The 65th Congress hit the ground running. It had gone into session early; one day after Inauguration Day, March 4th. (January inaugurations did not take place until 1937.) President Wilson had already spoken to the Congress twice in March 1917 to ask it to arm U.S. Merchant vessels against German submarines. Such action had become necessary after Germany announced on January 31 it would once again target neutral ships approaching the British Isles or France.

Germany Reaches Out to Mexico

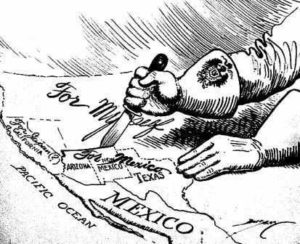

The Congress already had a full plate. On February 28th, American newspapers printed the Zimmermann telegram. (You can read it here.) The telegram had been sent in code from Berlin on January 19th. Its author, Arthur Zimmermann, was the German Foreign Minister. In it he instructed his ambassador in Mexico City to encourage Mexico to attack the Southwestern United States. However, this was only to be if the U.S. declared war against Germany. Finally, Germany would repay the favor by financing Mexico’s war of reconquest and sending arms.

The interception, decoding and publication of the telegram is a spy story only Ian Fleming could write if it hadn’t really happened. Consequently, it created a firestorm in America. Relations with Mexico could not have been worse in 1917. A sizable U.S. force had just returned from an eleven-month long incursion that took it 400 miles into Mexico. They were seeking to capture revolutionary and bandit Pancho Villa. Villa and his men had raided border towns in Texas, New Mexico and Arizona. For example, he attacked Columbus, New Mexico on March 6th, 1916.

The U.S. expedition, led by then Brigadier General John J. Pershing, failed to apprehend Villa. As a result, the entire Southwest was on edge. National Guard units were posted there to meet the threat. The U.S.-Mexico border was becoming militarized.

Suspected Sabotage

The rest of the country, though officially at peace, did not escape violence. On July 30th, 1916 the Black Tom munitions depot in Jersey City exploded. The huge blast damaged the nearby Statue of Liberty and shattered windows in Times Square in Manhattan. Although it was not immediately clear who detonated 100,000 pounds of TNT at Black Tom, the explosion was deliberate. As a result, Americans feared foreign spies, but were already looking to their immigrant neighbors with suspicion.

The hidden hand of sabotage apparently struck again on January 11, 1917 when a munitions factory in present-day Lyndhurst, New Jersey exploded. By the time President Woodrow Wilson asked a special joint session of Congress for a declaration of war against the German empire on April 2, many Americans felt as if the war had already come to them.

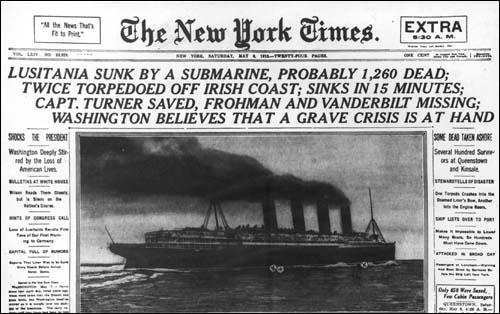

What was in 1914 an overwhelmingly neutral American public had in thirty months changed to decidedly pro-war. Fears of hostile saboteurs, a potentially disloyal immigrant population from Middle Europe had many on edge. Furthermore, the loss of Americans aboard the Lusitania had changed public opinion against Germany. Finally, the revelation of the Zimmermann telegram changed things materially. The possibility of Imperial German bases on the Gulf shore of Mexico and Imperial Japanese bases on the Pacific shore, however remote, had made this far-off war a near thing indeed.

War Declared

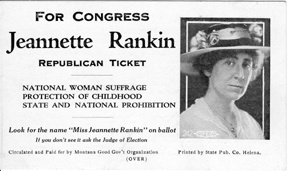

The U.S. Senate voted for war on April 4th, with 82 votes in favor. After that the House followed in the early hours on April 6th, with 350 members voting for war against Germany. The threat, even the reality, of hostilities with powers orchestrated by Germany had moved the United States into war. Similarly, some Americans responded to President Wilson’s appeal to a “peace without victory”. More accurately, he appealed to a victory of law, human rights and democracy over aggression, tyranny and empire. It was a significant and fateful moment in the American experiment. (More from journalist David Smith in today’s edition of The Guardian here)

P.S. The telegram the United States didn’t get? The one from Mexico explaining that German telegram…