On October 4th, 1918, men of the 142nd Infantry were preparing to leave Champigneul, a village near the Marne River in northeast France. The 142nd was part of the 36th Infantry Division, headquartered in Pocancy, the next village to the south. The 36th Infantry had been living in villages near the south bank of the Marne River for six days, waiting to go to the front. Just eight days before, on September 26th, allied forces attacked the entire German line in France and Belgium. It was, and remains, the largest land battle in U.S. military history.

Only the 36th Infantry Division was not with the American army. U.S. General John J. Pershing had loaned the 36th to the French Army for the battle, where it expected to stay in reserve behind the front line. The 36th had just cut short their training to join the Groupe d’armées de Centre, who were fighting alongside the U.S. First Army. Most noteworthy, the 36th Infantry had no combat experience, and had never been to the front. When it entered combat, according to the plan, the 36th Infantry would push through the French countryside after others had broken through German fortifications.

For France

During their short stay south of the Marne the men of the 36th experienced firsthand glimpses of war. Hundreds of buildings stood in ruins from artillery and aircraft attacks. The appearance of German planes brought the Southwesterners out of their billets to watch. Some of the towns were attacked, while Texans and Oklahomans took shots at German aircraft with their rifles.

Meanwhile, the 36th did their best to get equipped for combat. The French gave them the correct number of mortars, flare pistols and grenades. The men carried out drills as best they could during that week along the Marne, staying out of sight of German aircraft. At night they would look to the north and east to watch and hear artillery duels from the battle just beyond the horizon.

To the front

In nearby Champagne, German and French armies faced one another from more or less the same trenches since September 1914. The French had suffered great losses twice in 1915 trying to push the Germans out. Since 1914, the Germans had built concrete bunkers in multiple lines of defense. The last French offensive, in September 1915, cost them 145,000 casualties. The defending Germans regained all lost ground during the battle at half the cost in dead and wounded. Over three years the French and Germans expanded their fortifications. Germany’s Hindenburg line was a system of machine-gun bunkers, observation posts and underground shelters that stretched across the region.

Three years later, in September 1918, the French attacked in Champagne. French soldiers were able to capture parts of the Hindenburg Line. Still, after two attacks, they were unable to break through a German stronghold in the Champagne countryside called Blanc Mont. Visiting there today, you can see why: a long hill bristling with bunkers with a clear view for miles around. The French sent in a fresh division, the U.S. Second Infantry, to take Blanc Mont.

Send the Second

The reputation of the Second Division is the stuff of legend (“Second to None”, if you ask them). One of the first U.S. divisions to become active in France in 1917, the division included one Army brigade and one Marine brigade. In June 1918 the Second Infantry blunted the German spring offensive at Belleau Wood, saving the city of Paris in the process. It was a desperate, costly fight that neither side could afford to lose. German attackers were amazed at the fighting spirit of the inexperienced Yanks, who turned them back in spite of terrible casualties. On June 26th, 1918, silence in Belleau Wood was followed by a dispatch from Major Maurice Shearer, 3rd Battalion, 5th Marine Regiment. It simply said:

“Woods now U.S. Marine Corps entirely.”

Blanc Mont

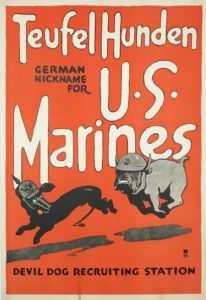

On October 3rd, 1918, the U.S. Second Division attacked the system of fortifications at Blanc Mont and captured it within two hours. In doing so, they had advanced a mile and a half beyond the nearby French lines and so were exposed on their left and right. Facing the enemy on three sides, the Second Infantry held their ground despite German counterattacks. The Americans held a narrow wedge of territory, 500 yards wide, inside the German defenses. Try as they might to push forward, further German strong points made this impossible. Artillery shells were landing on the American position from close range. U.S. soldiers and marines dig in and kept watch for an assault.

The next day, October 4th, the Germans counterattacked on the left flank of American positions, which were held by Marines. There was also heavy fighting on the right side, which was held by the Army. On that day and the next, October 5th, the Americans tried to advance but could not. The fighting was intense and losses were heavy. The American-French force had broken through German defensive lines and wanted to expand beyond them. The Germans were determined to resist because retreating would endanger other German troops fighting the main American army in the Meuse-Argonne sector.

