By October 22nd, 1918, the 36th U.S. Infantry Division was anticipating its relief. It had spent two weeks on the front and had advanced over thirteen miles. The 36th had suffered over two thousand casualties. A planned attack over the Aisne River, where the 36th Division was located, was postponed.

Meanwhile, over twenty miles away, a larger battle roiled the French countryside. The Argonne Forest area was witness to what is still the largest land battle in U.S. military history. The battle was entering its fifth week and was chewing up American and French divisions almost as fast as they could enter the fray.

The 36th Division was needed in the Meuse-Argonne. To get there, they would have to finish their fight in the Champagne area.

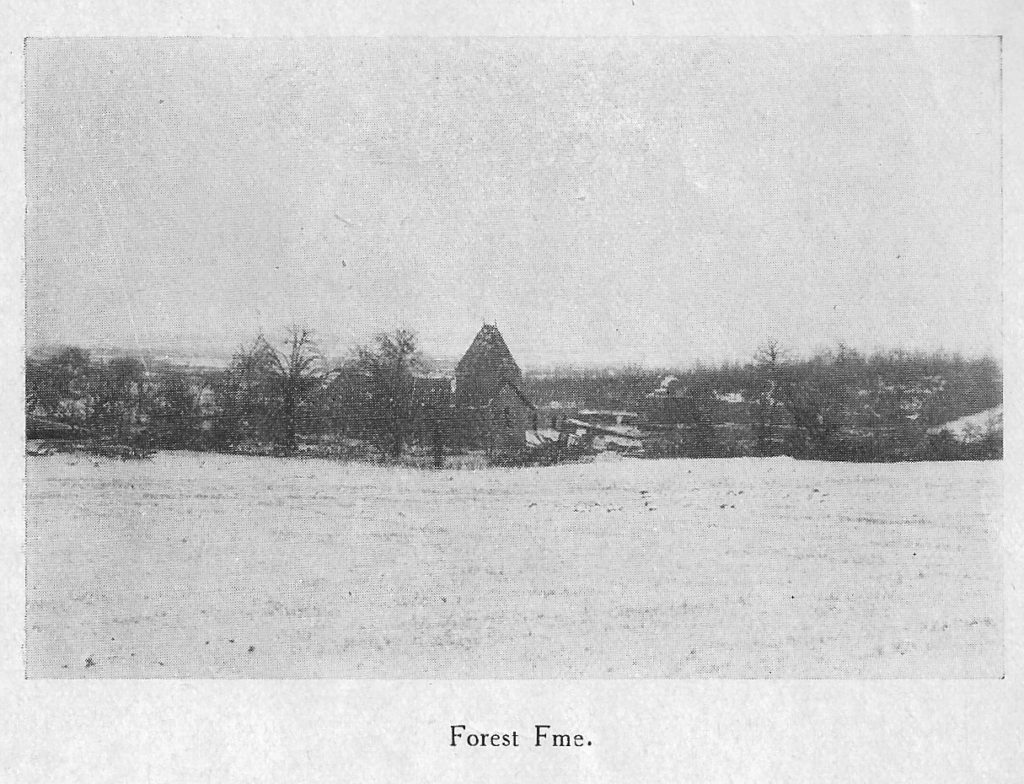

Forest Farm

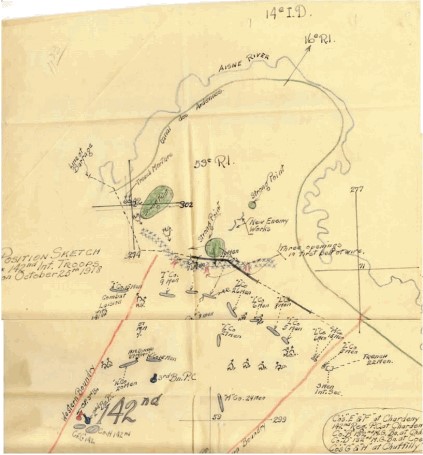

The 71st Brigade of the 36th Infantry Division (141st and 142nd Infantry Regiments, plus the 132nd Machine Gun Battalion) moved into a new position on the night of October 18. This position was directly in front of a German outpost on the south side of the Aisne River. It was the only German presence on the south side of the river for miles. Two previous attempts by the French 73rd Infantry Division to seize the position had only minimal success. German observers in the outpost could direct artillery with deadly effect. For example on October 22nd, a shell burst near the 142nd Infantry Headquarters, killing three men.

