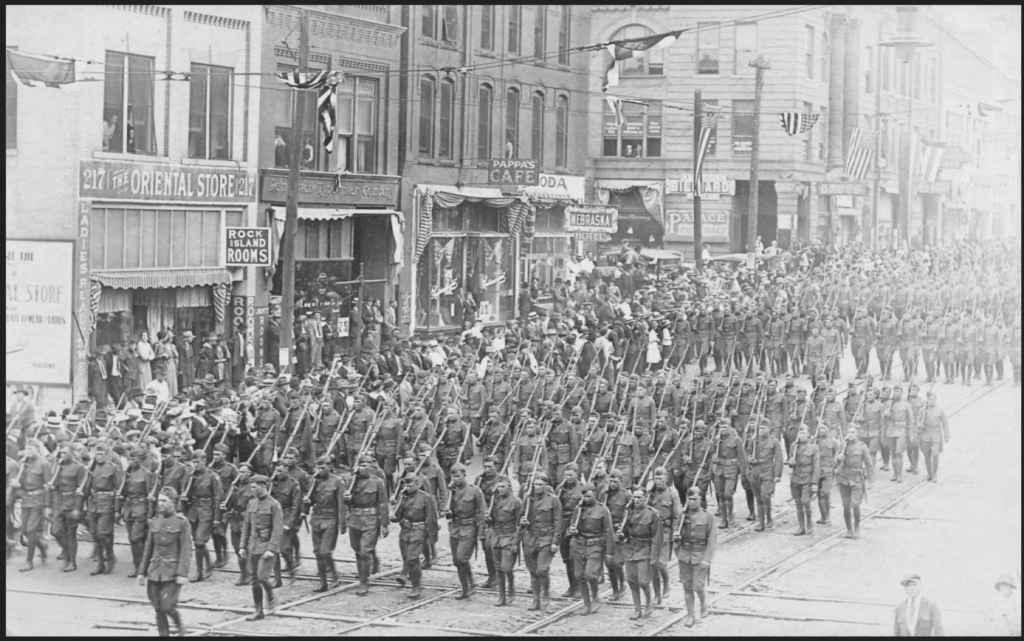

Otho Farrell likely returned to Amarillo on June 18, 1919; the same day as most of the men of Potter County’s Company G. He had a couple months’ back pay and his sixty-dollar bonus in his pocket. Fortunately for O.K. Farrell, he could return to his old job at the Santa Fe Railroad. When he enlisted, he had been a stenographer in the Superintendent’s office at the Amarillo branch headquarters.

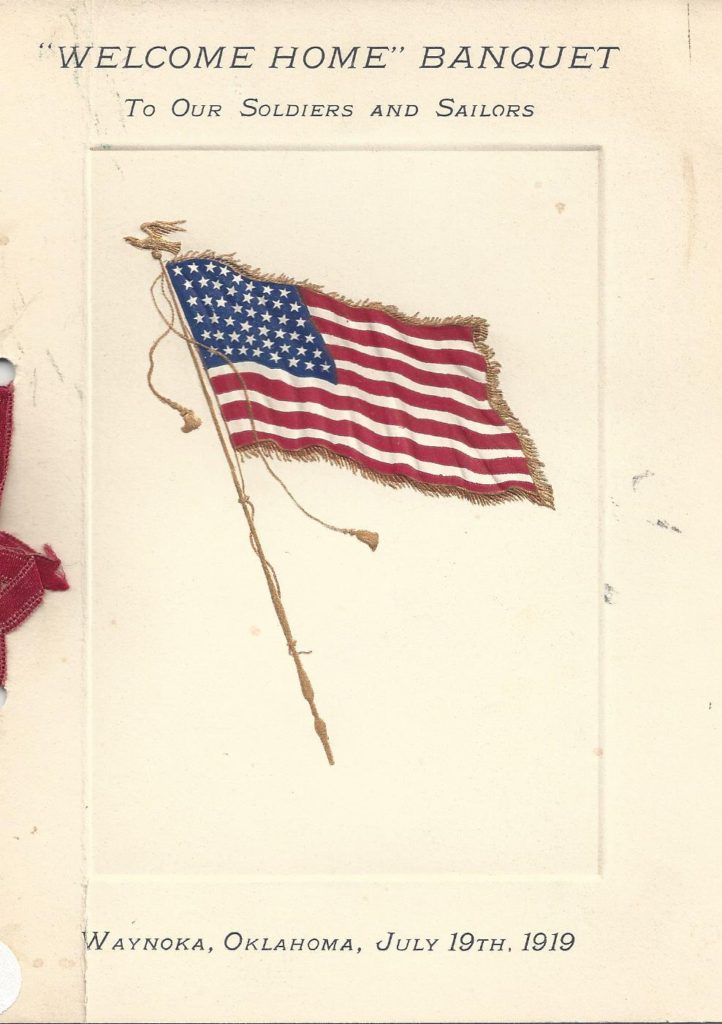

Sooner rather than later, Otho would see his family in Waynoka, OK. His parents and two sisters lived in this small town, over two hundred miles from Amarillo. They had not seen him in over a year. That summer, on July 19, Waynoka had a banquet for its Great War veterans. Otho’s family very much wanted him to make the trip to attend. However Otho seemed ambivalent about attending. Like many veterans, he had experienced life in the military and was now ready to move on. Anyway, the program for that banquet has been kept, so it’s likely he did go.

