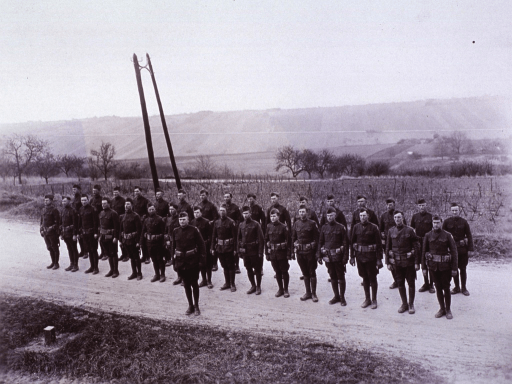

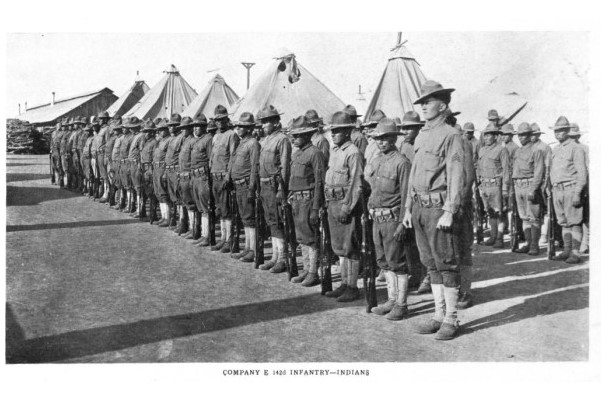

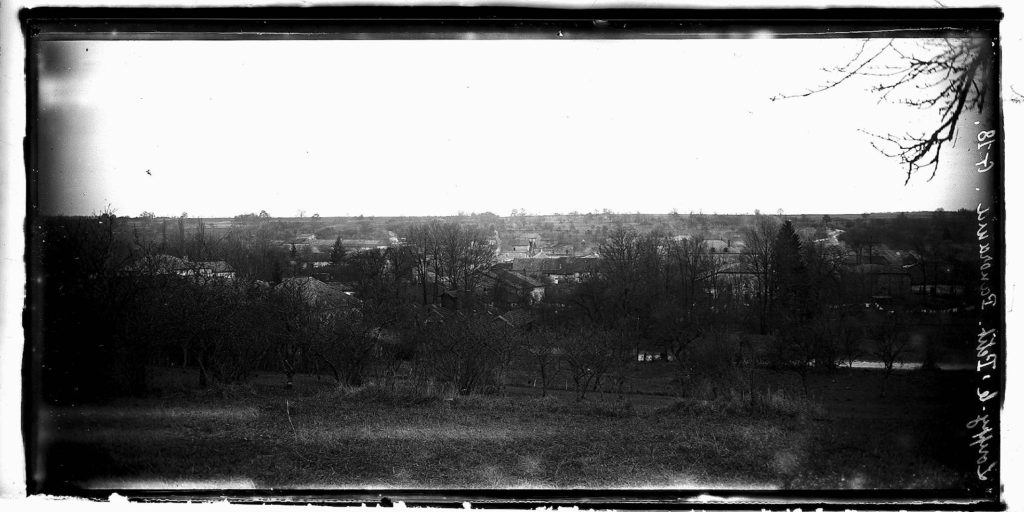

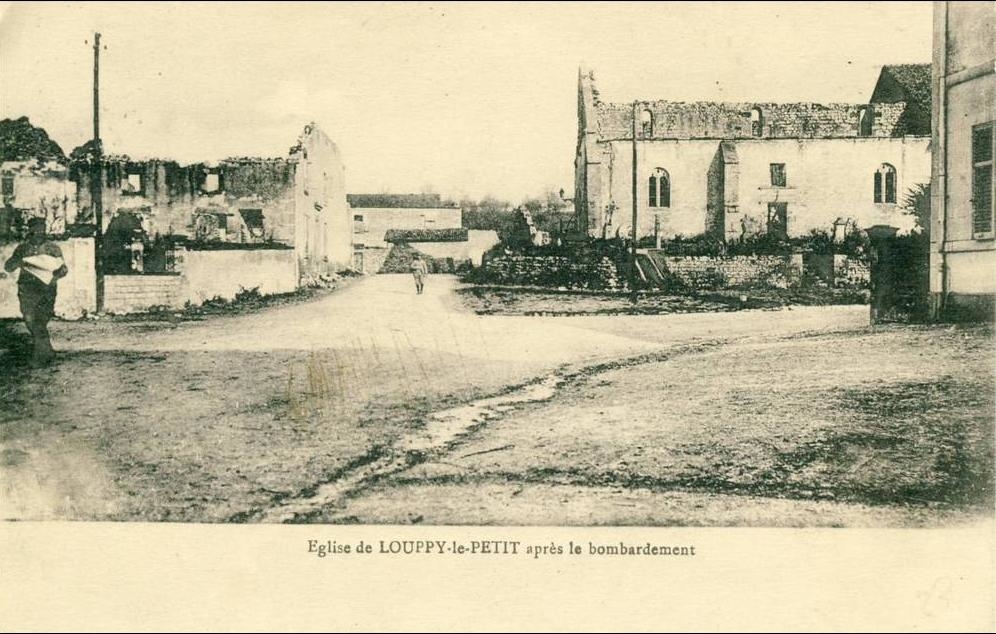

On November 11, 1918, the men of the 142nd Infantry Regiment were at drill practice in the tiny village of Louppy-le-Petit. The whole division, 36th Infantry, was preparing to reenter the battlefield. Just miles away raged what remains the largest land battle in American history.

