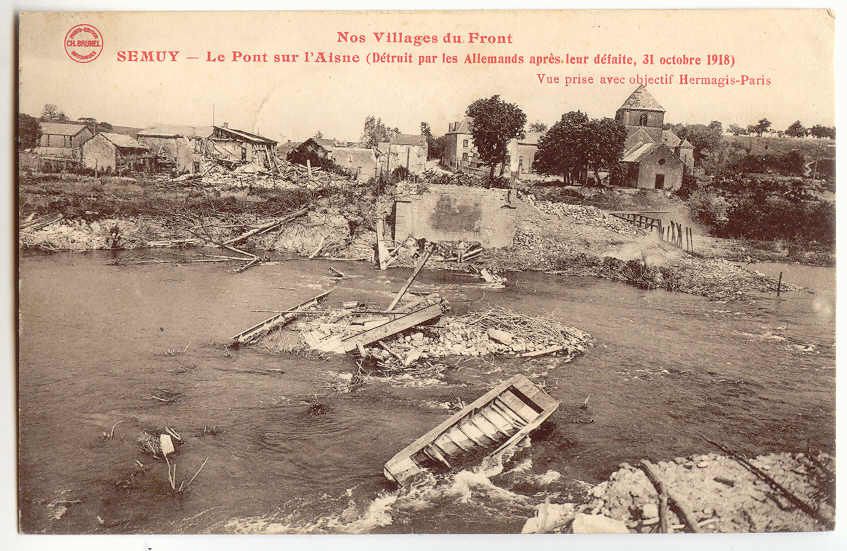

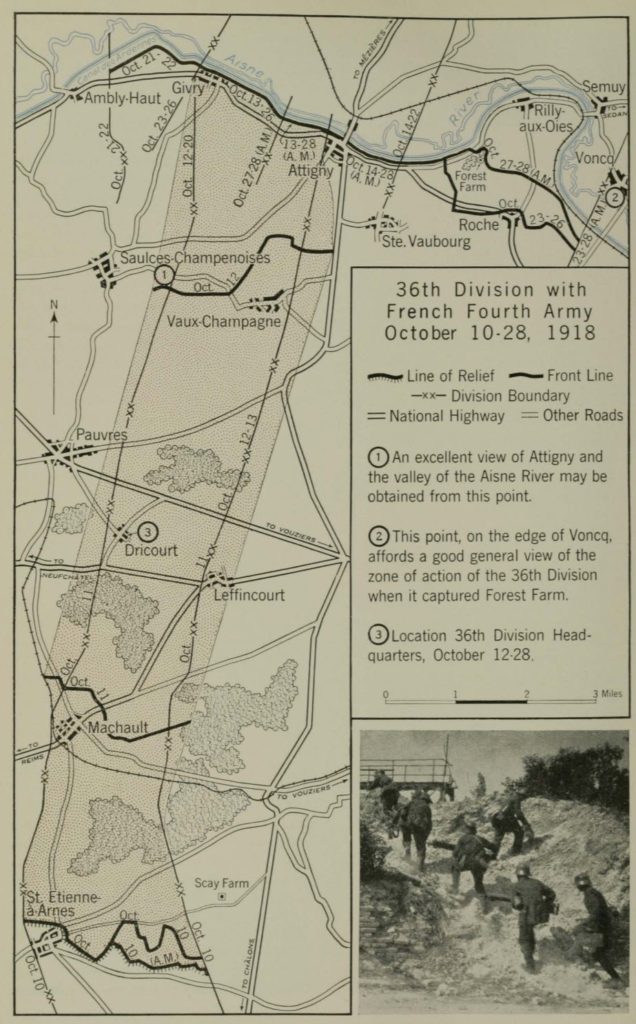

Mid-October 1918 had American and German forces facing each other in an uneasy standoff. The Germans were dug in on the north side of the Aisne river in the Champagne region of France. The Americans were on the south bank, with the French Fourth Army. The French wanted an attack across the river around the town of Attigny. But the Germans had blown up all the bridges. Rows of barbed wire and machine gun pits lined the German side. Getting across the Aisne required a strong force, and a plan.

