On June 13th, 1917, the cross-channel ferry entered the harbor of Boulonge-sur-Mer from England. On shore a young boy waved his arms, shouting “Vive l’Amérique” toward the incoming steamer. Though it was June, the tall, sturdily-erect man at the rail of the ship raised a gloved hand and waved to the boy, returning his greeting. The welcomes had just begun. Major General John J. Pershing was in France.

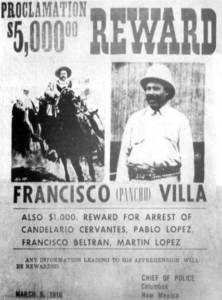

General “Black Jack” Pershing had been given command of American forces in Europe on May 10th. He had led men in combat in Cuba, the Philippines and Mexico; one of a few Americans of flag rank to do so. He was in France to build an American army that would match the French and British armies in size and professionalism, if not in experience. With him on the steamer were his military staff of about 40 officers, some civilian employees of the federal government, about one hundred enlisted soldiers and his adjutant, Captain George S. Patton.

The first American wave into France totaled about 190 men.

(Read more about General Pershing’s arrival here)

Dark days for France

The welcome of the French was out of proportion to the size of the American advance guard. France had been in the war for nearly three years and had been bled white by the costly offensives and attrition of the Great War. French line units were deeply demoralized by the spring of 1917 and some of them had mutinied. Dozens of mutineers had been court-martialed and shot. The Americans’ arrival at this crucial time restored the spirits of all France.

