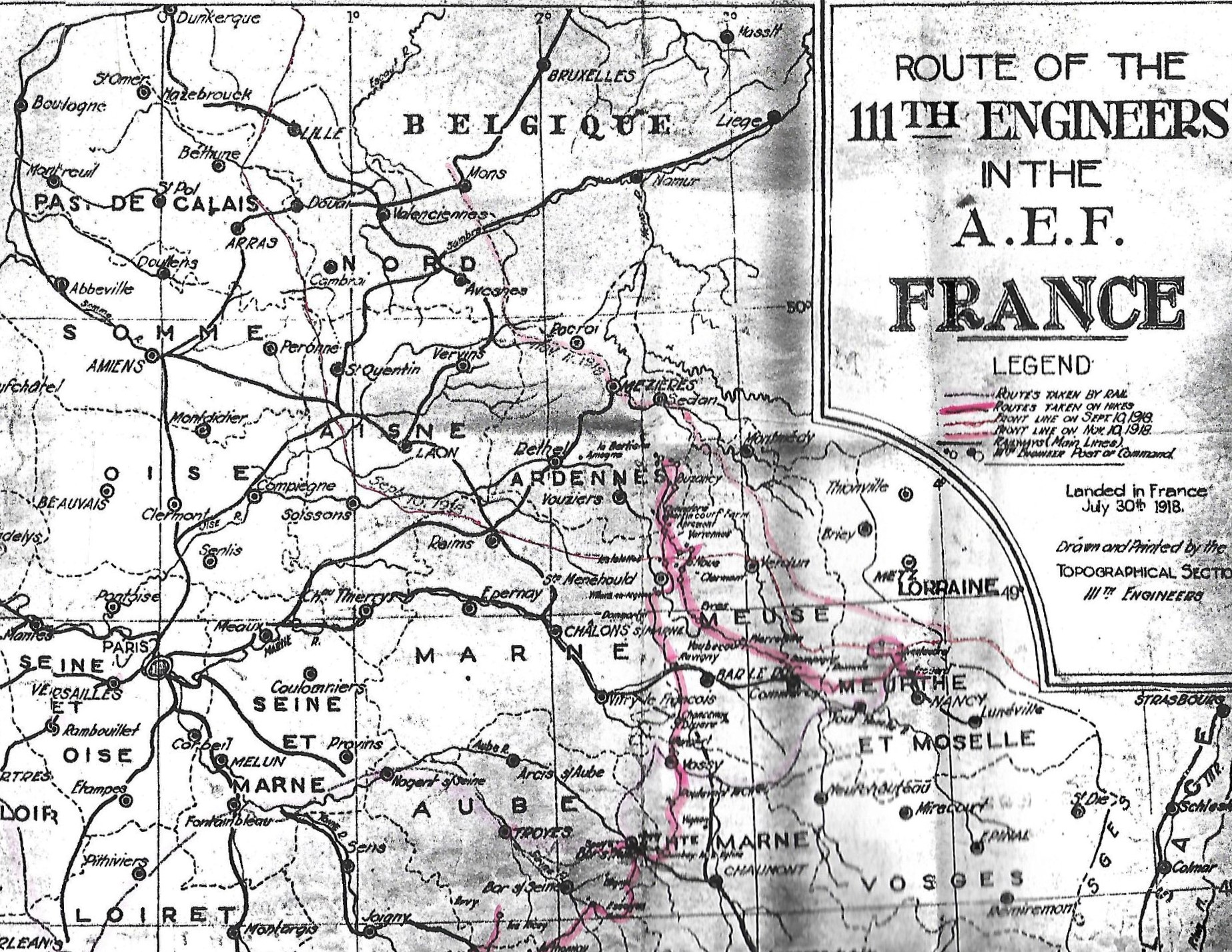

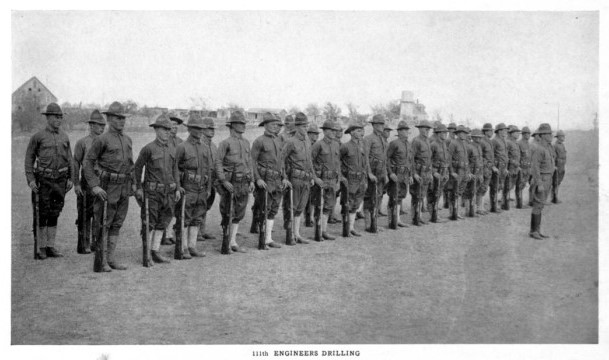

The 111th Engineer Regiment was part of a National Guard Division, the 36th Infantry, that was sent to France in July 1918. Six weeks after they got there, the 111th Engineers were sent to the front without the 36th Division. For the rest of the war they served as the Engineers of I Corps, First Army. Their job was to follow closely behind the leading division of the First Army and clear obstacles, defuse landmines, build roads and string telephone wire along the front. Their job would have been difficult even if it were not in the combat zone. Clearing mines and building roads so the wounded could be transported to hospitals saved a lot of lives, but the job was dangerous.

September 23, 1918 found the 111th near Les Islettes in the Argonne Forest. They were close to the front line and still with I Corps, American First Army. They had spent the last seven days on the march to get to the Argonne Forest, where the largest American operation of the war was about to begin. As usual, it was raining. The men found shelter wherever they could. The area was full of American and French forces moving forward, preparing for the coming fight.

Meuse-Argonne

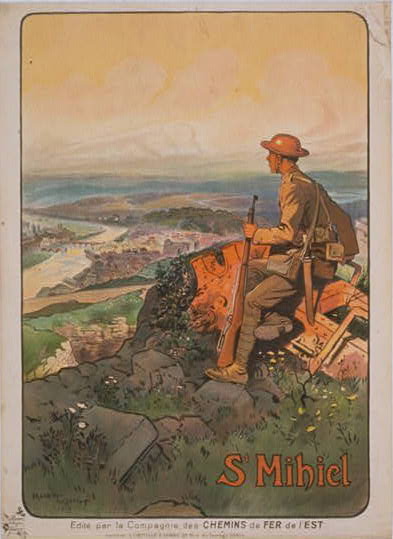

On September 25th, the 111th Engineers were on the move again, marching at night once more. Around midnight hundreds of American and French cannon begin firing at the Germans and the battle is begun. By 5 a.m. on the 26th, the Engineers are on the road again marching through Clermont-en-Argonne and Neuvilly-en-Argonne in heavy rain. German artillery hit their position in Neuvilly at 10 a.m. and they spent the day repairing the road. The next day the 111th is at work further up the road between Boureuilles and Cheppy. German prisoners and wounded men on their way from the front fill the road. German artillery continues to fall, but Americans are still advancing.