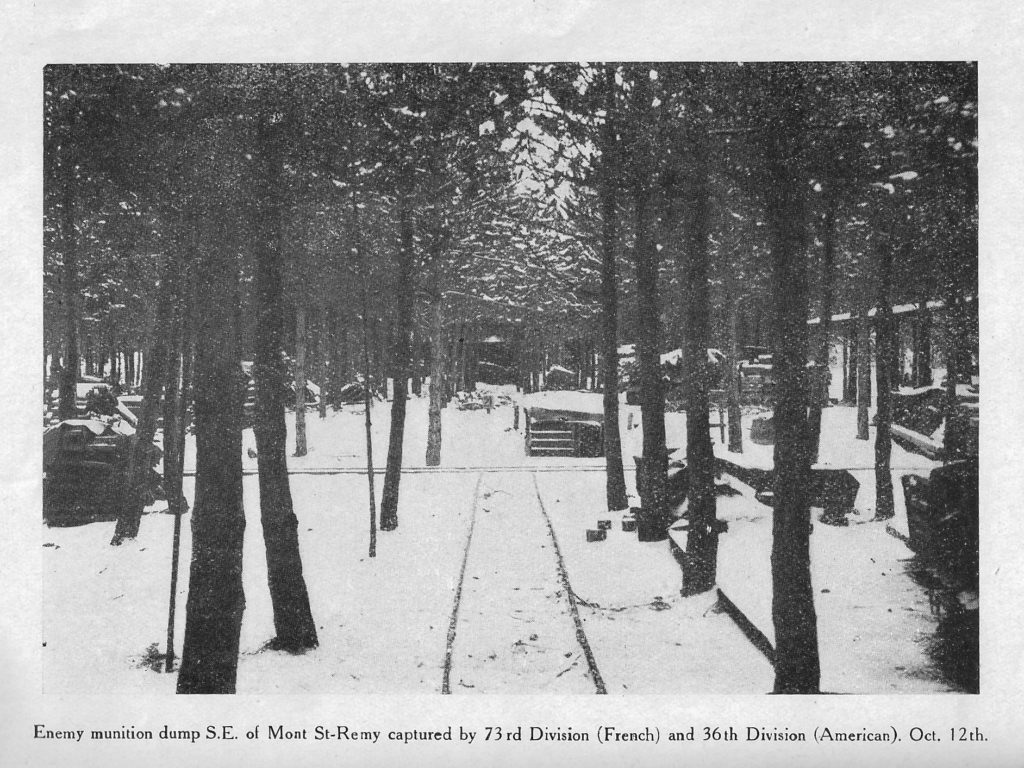

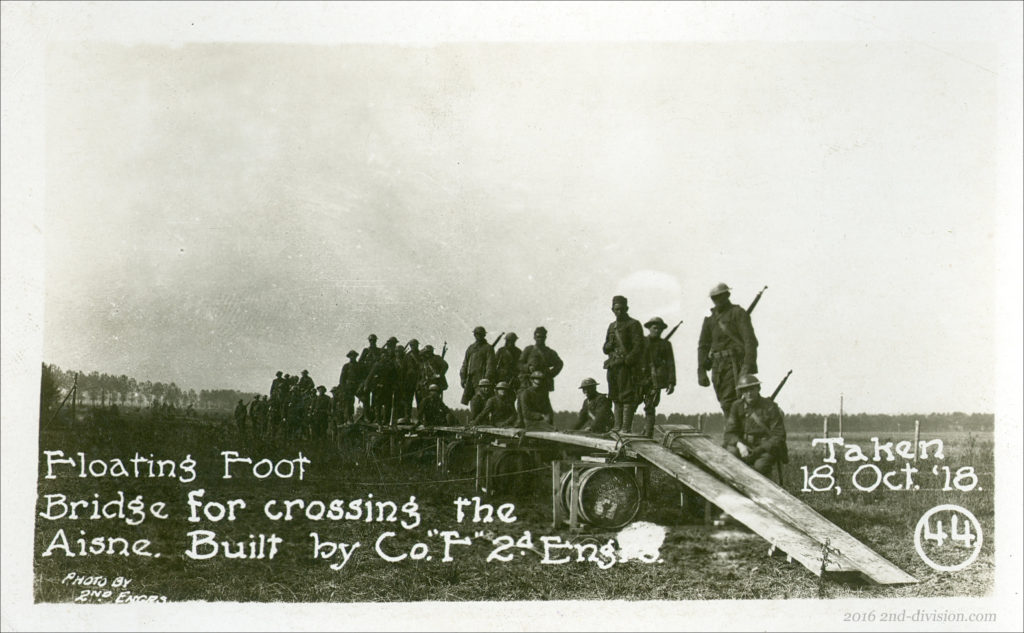

Commanders, including the American one, were working on it. With the American 36th Division was the 2nd U.S. Engineer Regiment. The Engineers had their work cut out for them: First of all, they had to repair up to forty miles of roads to get men and supplies to the front line. Second, the Germans had left a narrow-gauge rail network in ruins when they retreated. Repairing the railroad would help bring ammunition and supplies to the men at the front. Also, the Engineers had to work out how to get soldiers across the Ardennes canal and the river in a surprise attack.

Engineers get to work

The Germans had left behind lots of finished lumber, so the Engineers got to work. The goal was to build portable but sturdy footbridges to get the men over. Engineers built a number of bridges and tested them. The designs were ingenious but using them in combat was going to be no picnic. (More about the 2nd Engineers with the 36th can be found here.) The Aisne river valley was a war zone, with hundreds to over a thousand artillery explosions every day. Machine gun fire crossed a deadly no-man’s land. Snipers active on both sides made it risky to leave shelter during daylight.

