The 142nd Infantry Regiment left Camp Bowie in Fort Worth on the 9th, 10th and 11th of July, 1918. Early on July 17, the regiment was in Hoboken, NJ waiting to board ship. The next day, most of of the 142nd embarked for France (soldiers aboard one ship, the Maui, stayed behind while it was repaired). Much of the 36th Infantry Division, to which the 142nd Infantry belonged, convoyed from Hoboken on July 18. This convoy was joined by more ships from Newport News, VA which included most of the Division’s 143rd Infantry Regiment. The rest of the 36th Division embarked on July 26th, July 31 and August 3.

War at Sea

These troops, as well as the 6th, 7th and 85th Infantry Divisions crossed the ocean at a most busy and deadly time in the Atlantic war. German submarines sortied to sea to prevent a defeat on land should the American force land intact. On May 31, 1918 the troopship USS President Lincoln was returning from France with 715 aboard when it was torpedoed by the U-90. Twenty-six were killed and a Navy officer was taken prisoner (to learn more of this remarkable officer, Edouard Izac, click here). On July 1, the troopship USS Covington was torpedoed soon after leaving port in France. The Covington sank the next day, with a loss of six of the 776 on board. The loss of life on both ships would have been much greater if they were inbound to France and full of troops.

Just one day after many of the 36th Division sailed out of New York Bight, the cruiser USS San Diego struck a German mine off Fire Island, New York. The San Diego, on convoy escort duty due to its age, sank with a loss of six men and was the largest American warship sunk in the war. The mine was laid by the U-156 which caused even more trouble days later when it used its deck gun to fire on coal barges within sight of Orleans, Massachusetts.

In France

Units of the 36th Infantry Division reached port in several places. For example, most of the 142nd Infantry landed in St. Nazaire on July 30. St. Nazaire was first among the Atlantic ports used by the American Expeditionary Forces as a logistics center for men and materiél from the U.S. By the summer of 1918 it had been joined by the ports of Brest, Bordeaux and Cherbourg. Together these ports received two million American fighting men and millions of tons of war materiél over a two-year period.

As they had when sailing past New York, men on every ship lined the deck rail as they approached the old continent. They had heard and read much of France and the war, but now here it was, right in front of them. First impressions being important, the experience of each man as he stepped onto solid ground in France after an arduous journey would stay with him. Ships coming into these ports usually rode at anchor for one night and disembarked their troops early the next morning, often before breakfast. Hungry, tired and walking on wobbly legs, the men made their way through the winding streets of unfamiliar port towns to a temporary camp some distance outside town.

First Impressions

Whether the experience was positive depended on where your ship made port. The most positively received port of debarkation was Bordeaux. The old city lay 52 miles up the Gironde River from the coast, with much more temperate weather. Everywhere there were sights to behold, “the cathedrals, towers and art museums,” as one soldier wrote home. “The boys have to drag me out [of them] every time we go” into Bordeaux. The rest camp outside of Bordeaux was also fondly remembered.

St. Nazaire was the scene of an enthusiastic welcome as ships made their way up the Loire River. “All along the way French inhabitants rushed to the river bank and waved their hands and shouted,” one soldier remembered. While there, men from the 36th Division stayed at Camp No. 1, Base Section No. 1. There was nothing special about the accommodations in this massive American base.

Brest

The men who landed at Brest had a different impression altogether. First of all, the main harbor was so shallow that their ships could not dock there at all. Everyone and everything had to be lifted there by lighters, small craft that would ferry them to shore. Once there, they found a small city at the western end of remote Brittany, where even Frenchmen felt a little out of place. As they marched wearily down crooked streets, the bulk of the 36th Infantry Division were also greeted with gusto by the Bretons. Many lined the streets to cheer these Westerners, but they did not see any men of fighting age to greet them. What they saw were the elderly, women and children asking for pennies for food.

The French who greeted the 36th Division were about to enter their fifth year of relentless war. The war had taken healthy men to the front; their young orphans each wore a black apron. Children looked a little malnourished. Adults looked tired. The men working at the docks were German prisoners, who appeared well-fed. Most of the inhabitants wore wooden shoes, which surprised the men. “They say we get women’s fashions from France.” one soldier wrote his sister, “Well, the girls wear wooden shoes, so you will have to get you a pair.”

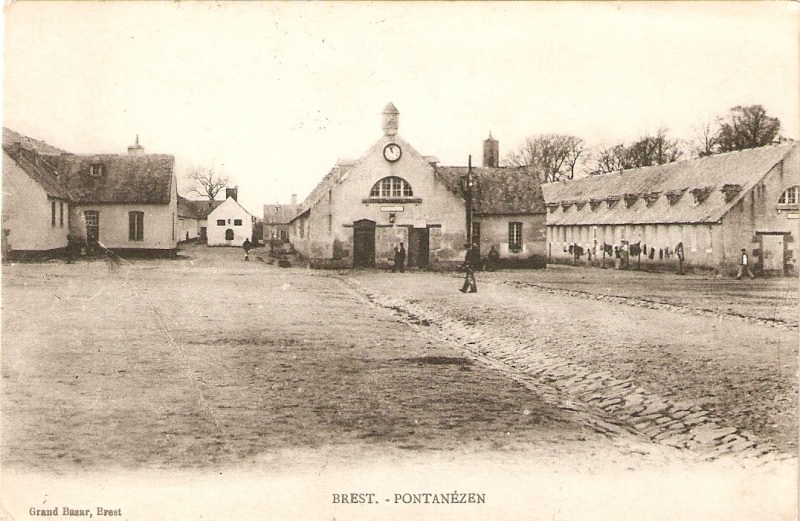

Pontanézen

A few miles uphill above Brest stood Pontanézen barracks. Pontanézen was a Napoleonic era complex of long stone buildings surrounded by a stone wall. It had served as an army base, then a prison and lastly as a rest camp for newly debarked Americans. The soldiers who were billeted there were not fond of it. Pontanézen offered cold stone floors, not enough bedding and only cold water to wash with. Locked in a stall, but still within view, was the guillotine from Pontanézen’s prison days.

Even less popular was what awaited most of the men a few miles beyond the old barracks: manure-strewn fields where most of the men had to sleep. There were no shelters except for the half-tent canvas square each man carried in his pack. After lashing that together with that of his tentmate, a soldier had only his woolen blanket and overcoat for warmth. Which would have been fine if they were still in Texas. But instead they were on the coastline of Brittany, where it rained almost every day.

What rest?

Food had to be prepared and eaten out in the field by the men. There were no permanent facilities there. And if you wanted to bathe, that was two miles back at the barracks. Men started coming down with colds and pneumonia. One man in the 142nd Infantry died at Pontanézen. Practically the only relief was the local wine and cognac. Stronger stuff like cognac was prohibited but still sometimes available to Americans in France.

Units in Pontanézen and the other rest camps stayed only until train transport to the French interior was organized. This was usually five to seven days. Then they would move on to the next phase, which was their final training. As for the men who were in rest camps around Brest, one remarked that “The only rest about them was that the soldiers who were so unfortunate as to pass through them would remember their awful experience there for the REST of their lives.”