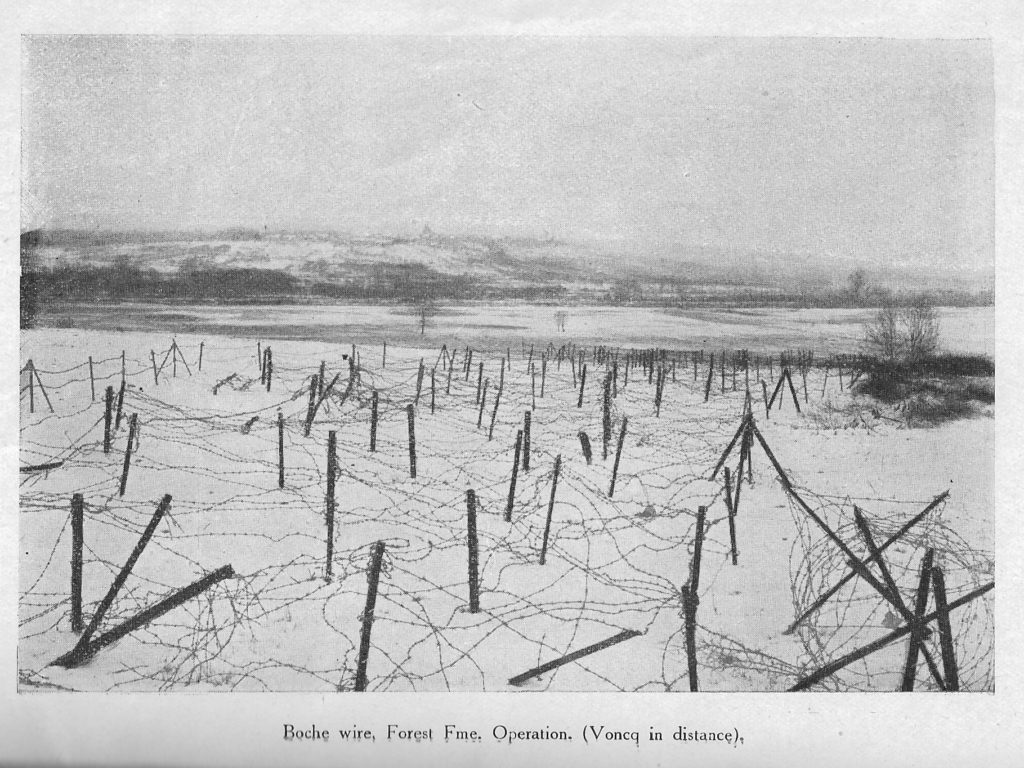

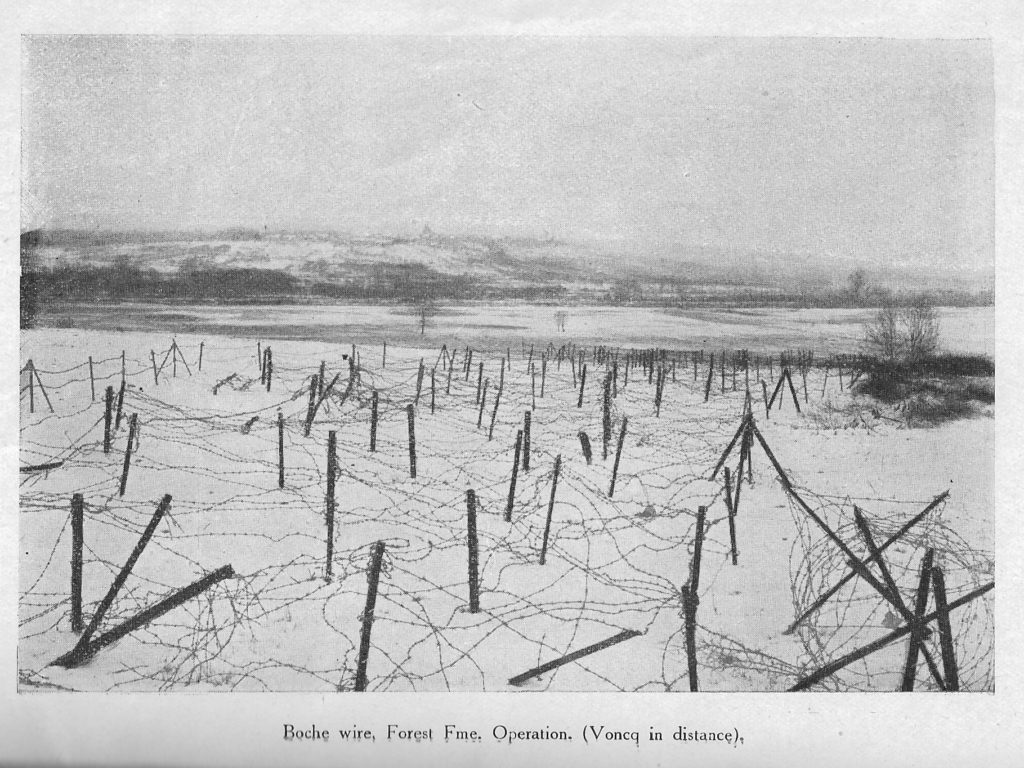

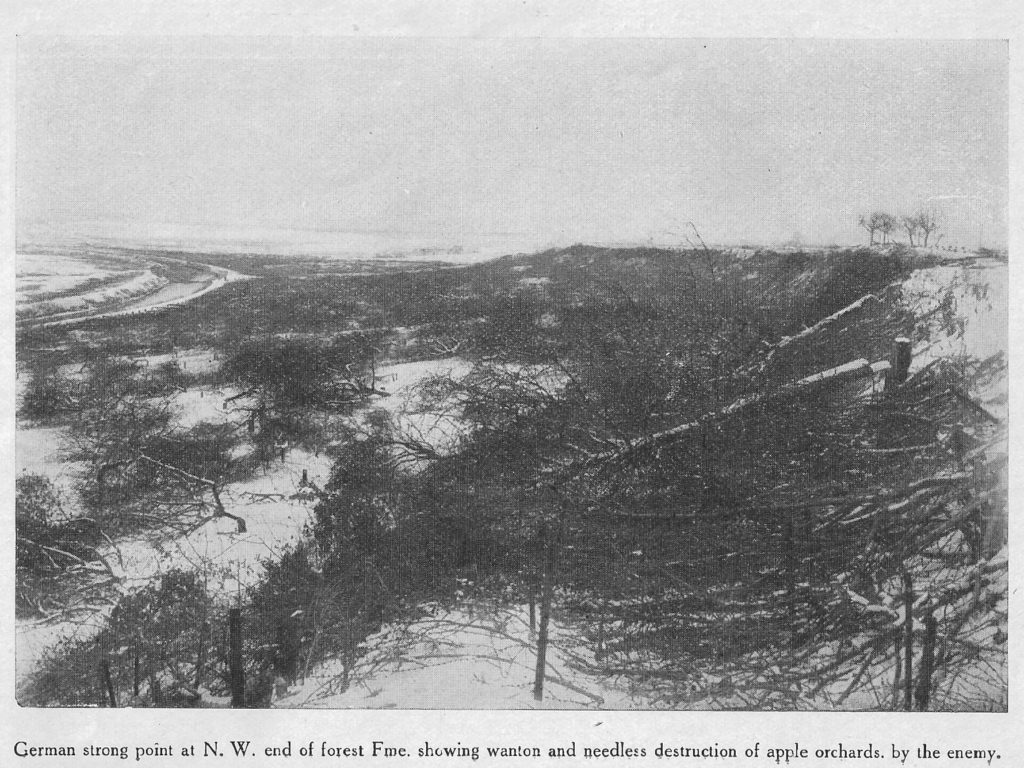

The German position was well defended. They had cut down trees to improve their field of fire around the hilltop on the south side of the Aisne. Three bands of barbed wire, each about twenty feet thick separated them from the Allies. A trench line ran most of the way across the German outpost, which was located on a U-shaped area marked by a bend in the river. In addition to the trench, there were concrete bunkers and some cannon. More than thirty machine guns defended the hilltop. Across the river, German artillery could hit any spot for miles around.

On October 23rd, the 71st Brigade was formally ordered to take the hill, known as Forêt-Ferme, or “Forest Farm”. It was to be their last action on the Champagne front before their relief. As a result, leaders of all the units devoted themselves to preparing.

Making preparations

Bitter experience was the reason for their hard work now. Two weeks before, the 71st Brigade went into battle with next to no preparation and endured horrendous casualties. Firstly, there was scant advance warning of the attack. In addition, artillery was mostly ineffective, and French tank support was a disaster. That they succeeded at all on October 8-10 was because, as U.S. Marine private Elton Macklin (who was there) observed,

“They were green untried troops who charged in reckless ignorance and won. They paid a price in taking Saint-Étienne.”