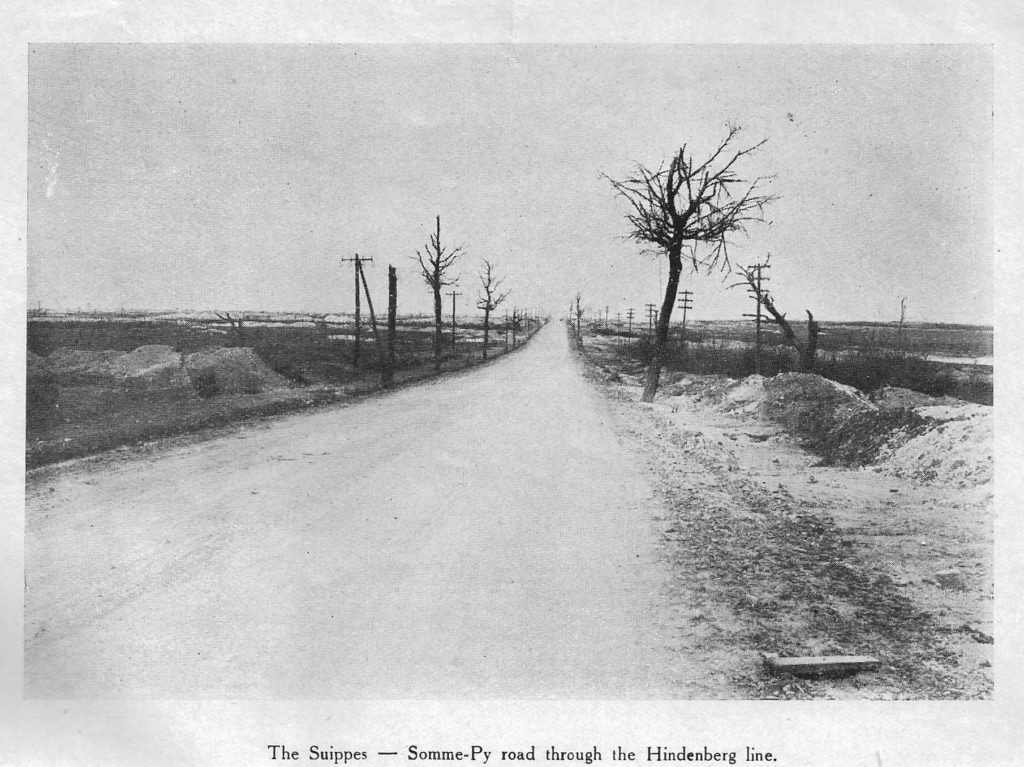

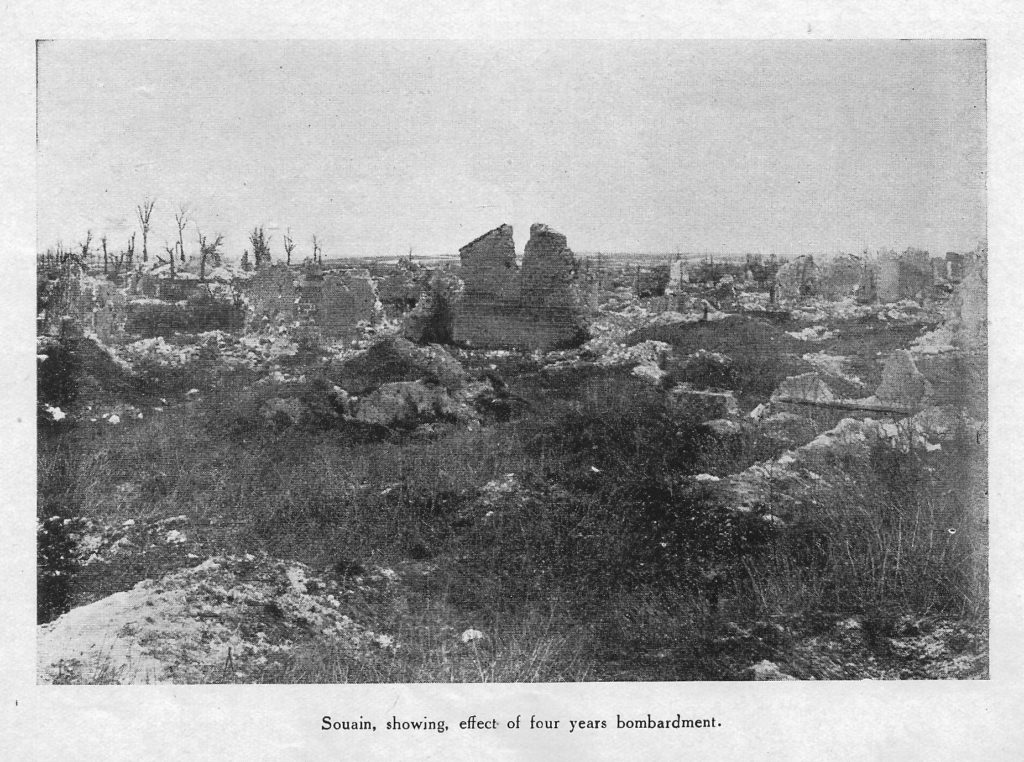

The Meuse-Argonne Offensive had started just before midnight on September 25th, over six weeks before. A massive cannon bombardment opened the attack and advancing American and French soldiers burst into German defenses. After surprising gains by Allied forces in the first two days of fighting, the German armies organized themselves. The American advance grinds to a halt. Consequently, casualties were high on both sides.

Since early October the American front had been reorganized twice, with depleted divisions taken out of the fight and new ones taking their place. For example, it took three weeks and 100,000 American casualties to reach the first day’s objective. Some American divisions had never been in combat before, others were seasoned veterans by now.

