Company A, Texas Engineers was a National Guard unit formed in the spring of 1916 in Port Arthur. In addition, Company B formed in Dallas later that spring. Because of the Border Crisis, the two companies were Federalized for service along the U.S. – Mexico border in the summer of 1916. The Engineers served, along with the rest of the Texas National Guard, until March 21, 1917. However, sixteen days later the United States was at war with Germany and these citizen-soldiers were again activated for duty. Company B traveled in June to San Antonio to build Camp Travis, future home of the 90th “Texas-Oklahoma” Division. Company A reported to Camp Bowie in August 1917.

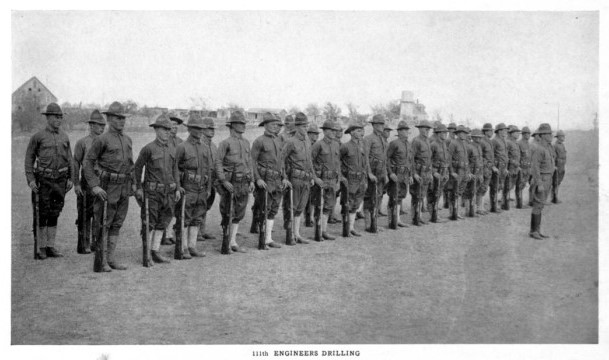

The Texas Engineers were enlarged with the addition of Company C from Sweetwater in West Texas. The companies joined together for the first time in August at Camp Bowie as the First Battalion, Texas Engineers. Joining the Texans was the First Battalion, Oklahoma Engineers, who were recruited in 1917. Together they formed the 111th Engineer Regiment, the Engineers of the 36th Infantry Division. In addition, the two battalions gained a Headquarters detachment, a Medical detachment and the 111th Engineer Train. They helped the U.S. Army Cantonment Division construct the camp and took over responsibility for completing it when the Cantonment Division left Camp Bowie in November, 1917. Their home stations were as follows:

1st Battalion, 111th Engineers

- Company A: Port Arthur, Texas;

- Company B: Dallas, Texas;

- Company C: Sweetwater, Texas

2nd Battalion, 111th Engineers

- Company D: Tulsa, Oklahoma;

- Company E: Ardmore, Oklahoma;