Therefore maps were copied and passed around. Company commanders instructed their platoon leaders. Each soldier knew his job and the job of the guy next to him. Weapons like the Browning Automatic Rifle were given to men in the first wave. Soldiers in the outpost holes kept close watch on the Germans, some of whom were just sixty yards away.

Preparing the way for the attack was the artillery. The U.S. 2nd Artillery Brigade had every foot of Forêt-Ferme dialed in. French artillery was on hand to harass German artillery across the river. When the attack began, many targets would be shelled. As a result, the Germans would not be sure of the real objective. In addition, the Brigade’s Mortar Battery was moved into the trenches near the front line. Men from the U.S. 2nd Engineers with large wire cutters embedded with each of the assault battalions.

Standoff

As preparations were made, opposing forces were still locked in a standoff along the river. German artillery strikes just opposite Forêt-Ferme increased when the Americans replaced the French there. As a result, American gunners in the 2nd Artillery, using captured German cannon, sent over the gas shells the Germans left behind. Incensed at being given a dose of their own medicine, the Germans lobbed shell after shell of mustard gas on the Americans on October 26th. The Americans were by this point experienced in gas warfare. Clouds of the yellowish gas in open fields could be avoided. The chemical, which spread after the explosion and penetrated clothes before turning into a gas, was more dangerous. The Germans sent over so many gas shells that villages near the front were spattered with the orange-yellow chemical.

Waiting

On October 27th, Americans were withdrawn from their listening posts. They would be too close to the Germans once the attack began. The day was sunny and clear. Assault troops had moved forward into the front line before sunrise that day. Throughout the 27th they remained there, lying still and waiting. German positions were closely watched, looking for any changes in their routine. There were none. In the late afternoon, five German planes flew over American lines. Nothing they saw caused alarm.

Four o’clock, and it started to grow dark over the Aisne river valley. Still nothing changed. If the Germans were paying attention, they might have noticed that the observation balloon opposite Forêt-Ferme was not reeled in, as it had been every day, promptly at 4:05 p.m.

At 4:10 p.m. a single cannon fired from the Allied side. It signaled the beginning of a devastating barrage into the German position. Artillery shells hit all along the German side of the river. Smoke shells made a black curtain around the bend in the river. The mortar battery started firing. French artillery pounded German observation posts on the hills across from Forêt-Ferme. German artillery opened on the Allies but, for once, it was scattered and ineffective.

