“When Old Sol’s face does not appear/ Sometimes for most a half a year/

Go right on and grin and bear it/ When you’re home you can narrate/

How you adore, Old. Sunny. France.”

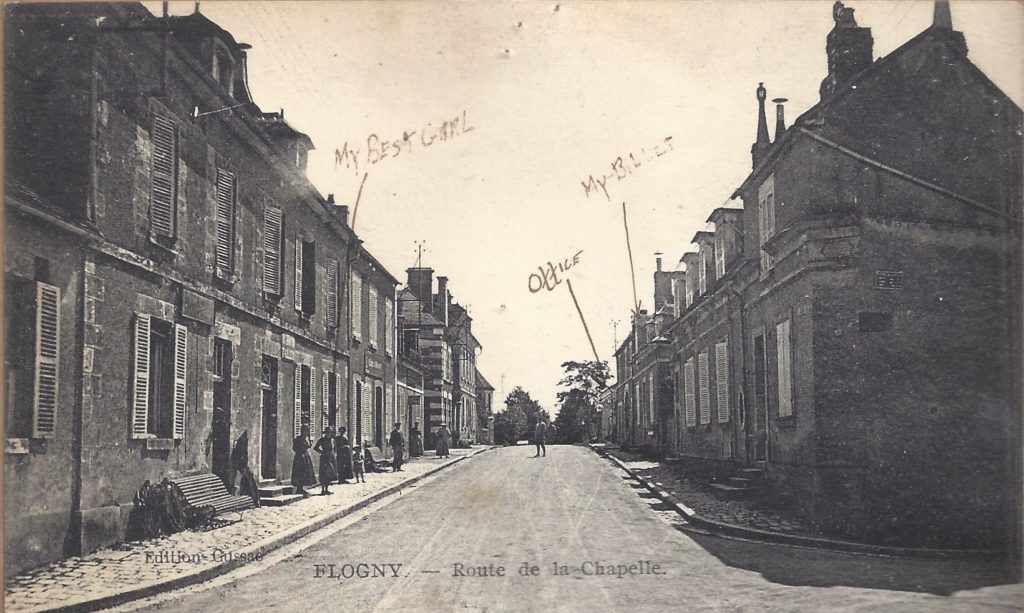

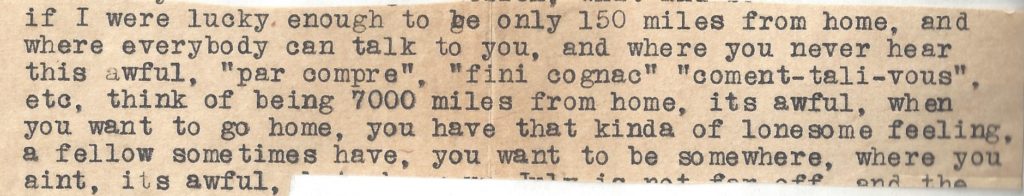

Private Barney Stacy, of Headquarters Company, 142nd Infantry wrote about conditions in northeast France while stationed near Flogny-la-Chapelle. His poem, “Old Sunny France” appeared in the April 4, 1919 edition of The Arrow Head. Now in their fifth month at the Sixteenth Training Area, men of the 36th Infantry Division were anxious to get home. The climate was not agreeable to the Southwesterners. In addition, the French were ready to get on with their peacetime lives. American soldiers frequently heard “pas comprend” (don’t understand) to routine requests they knew were understood by the French. Another thing that irked the Americans was that the price of things like bread, wine and cognac were higher for them. To top it off, the 78th Division, neighbors to the 36th, had just received orders to go home and were packing.

“Play Ball”

“Now that the spring of the year is almost in flower, the thoughts of young dough-boys turn to the one and only sport – baseball.” The Arrow Head, April 4, 1919

After the loss to the 89th Division in the American Expeditionary Forces Football championships, baseball promised to lift the men’s spirits. The number of baseball teams across the division outnumbered all other sports teams combined. For example, the 142nd Infantry Regiment had 70 teams. The gridiron laid out at Tonnerre was expertly repurposed into a diamond by two landscapers in the division, and a schedule was drawn up.

Not to be left out, the 36th Division as a whole had an All-Star team that was ready for the best in the AEF. Its players came from semi-pro leagues and collegiate programs from the Southwest and boasted a pitcher from the Chicago White Sox organization. The team was managed by Lieutenant Eddy Palmer, formerly of the Texas League, who also played second base.

Although many divisions had already shipped out of France by springtime, the 36th Arrow Heads did play the 6th Infantry Division in Tonnerre on April 16th, 1919 and won, 3-1. More changes in the AEF meant an end to Arrow Heads baseball after just one game, but the team had promise. (More about baseball in the AEF is found here.)