- Company F: Oklahoma City

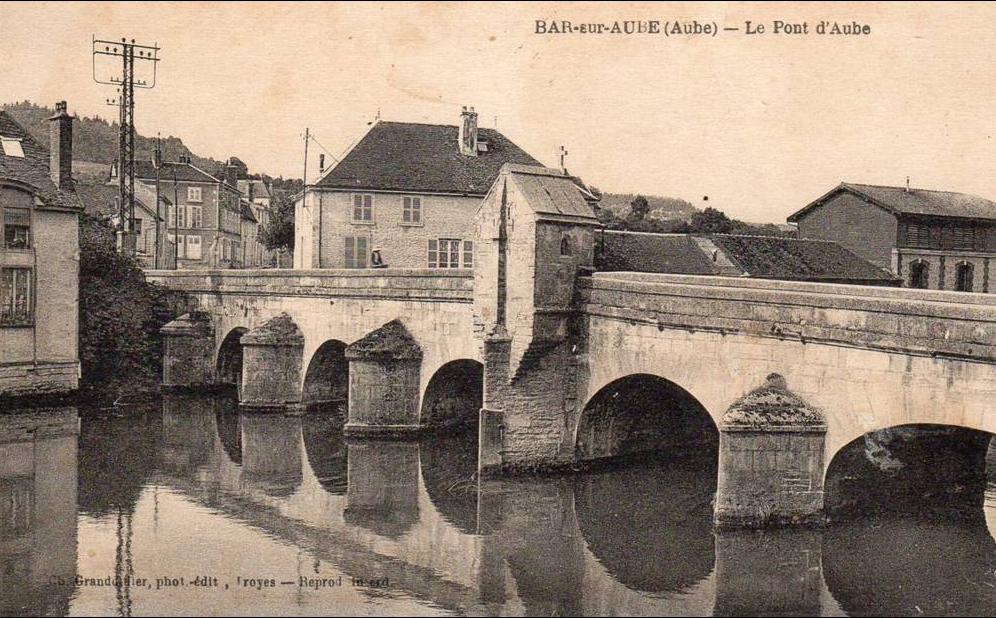

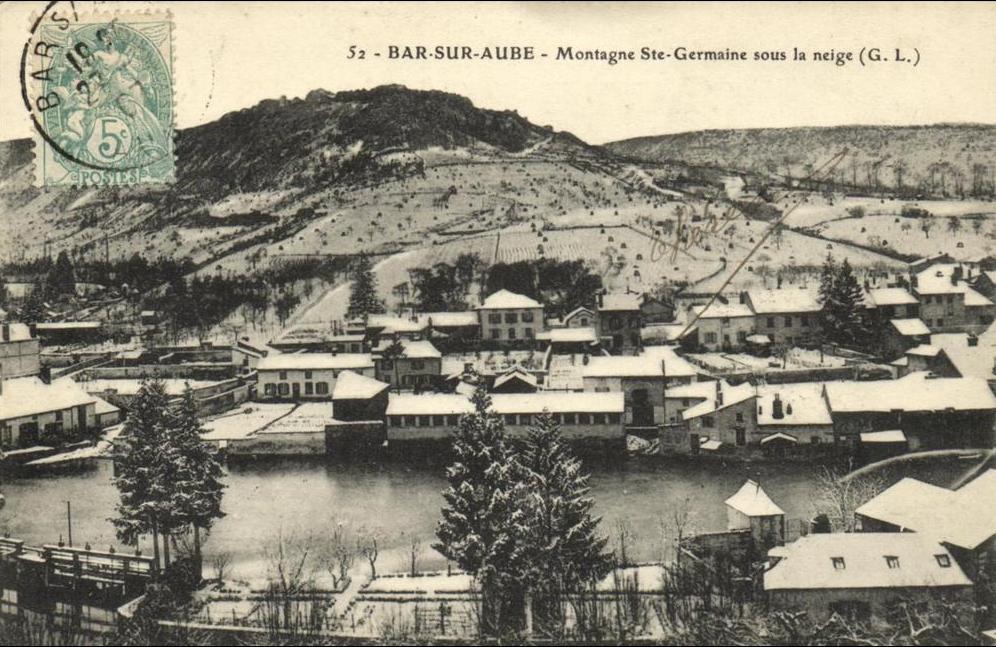

Training in France

On August 5th, 1918 the 111th Engineer Regiment arrived in Bar-sur-Aube, France with the 36th Infantry Division. The 36th was stationed there for final training. Headquarters for the 111th was in Spoy, a small village eight miles from Bar-sur-Aube. As the division engineers, the 111th was busy improving local roads, building rifle ranges and a grenade training area. They also dug model trenches for training and mapped the area as practice for the front. A U.S. Engineer Regiment in France normally had 1,750 members. However, the 111th had about 1,500 officers and men at this time.

Moved to the Front

On September 9th, 1918 the 111th Engineer Regiment was ordered to leave the 36th Infantry Division and report to I Corps, First U.S. Army at Frouard, one hundred miles away. The Texas – Oklahoma Engineers were going to war. The Engineers left Bar-sur-Aube on September 10th and 11th for the 10-hour train trip. Once the regiment arrived at Frouard, they unloaded their equipment and rested. On the morning of September 11, the regiment marched toward the front line past Griscourt, a nine-to-twelve mile journey. Consequently, the march took the regiment nine hours.