Victory Medal

In 1920 the War Department began issuing the Victory Medal. The medal was authorized in April 1919 and everyone in uniform from April 1917 to November 1918 was eligible to wear it. 4,412,533 men and women served in the armed forces during this time. However only about half this number served overseas. The Army began issuing their version of the Victory Medal in June 1920. Most soldiers had already left the Army by that time. To get one, a veteran had to fill out an application and have it endorsed by a serving officer before mailing it to the Army. Two and a half million Victory Medals were distributed. Soldiers of the 36th Infantry Division were entitled to wear the “Meuse-Argonne” and “Defensive Sector” battle clasps. (Read more about the battle clasps here)

A courtship

Meanwhile, what about Gladys Loper, that girl Otho wrote home to? During the time Otho was in the army, Gladys graduated high school and attended teacher’s college. She had grown up. Both Otho and Gladys realized that, despite frequent letter-writing, they did not know each other well. A proper courtship, carried over 213 miles’ distance, was begun. It took some time before Otho felt secure enough in his new job at the Treasurer’s office at Santa Fe. But in December 1920, Otho and Gladys were married.

The couple made their home in Amarillo, where they were active at the First Baptist Church. Otho served there as a deacon. He was also a member of the American Legion and its honor society, the “40-and-8s”. Otho served as Chef de Gare (Post President) of the Amarillo chapter of the 40-and-8s and kept up with his Company G buddies for the rest of his life.

Working at the railroad

Otho’s organizational skills, good humor, and hard work characterized him at Santa Fe as it did in the army. In his long career at Santa Fe, he was promoted paymaster and cashier on his way to the top. O.K. Farrell became treasurer and secretary of the executive board at the Amarillo branch in 1962. He had started at the railroad in 1914 as a message boy.

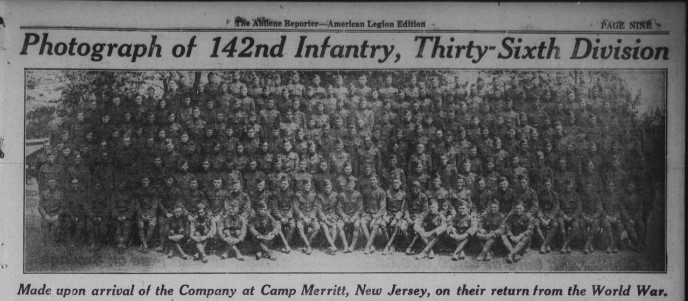

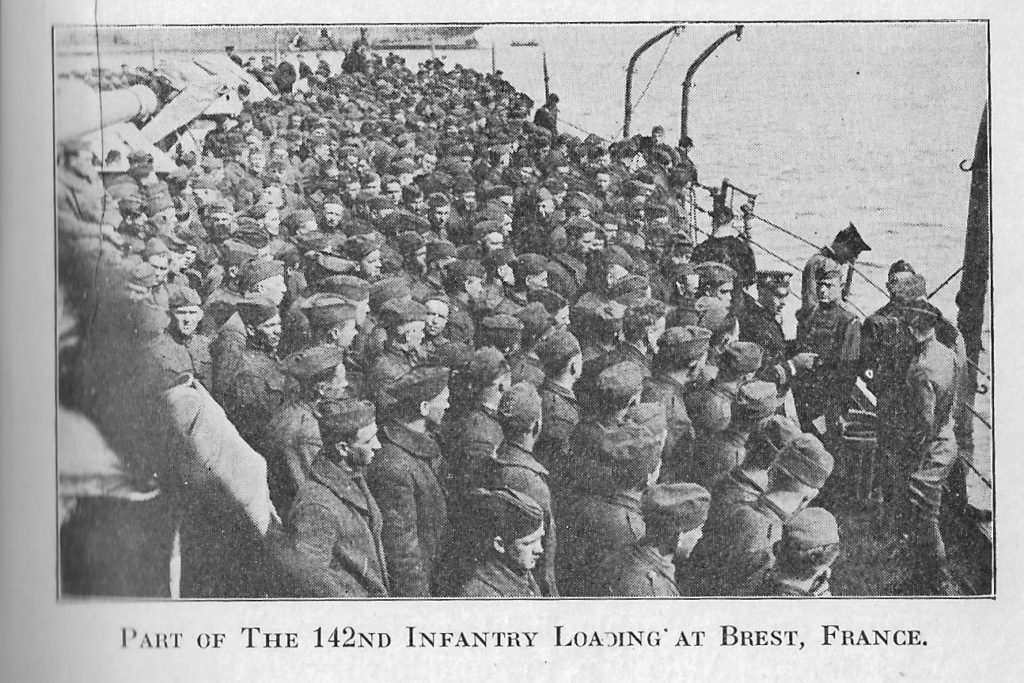

As a Santa Fe executive, he was able to ride the rails for free anywhere in North America. Santa Fe had a club car that executives could attach to its trains so they could travel in extreme comfort. The Farrells used this perk from time to time, but Otho was known for keeping careful watch on expenses. For example, it appears that after Otho returned to Hoboken, NJ with the 142nd Infantry in 1919, he never left the United States again.

He was OK with that.