Refugees

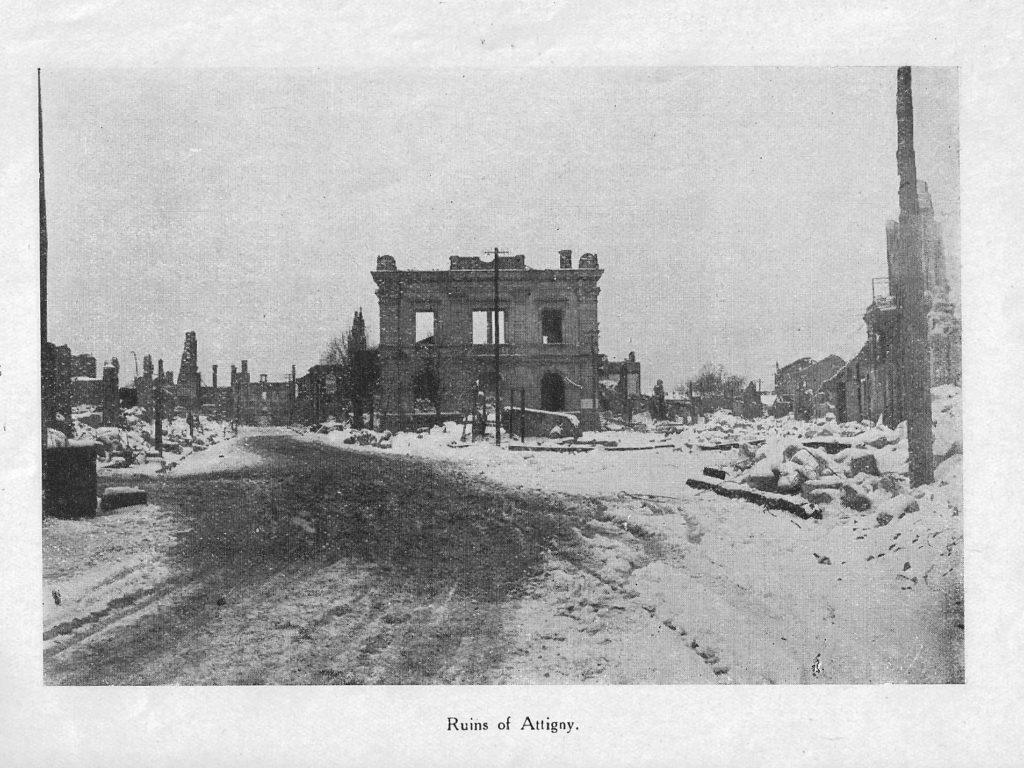

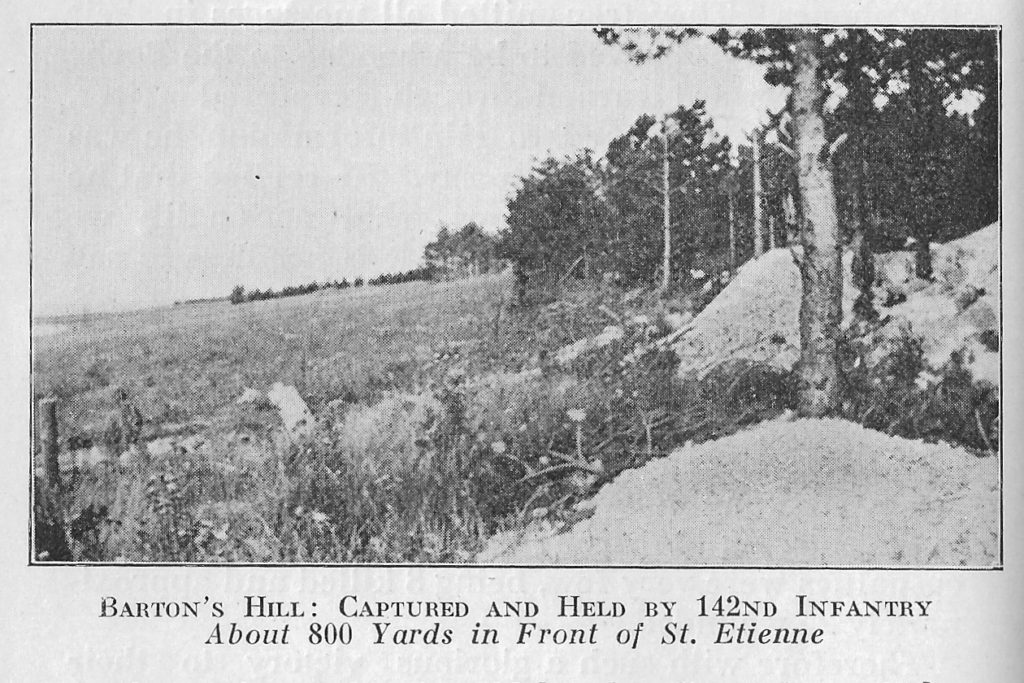

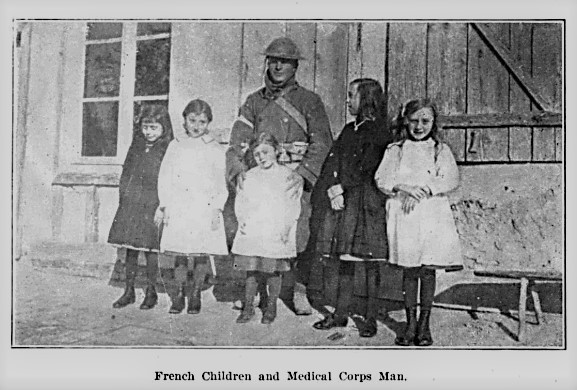

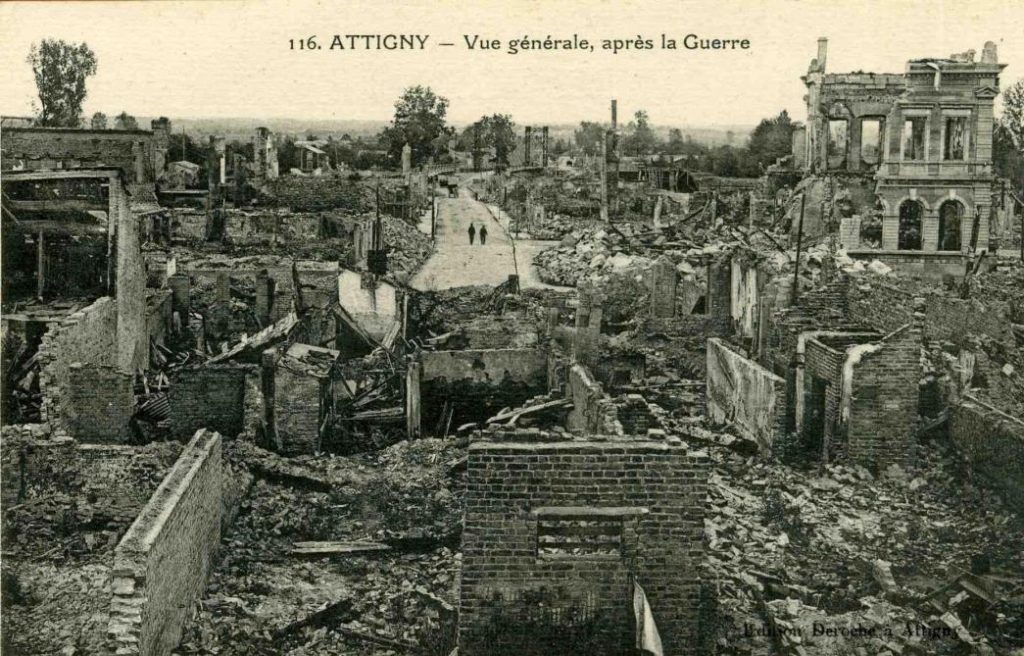

When the Americans fought for ruined towns like Saint-Étienne, they were abandoned. This was not the case when the Allies advanced farther into German-held territory. The towns of Attigny, Givry and others had a civilian population, now liberated after four years. Now that Attigny and Givry were wrecked by fire and shelling, civilian refugees had gathered in nearby Sainte Vaubourg. About 1,200 French civilians, mainly elderly and children with their mothers were trapped by artillery fire. They hung white sheets from every building in Sainte Vaubourg, which seemed to work.

Allied forces worked together to evacuate them. A column of trucks arrived to take the refugees south toward safety. However, as they were leaving German artillery struck the column and some of the civilians were injured. A first-aid station was also hit, despite its prominent red cross marking.

Reconnaissance

If the Allies were going to attack over the river, they would need to know what was on the other side. Both sides hid themselves during daylight but commanders wanted to know German strength just over the riverbank. Once again they turned to First Lieutenant Donald McLennan, scout officer in the 142nd Infantry. Just days earlier, Lt. McLennan had led a patrol over the river, capturing two German prisoners. Returning to 1st Battalion headquarters after another night patrol on the front line, McLennan received orders for a risky daytime operation. McLennan continues,

