Company arrived at Pier #2 in Hoboken at 8:30 a.m. They lined up in a large, dimly-lit building on the dock until they boarded ship an hour later. Headquarters Company, the Machine Gun Company, the Medical Detachment and the Supply Company all joined Second Battalion (Companies E, F, G and H) on the Rijndam. First Battalion (Companies A, B, C and D) boarded the Maui. Third Battalion (Companies I, K, L and M) traveled on the Lenape. Soldiers on the Maui found themselves stuck in port while it was repaired; and their departure was delayed two weeks.

Convoy sets sail

Although Otho Farrell was aboard the Rijndam by 9:30 a.m. on July 17, the convoy did not leave Hoboken until 2:25 p.m. the next day. There on the Hudson River thousands lined the shores to cheer one of the biggest convoys of the war on July 18. For the men of the 36th Division, it was a memorable event. Men lined the rails of their ship as they passed the skyscrapers of Manhattan, returning cheer for cheer. Lastly, a Navy band serenaded the convoy from Battery Park, finishing with The Star-Spangled Banner.

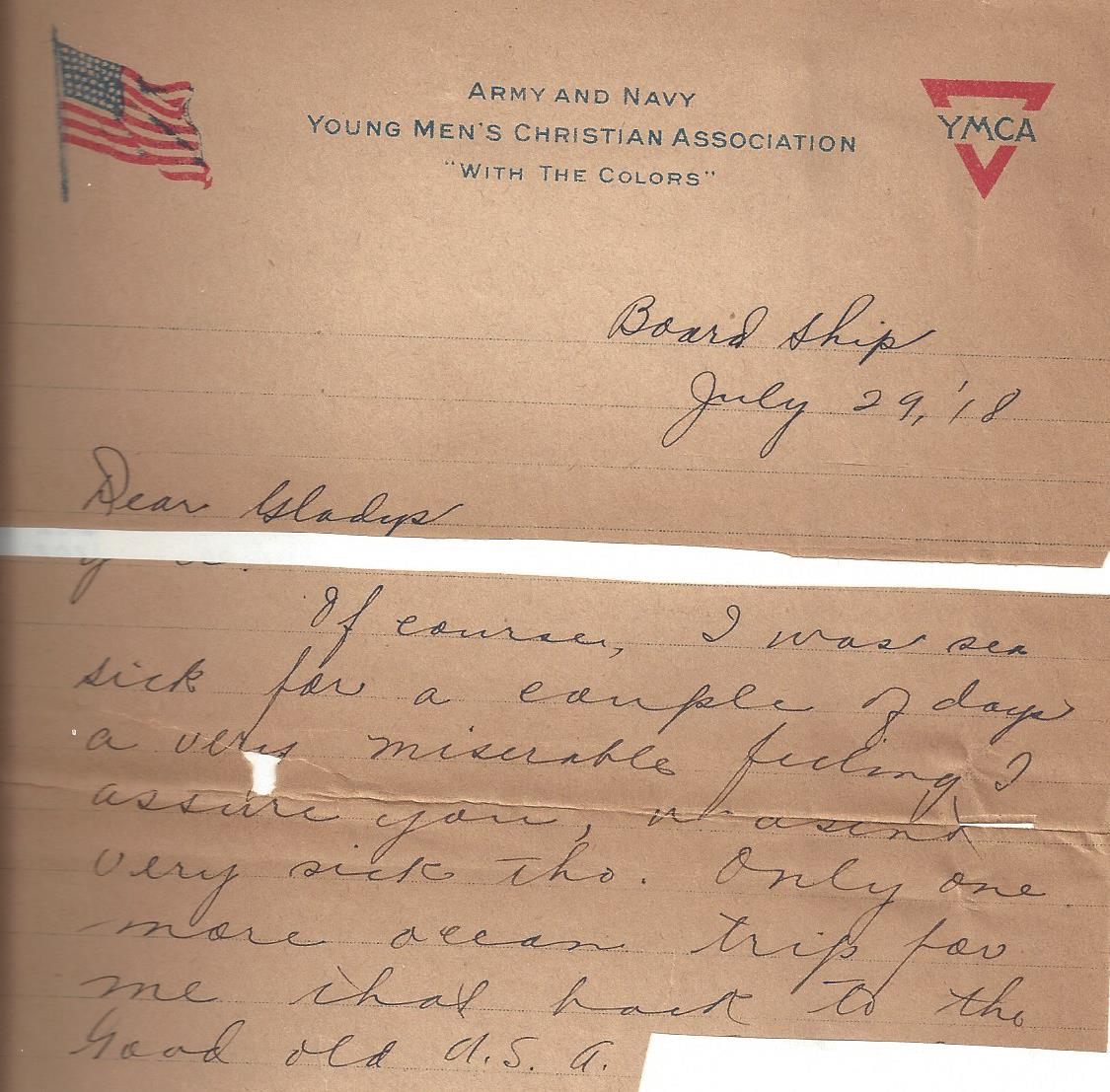

Most of the men from Texas and Oklahoma had never been on a ship, or had seen the ocean. Conditions aboard ship were very crowded. Apart from the frequent lifeboat drills, men had little to do but wait in line for meals. Not that many wanted to eat; the waves began to roll early in the voyage and most men were seasick. Otho Farrell wrote to his sweetheart Gladys Loper about his unpleasant ordeal.

While the food was unappetizing for most and the sea inhospitable, the men filled their time writing letters or watching silent movies in the mess. Some soldiers helped to move coal through the ship. Others watched the crews take gunnery practice at sea. Because of the threat of German submarines, there were always men up on deck watching.

“Periscope!”

After twelve days at sea with eleven other ships, the Maui was in convoy nearing France. Her convoy had left Hoboken on July 31 and the voyage had been unremarkable when a periscope popped up in the middle of the convoy on August 11, 1918. Captain Ben Chastaine of the 142nd Infantry was on deck: “The appearance of the undersea craft was the signal for every available piece of naval artillery to open fire…The guns, however, had not been able to get into action before the submarine had launched a torpedo which barely missed the stern of the Maui.”

Destroyers rushed to the scene and dropped depth charges. Transport ships fired their guns. By this point, the entire company of every ship was on deck in life jackets cheering the Navy as they fought back against the submarine. When one depth charge brought up an oil slick from below, the men aboard the Maui cheered like it was a fourth-quarter touchdown.