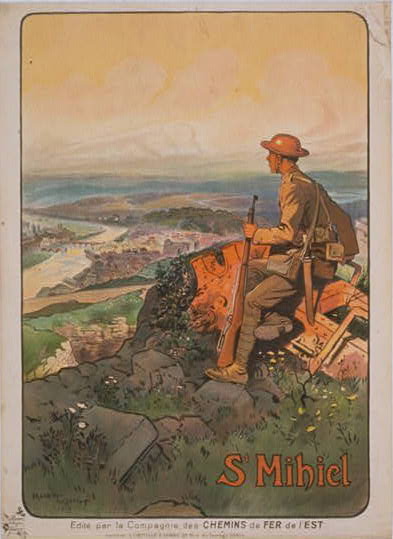

The first American-led attack of army-size in the war, the St. Mihiel offensive reduced a German bulge in the front line. The German Army had seized the area early in the war, in September 1914, and had eliminated French Army resistance inside the bulge by May 1915. The bulge stuck out over a dozen miles into France from the rest of the front, ending at the town of Saint-Mihiel. Busting the bulge would move the Germans back to the 1914 line. As a result, it would enable the Americans and French to send troops and equipment more easily by rail to their next objective, the Argonne Forest region.

Saint-Mihiel operation

The 111th Engineer Regiment made camp for the night in a forest just north of Griscourt at 6 p.m. At ten o’clock, the sky lit up and trees shook as American and French artillery opened up along the front. Seven American infantry divisions went across the front line near the 111th early on the morning of September 12. As a result, the regiment was on the road again by 8 a.m. By three o’clock the next morning, the 111th reached Regniéville-en-Haye, a village so badly ruined by war that it does not exist today. At Regniéville the regiment built a road through the ruined village for army trucks and artillery to aid combat troops just ahead.

It was at Regniéville that the 111th took its first fire from the Germans. Artillery shells were a real danger for Engineer troops working just behind the front line. The first shells on September 13 killed some horses. German planes would fly over at night and drop bombs on the engineers. On the 14th, the regiment continued to build roads over captured trenches and shell craters. After that, they made their way another six miles to Thiaucourt, where they met newly-liberated French civilians.

After repairing the roads around Thiaucourt, the 111th Engineers started their march from the front at 3 p.m. on September 15. Away from the front, but not from danger. On the evening of the 16th, they were shelled near the village of Blénod and three men were wounded. The next night, gas shells hit near their camp at Dieulouard. After six days in the St. Mihiel salient, Texas-Oklahoma engineers had tested their mettle.

Meuse-Argonne

With the St. Mihiel pocket reduced, it was now time to prepare for what became the largest offensive of the war. Over one million American soldiers and marines would participate in the Meuse-Argonne Offensive. The French-American plan was to push through the Argonne Forest to the Meuse river and seize the fortress city of Sedan. If the Germans lost Sedan and Metz to the southeast, they would lose rail transport networks and their famous Hindenburg line of defenses. As a result, they would have little option but to retire back to Germany.

On the march

The front lines in the Argonne Forest were sixty-five miles away. To get there, the 111th Engineers would have to walk once again. They left Dieulouard on September 17th at 7 p.m. and marched all night. Along the way they passed a line of captured German artillery two miles long. The next morning they camped just past Sanzey, sixteen miles away. The regiment would march at night on their way to the Argonne Forest, which kept them safe from German artillery. By 5 a.m. on September 19 they had possibly reached Sampigny, 20 miles from Sanzey.

Two days later the Texas-Oklahoma Engineers were in Èvres, 26 miles away. By this point the roads are clogged with soldiers on their way to the front, and the going is slow. In addition, some of the men were coming down with influenza and had to be hospitalized. Americans in France all remembered the near constant rain. It had rained for much of the time the 111th was on the move.

By September 23rd the regiment was in Les Islettes, 15 miles from Èvres. In seven nights of marching the 111th had gone about 77 miles though northeast France.