“I explained that I had just got in from reconnaissance and told them of German locations, and that it was my belief that we could not cross. It did not change the order. I called for volunteers and Ted Watrous and ‘Red’ Smith, who had served me so well on a former occasion, stepped out, also Corporal Allie Gammill and Buster Stinson. I told them what was wanted also informed them as to what I knew of the conditions. I instructed them to go to the old mill and take observations but under no circumstance try to cross the canal, but wait for me.”

While the patrol made their way to the observation post by the canal, McLennan received confirmation of the order. He gathered a support team of ten riflemen to cover his incursion into enemy territory. Once the ten were in place on the American side of the Aisne River, McLennan started for the canal with Watrous, Gammill, Stinson and Smith.

Crossover

“When we arrived at the canal I told the men I would go ahead, and when I fell to go back and report that we had contact. We worked cautiously trying to get a small raft, and finally got some men across. We were just starting to advance a little when the Germans opened up. I stooped over and the man behind me was shot in the shoulder, another across the forehead.”

McLennan’s patrol had been observed as it crossed over. Now Germans were coming across no-man’s land between the river and the canal to block their escape. McLennan ordered the surviving members of his patrol to withdraw. Then he stepped out in full view of the enemy and emptied his M1911 Colt at them. He walked backwards, still firing at the advancing Germans. “We’re going back,” McLennan called out, “but I’ll face you!”

First Lieutenant McLennan and Private Lester “Red” Smith miraculously got across under covering fire from his team on the south side of the canal. But McLennan was right about making patrols in daylight. He lamented,

“Ted Watrous and Corporal Gammill were killed and Stinson captured before we could get away. I returned to Headquarters and told them we were in contact.”

A new motto

For his actions at Attigny on October 21, 1918, First Lieutenant Donald J. McLennan was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for heroism in action. When the unit crest of the 142nd Infantry Regiment was created after the war, the Steeple from Saint-Étienne, the Aisne River, and the words “I’ll Face You” symbolized the service and sacrifice of Southwesterners on the fields of France.

Private First Class Ted Watrous and Corporal Samuel A. Gammill were never found. They are remembered on the Tablets of the Missing at the Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery, located on ground liberated by American forces in 1918. More about America’s Missing in Action and the efforts to locate and remember them can be found here.