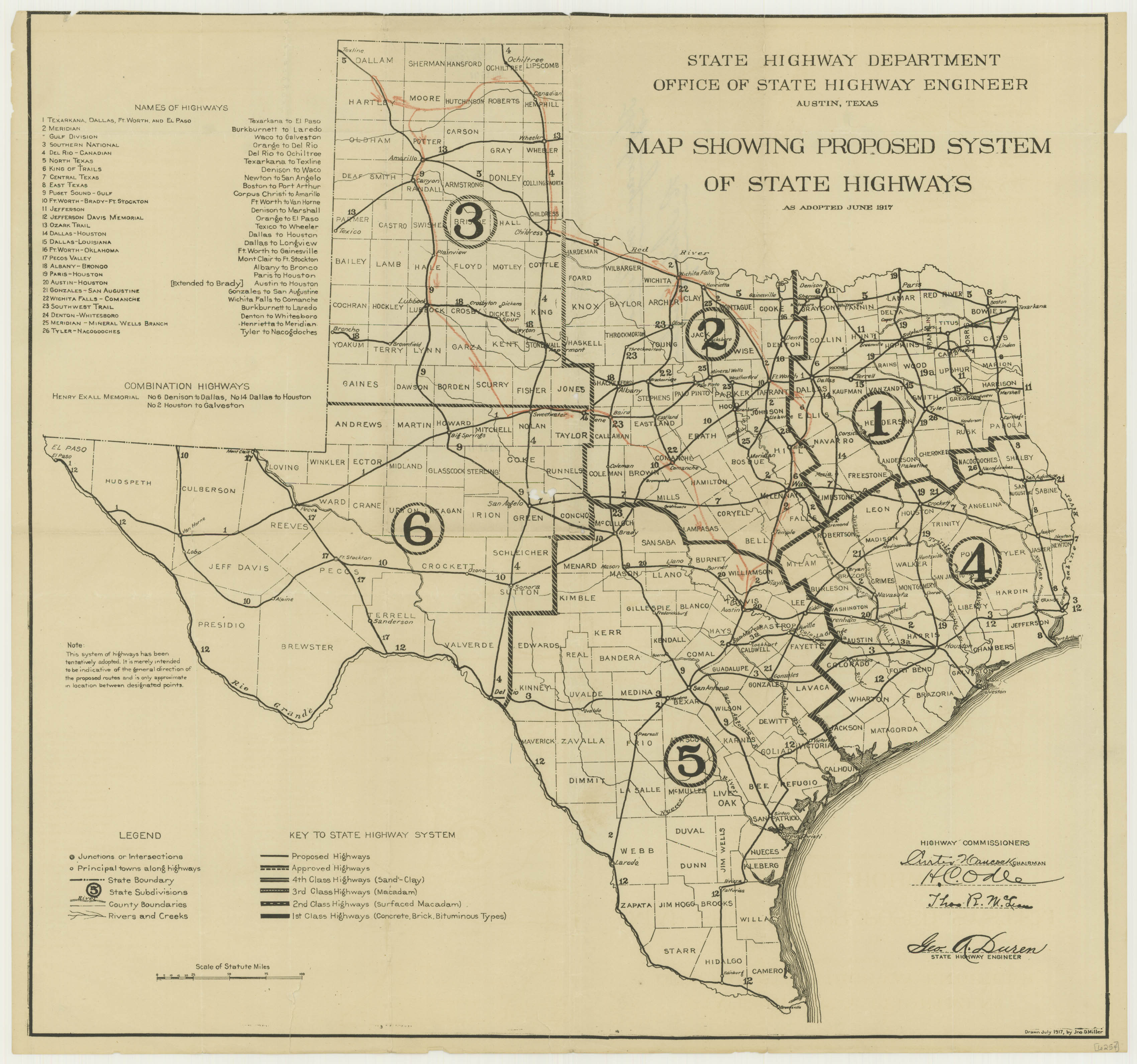

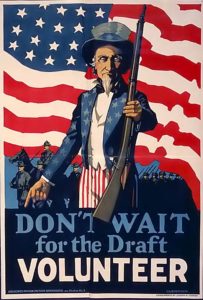

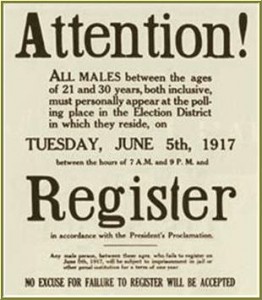

Pershing’s small staff had their work cut out for them. The American Expeditionary Forces, as they were now known, planned to bring an army of one million men across the Atlantic to fight. To accomplish this, they would have to build infrastructure: docks, roads and railroads. Incoming soldiers would need training camps, supply depots and field hospitals. They needed tons of food, fuel and clothing. As this was the early Twentieth Century, they would need horses and fodder to feed them. And weapons; no one at AEF Headquarters was sure what weapons the American Doughboy was going to use in combat.

The key to this and all other problems lay in transport. The United States had limited transatlantic shipping capacity and too many men, animals and materiél stateside. French and British generals were insistent that America send troops, but Napoléon’s rule that an army marches on its stomach had to be followed.

The vast Atlantic

Bringing the American military in force to Europe in time to defeat Germany would require the Allies had mastery of the seas. They didn’t. German submarines had resumed unrestricted attacks around the British Isles in February 1917. Britain was fearful that losses on land and sea may end the war in Germany’s favor before the United States could fully enter it.

In the early evening of April 24th, six U.S. Navy destroyers cleared Boston harbor steaming east. Their mission would become clear only when they were fifty miles east of Provincetown. Once out to sea, the orders read that they were to cross the Atlantic and make contact with a British warship outside Queenstown, Ireland. The U.S. Navy was going to war.

The six ships of Destroyer Division Eight arrived in Ireland on May 4th, 1917. Their home base was Queenstown (now Cobh), on the south coast. They began patrolling the Western Approaches of the British Isles almost immediately and were joined by another six American destroyers on May 17.

Antisubmarine patrol from Queenstown was not glamorous. The coastline was unfamiliar; filled with dangerous rocks and ledges. The weather was notoriously bad year round. German submarines were laying mines and stalking ships. American destroyermen had to learn how to track submarines from the men of the Royal Navy, who’d been at it for over two years.

The Return of the Mayflower, 4th May, 1917 by Bernard Emmanuel Finnigan Gribble

A debt repaid

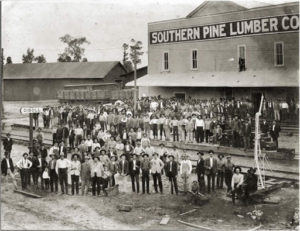

Slowly, the number of American soldiers in France grew. By the end of June, about half of the U.S. First Division, the Big Red One, had landed in St. Nazaire. There was also a battalion of U.S. Marines. American soldiers and marines were enthusiastically greeted everywhere they went.

Pershing knew they were not yet ready for action. They would need to train for the relentless trench warfare of the Western Front. Also, they would need to train with new and unfamiliar weapons and tactics. Most of all, more men were needed in France.

July 4th, 1917 saw a parade in Paris. For five miles through the old city the 2nd Battalion of the 16th U.S. Infantry Regiment marched until they reached the gravesite of Marie-Joseph Paul Roch Yves Gilbert du Motier, the sixth Marquis de Lafayette. With General John Pershing at the head, the Americans saluted their Revolutionary War comrade. A voice called out “Nous voilà, Lafayette!”