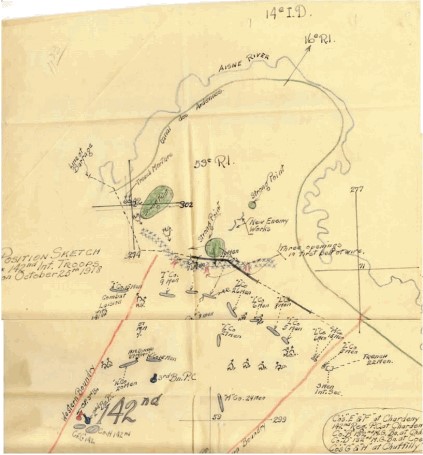

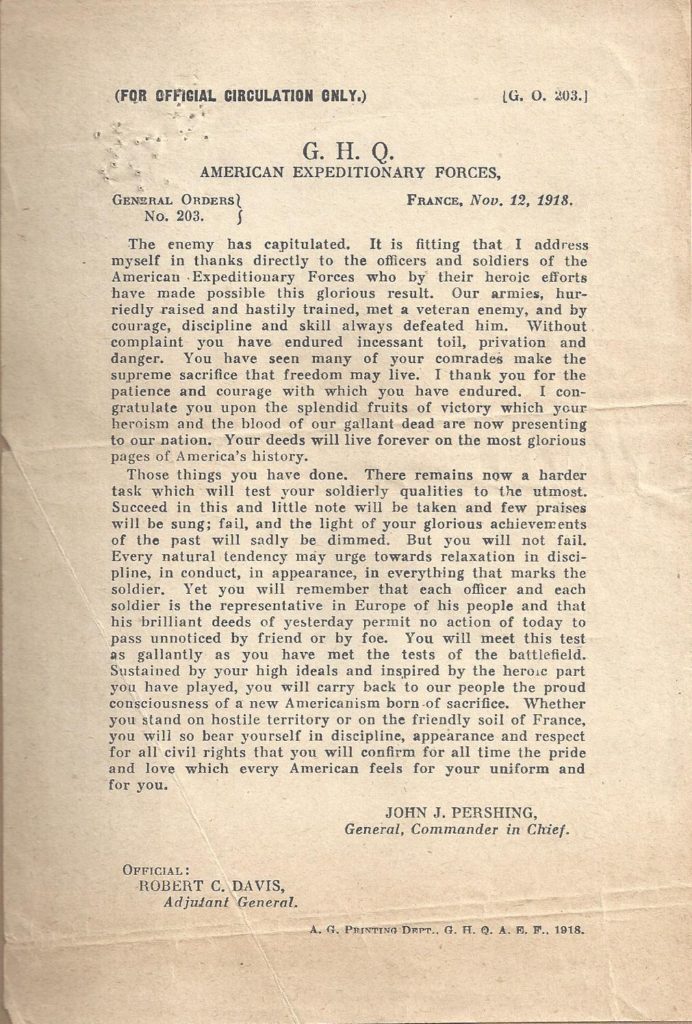

American commanding General John J. Pershing was now, in November, preparing a fourth phase of the Meuse-Argonne battle. He’d created a Second American Army and placed the 36th Infantry Division in it. In a renewed attack on November 1, American forces had smashed through the German line and forced a general retreat. Now American soldiers and marines are advancing miles per day where before it was just yards. Further, Pershing’s fourth phase was to begin on November 14. With it, he intended to break the back of the German Army and force it all the way home.

Germany offers a cease-fire

German military leaders, after flip-flopping for weeks, finally admitted to their government that the war was unwinnable in late October. Civilian leaders in the German government requested peace talks with the Allied powers and, on November 7th, sent a peace delegation to France. French terms, however, were uncompromising; but the situation was growing dire. An agreement was worked out on November 8th and governmental leaders on all sides considered their assent. In addition, Kaiser Wilhelm II abdicated his roles as Prussian king and Kaiser of the German Empire. A new German government indicated on November 10 it was ready to accept terms.

On November 11th, the German peace delegation was in France to sign a cease-fire, or Armistice. Once again, they went to the headquarters of the Supreme Allied Commander, French general Ferdinand Foch. The Germans signed at 5:12 a.m., Marshal Foch and his British counterpart signed at 5:20 a.m. There were no Americans (or Belgians, another important ally) at the meeting. (Read more about the signing of the Armistice here.)

Word reaches the 142nd

The Armistice called for the cessation of hostilities that day, at 11:00 a.m. Paris time. American general Pershing’s headquarters was notified at about 6 a.m. As a result, word reached the 142nd Infantry Regiment by radio later that morning. The 142nd was behind the lines training and had expected to be on their way to battle when the news arrived. As 11 a.m. approached, they could hear the artillery fire at the front getting louder. Soldiers of the 142nd wondered if, through some act of treachery, the Germans had decided to counterattack. However, the increase in artillery fire in the last hour of World War One was nothing more than artillerymen firing in order to have no shells to carry back.