Marine veterans of Belleau Wood said the Battle of Blanc Mont Ridge was the tougher fight.

Call to the 36th

French and American commanders agreed reinforcements were needed immediately. The 36th Division was called to the front. On October 4th, half the division traveled by truck about 31 miles from Champigneul to the ruined town of Suippes. The journey took all night and the 142nd Infantry marched the last two miles to their first stop, Somme-Suippe. The 142nd waited at Somme-Suippe on October 5th for the other half of the 71st Infantry Brigade, the 141st Infantry Regiment, to arrive. On October 6th the whole brigade marched north to the town of Somme-Py, about 11 miles. On their way the 71st Brigade made its way through the Hindenburg Line, taken by the French in the first days of the battle. Here, Texans and Oklahomans saw French and German dead on the battlefield. When they got to Somme-Py, the U.S. Second Division had ammunition and supplies there waiting for them.

The rest of the way, about four miles, was under German observation and would have to be crossed at night. The commanders of the 141st and 142nd Infantry reported to Marine Major General John A. Lejeune, commanding the U.S. Second Division, for orders. The order was for the 71st Brigade to make its way to the front and relieve the entire 2nd Infantry Division.

At the front

The men of the 142nd Regiment spent late afternoon and evening of October 6th near Somme-Py taking as many supplies as they could carry. Company commanders tried to get their hands on maps of enemy positions and water for the men. Marines were expected to guide them to the front, but they had taken shelter while the Germans were shelling the town. However, soldiers of the 142nd did not meet their Marine guides until after nightfall. Since the Marines had arrived by truck in daylight, they did not know how to get back to the front by foot. Finding their way forward in the dark was trial by error, and the men quickly became lost. As a result, the 142nd Regiment did not get on the right track until late at night.

The untested soldiers were now on their way to war. Second Division Marines on their way to the rear passed them as they advanced and remarked of the National Guardsmen “singing and joking as they went. High words of courage were on their lips and nervous laughter.” One Marine told another, “Hell, them birds don’t know no better…Yeah, we went up singin’ too, once–good Lord, how long ago!…they won’t sing when they come out, or any time after.”

The soldiers had witnessed German artillery hits that afternoon near Somme-Py. Now that they were moving nearer to the front, exploding shells were closer and closer. The Germans had targeted crossroads especially, and soldiers were held up at them waiting for a pause in the shelling. Three men were killed by German artillery, the first combat losses in the 142nd.

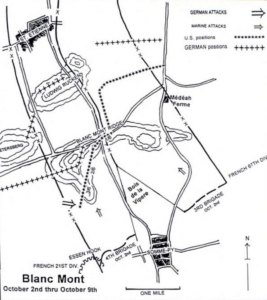

Dug In

It was daylight, October 7, when the 142nd reached the front line. The battlefield was not like anything they had trained for: a series of foxholes and shell craters with the occasional abandoned German dugout was their shelter. The Germans were about 100 yards away, and had seen them arrive. Machine guns opened up on the Americans and soon artillery shells exploded nearby. Men dug their own holes or leaped into foxholes just vacated by the Marines. Germans could be seen across no-man’s land, moving from dugout to dugout. That afternoon, artillery hits were more severe with American dead and wounded.

Commanders in the 71st Brigade spent a frantic day completing the relief of the Second Division and locating supplies and ammunition. Later on, a French tank battalion showed up, which encouraged the men. Maps were in short supply and not useful when commanders got them. Lastly, there was only one day’s supply of food and water; what each man had carried there.

That night, commanders made their way back to Somme-Py for final orders. At that moment they learned that they would attack the German line. Major General Lejeune had asked his French commanders that the 36th spend a few days getting used to combat operations before going on the attack. His superior, French XXI Corps commander General Stanislas Naulin, disagreed and set the attack to resume at dawn on October 8th with the 71st Brigade in the lead.

Learn more about the battle on the 8th of October:

Conspicuous Gallantry and Intrepidity

Resources

Texas Military Forces Museum: The 71st Brigade at St. Etienne