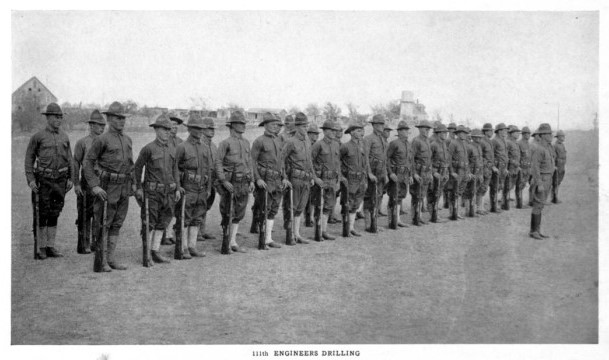

Know the drill

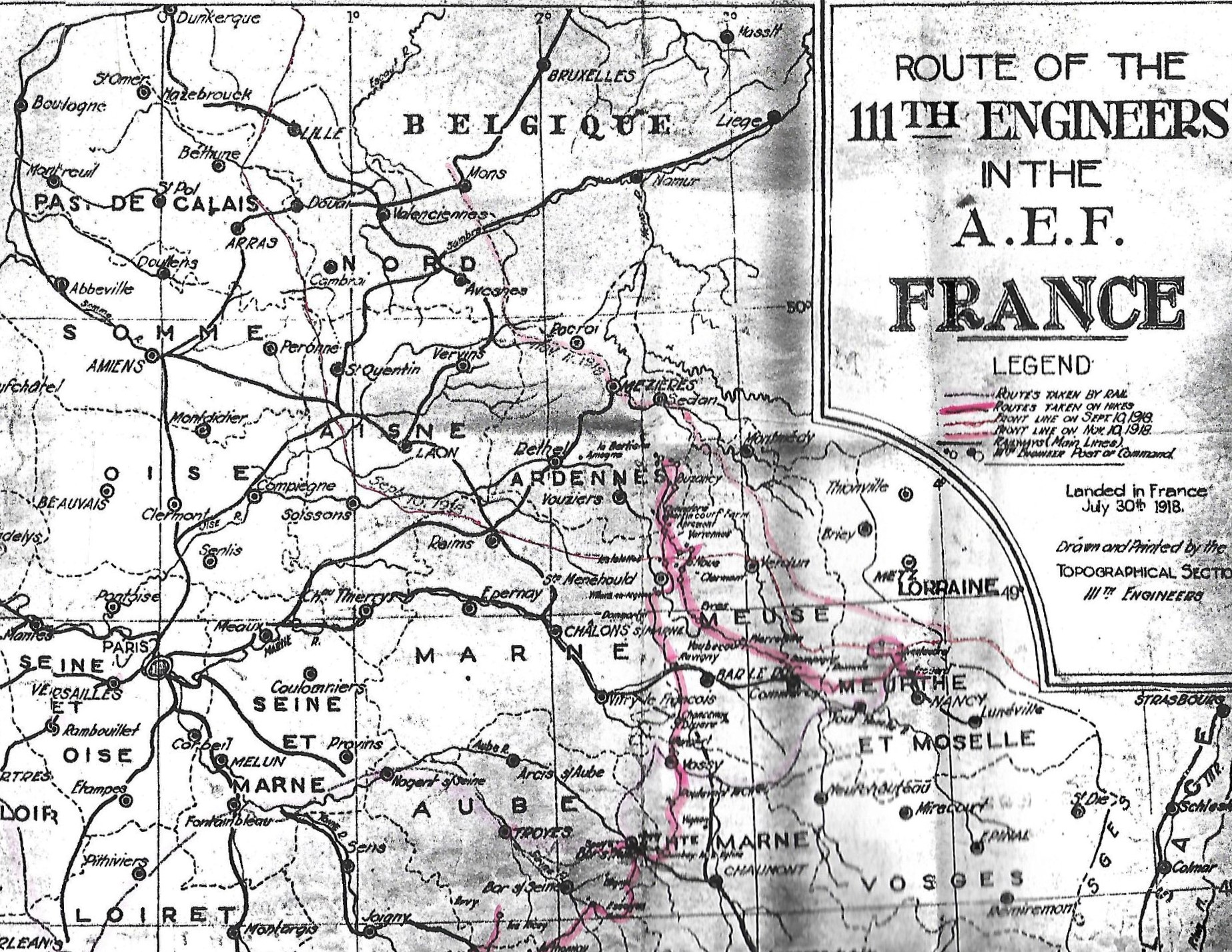

Another avenue to healthy competition in the AEF was in military skills. This was the Army, after all. Turning skills such as military drill, marksmanship, horsemanship, and maneuver into a sport did increase the participation of the soldiers. As a result, men of the 36th entered the arena with gusto. Company A, 142nd Infantry Regiment won the Close-Quarter Drill competition at the I Corps Military Tournament in Tonnerre. 1st Battalion, 143rd Infantry Regiment advanced to First Army Tournament in the Battalion Maneuver competition and came in second. Private Carl S. Kennedy of the 141st Infantry Regiment placed 10th in the entire AEF in marksmanship with his rifle. A two-man team from the 111th Engineer Regiment took first prize for horsemanship in wagon driving at First Army.

Literally old school

The most effective program in the AEF for soldiers waiting to go home was the schools program. It seems unbelievable today, but enlisted Americans in Europe attended Oxford University and the Sorbonne. Classes were established at nearly every level of command. For example, vocational skills such as welding and boilermaking were offered. Languages, literature and history were also popular subjects. Soldiers, sailors and marines attended at campuses from Ireland to Italy. With the added incentive of less work detail for students, schools in the AEF did a great deal to engage the men overseas. Schools also prepared them for the future at home as civilians.

A surprise visit

The most memorable event for men of the 36th Division was on April 9, 1919. The entire division assembled in a field in Melisey with field gear and shiny bayonets to be inspected by General Pershing. The Commander-in-Chief, AEF and his staff gave a characteristically thorough inspection, lasting several hours. A number of the men received their Distinguished Service Cross that day. In addition, the flags of the individual units were festooned with campaign ribbons by the general. The whole event took five hours.

While many of the men remembered the April chill and the rain of that afternoon in France, their time was worth the trouble. As with every division inspected, news came down from AEF Headquarters the next day that the 36th Division was to turn in their gear. They had orders to report to Le Mans for embarkation to the United States. The Arrow Heads were going home.