Eleven o’clock a.m. on the eleventh day of the eleventh month passed, and the firing stopped. The fighting was finally over.

The celebration begins

Concerns of fighting again gave way to thrilling release for the men of the 142nd Infantry. As an eyewitness put it,

“That night the little, shell-torn village of Louppy-le-Petit, woke up. It had lain dormant for almost four long years. That night it was lighted by all the lights that could be obtained. The 142nd Infantry Band broke the stillness that had shrouded that sleepy little town, and inspiring strains of music vibrated through the hills. The inhabitants were hilarious and mingled with the Americans as they gave expression to their feelings.”

The celebration continues

“On the morning of November 12th, about 11 o’clock, the solemn tones of a funeral dirge came floating into Regimental Headquarters. No one knew what it could mean…”

“Soldiers will be soldiers and what one cannot think of the other will. They had planned to bury the Kaiser. There before the inhabitants and a street crowded with soldiers, came the Band leading a procession. Slowly and apparently mournfully they passed along.”

“Behind the Band, with a step measured and slow, marched tall, slim “Gloomy Gus” of Headquarters Company. He wore a long coat for a robe and in his hand carried an open book, thus representing the “Sky Pilot”. He was followed by four supposed pall bearers carrying a stretcher upon which was the supposed Kaiser. Following these was a long line of supposed mourners.”

“The seriousness of the occasion, and the splendid manner in which it had been carried out, was appealing. The procession proceeded leisurely to the bridge, and, after due ceremony, the remains were raised tenderly to the bannister and at the proper time were gracefully dropped into the creek.”

“The Band lit up a lively tune and amid cheers returned to quarters feeling they had expressed themselves.”