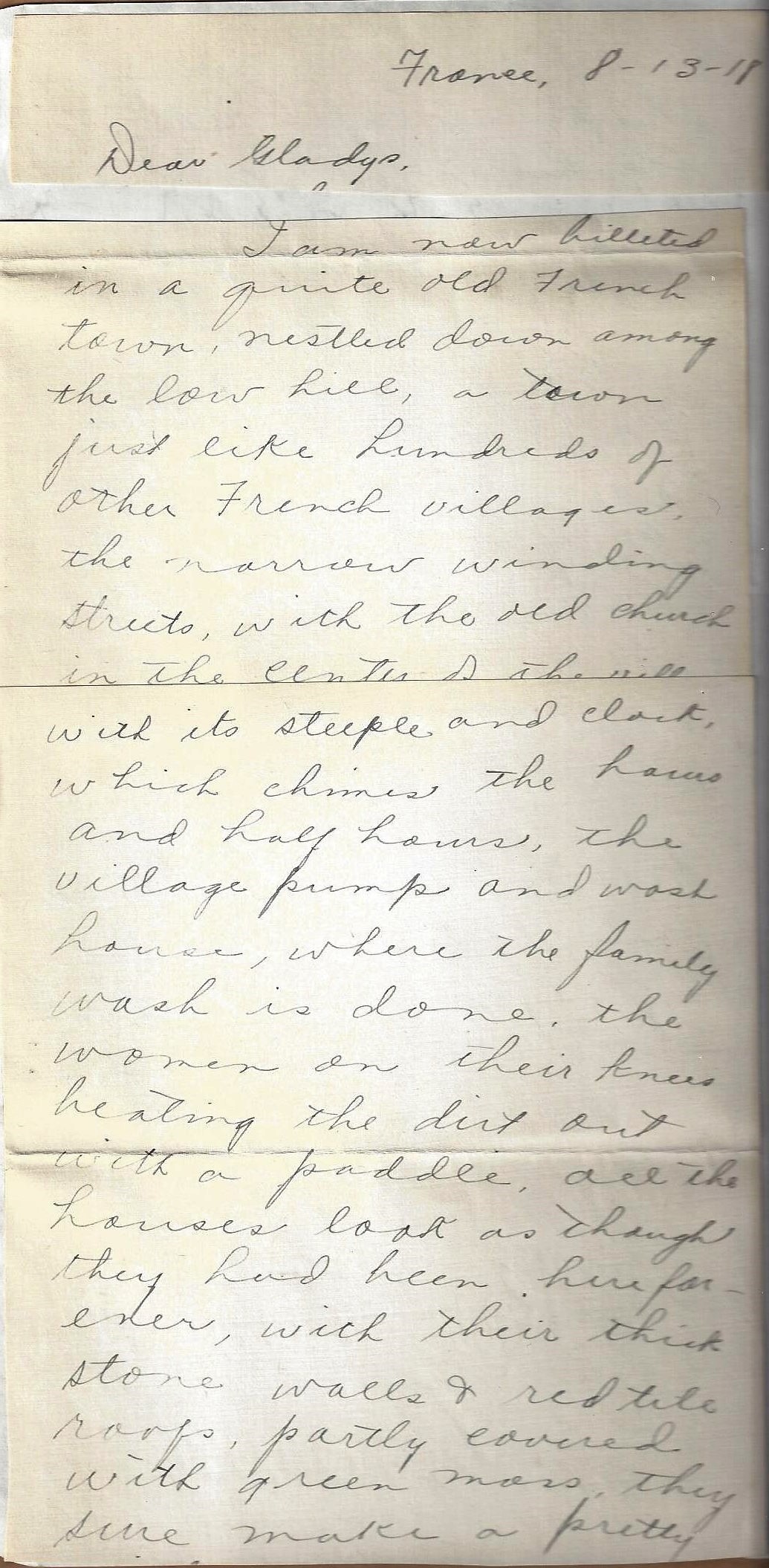

(Read about the experience of Corporal Walter G. Sanders, Company B, 111th Engineers in France in Judy Duke’s post to WWI Texas History here.)