Attack

At 4:30 p.m. the American barrage shifted forward, and Americans were out of their trenches. Engineers with wire cutters in their hands and rifles slung on their backs crawled forward. They worked on cutting strands of barbed wire while soldiers crept forward. American machine guns kept up fire just above the heads of assaulting troops.

American soldiers cleared the first belt of wire. German machine guns were silent, their crews dead or hiding in bunkers. Smoke screens kept German artillery from firing accurately. As the assault wave reached the second belt of wire, follow-up troops were already advancing behind them.

Artillery was still falling on the German main line. American soldiers, keeping their space, were advancing just out of range of the explosives. Men moved forward as a unit and did not lose formation. Likewise, the support wave kept its distance from the assault wave. It may have looked like an exercise, but it was no exercise. German shells were hitting the battlefield. Some men in the 142nd Infantry were hit by American shells that inexplicably fell short while they left their foxholes.

Moving up the hill

Meanwhile, the second belt of barbed wire was crossed. American machine gunners kept firing over the heads of the assaulting wave. In addition, American shells were pounding the main German line as they advanced. Lieutenant Ben Chastaine remarked they were practically “leaning against it” when the assault troops crossed the last barrier before the German trench line. The barrage moved forward.

With bayonets fixed and grenades at the ready, men of the 71st Brigade leapt into the trenches. Fire teams moved through the maze, searching every corner. Machine gun teams carried their weapons forward through the wire barriers to set up closer to the concrete bunkers at the top. Meanwhile, assault troops carefully made their way through the trenches to the bunker exits, while others moved past to other objectives.

German soldiers exited the bunkers expecting to return to the trenches when instead they stared down rifle barrels. Immediately, they lifted their hands and called out, “Kamerad!” They were caught completely by surprise. Some German machine gun nests behind the main line fired on the attackers, but these were surrounded and silenced in short order.

Exploitation

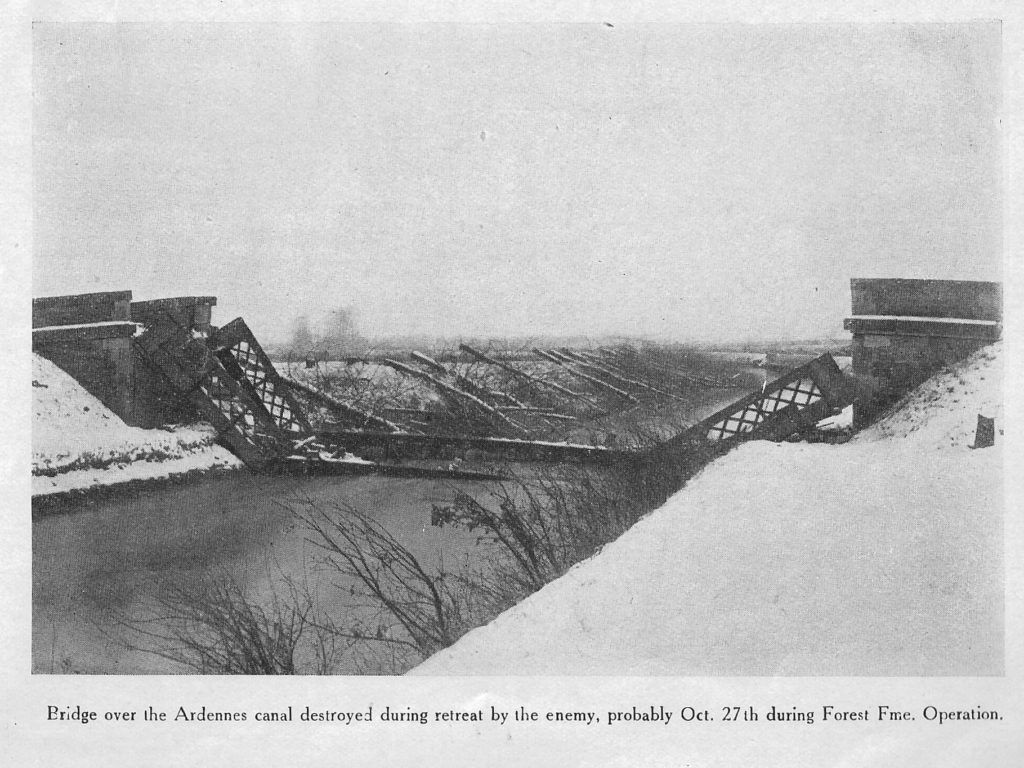

As instructed, American patrols advanced past the dugouts toward the village of Rilly-aux-Oies and the river. They found no Germans there, but discovered the bridge over the Aisne had been blown. Patrols combed the riverside for stragglers and brought back twenty-seven prisoners.

German artillery reaching the hill was infrequent and inaccurate, thanks to the smoke screens. Teams of American soldiers were clearing out the last of the bunkers, and one soldier wrote that:

“The first Germans I saw were coming out of a dugout yelling ‘Kamerad’ at every breath, so I picked up a few German hand grenades, which we call potato mashers, and when I come to a dug-out would pull the string and throw a couple in. If any one was at home, they had a hard day.”

As the last of the bunkers was being cleared a German runner made a break down the hill toward Rilly. The battalion intelligence officer had a shotgun and winged him, and he was made prisoner. His documents were very helpful at Brigade Headquarters.

Aftermath

The Americans had been up against a battalion of the 9th Colberg Grenadier Regiment, part of the 3rd Prussian Guards Division. They were considered a first-rate outfit, but the men in American custody seemed relieved to have been captured.

Not so lucky were their commanding officer and the artillery officer, dead along with nearly fifty other defenders. Moreover, one hundred ninety-four Germans were captured. The battalion was smashed.

American losses were fourteen killed and thirty-six wounded. National Guard troops from the Southwest had met a well protected enemy and routed him. Four of the German prisoners were officers. After interrogation, they were asked if they had anything to say. One spoke up and wanted to know, “What nationality were the telephone men?”

(Read more about Native American code talkers here.)

My Great Grandmother’s brother, Walter Lee White, from Comanche, Texas, was a member of Company K of the 142nd. He survived but died in the Big Spring, Texas, VA hospital in 1960. I have very much appreciated your work on this great and detailed summary of what happened to this group of Texas National Guardsmen.

My Great Grandfather, Emmit Parrish, was a Sergeant in the 36th Division, 142nd infantry. Originally from Wolfe City, TX, he was wounded during the war, but I am not certain where. He passed away in 1980, but even as a little kid, I remember him having night terrors up until the end of his life. It’s been incredibly difficult to find information on their journey to and from the states. Thank you so much for this article. Great work. I have a small journal he briefly kept, his mess kit, and a couple photos, one of the 142nd, I think it might say Company F, although I am not completely certain, and one of what I think are the NCOs. I’d be happy to share if anyone is interested in seeing them

Hey Jason thanks for writing. Emmit Parrish was a Private in I Company, 142nd. Infantry. This whole blog, 60+ pages, tells the story of the 142nd. from its inception in 1917 to inactivation in 1919. Better yet, the National Archives has your Great-Grandfather’s letter, in his own handwriting, online. Here it is: https://catalog.archives.gov/id/77426021

Thanks for the reply. I did find the letter, that’s pretty amazing to see. It has him listed as a Private, but at some point he was promoted, everything we have on him was as a Sergeant, it’s even on his gravestone. I sure appreciate the information you provided!

Hey Jason,

You’re right: Sergeant Emmit Parrish Service Record

Wow, and the card lists no injuries. That’s interesting, when my grandmother told me about him later in life, she must have been wrong about him being injured. It says no injuries. I can’t thank you enough for your help, this has been a gold mine.