The 111th arrives in Varennes-en-Argonne on the 28th to find the town demolished by the fighting. German aircraft once again are bombing at night. Artillery projectiles are falling all around, in one instance killing a number of soldiers near the 111th Engineers. On the 29th, Company D enters Vauqois, a small village that was the front line on the first day of the battle. It had been a battleground for four years. No living thing remained in Vauqois; artillery and tunnel mines from both sides cratered the countryside.

Stalled

By October 1, the gains of the first days of the Meuse-Argonne Offensive stalled. German forces had reorganized a defense just behind their front line, and the advances stopped. The 111th Engineers were in an unfamiliar situation: they hadn’t spent two nights in the same place for twenty days. The regiment was located near Varennes-en-Argonne at this time and there was plenty to be done. There were more roads to repair and since there was a bottleneck they were always crowded. The Engineers got to work and built a new road around Varennes to ease the traffic.

While American forces were making slow progress just ahead, German planes still ruled the air. On October 9th they bombed the 111th Engineers, killing one. They were also still in range of German artillery, which would send over shells for a few minutes and then go silent. On October 11th part of the regiment moved ahead fifteen kilometers to just south of Marcq and Grandpré repairing roads. It was raining there, too.

Doubling Down

With the advance stalled, American General John J. Pershing reorganized forces and sent new divisions to the front. The 111th were still near Varennes and trying to keep up. Rain was a constant; roads were turning into mud flats. Soldiers and supplies moving up toward the front, and wounded going away from it, kept the roads clogged. The engineers got in the habit of using rubble from ruined buildings in making roads, but more was needed. They found a quarry, and soon were hauling rock for their highways. They also cleared mines and improvised explosives buried in the roads by the Germans.

Through October the men of the 111th steadily built and rebuilt roads for I Corps north from Varennes. They even built a narrow-gauge railroad from their quarry in Chatel-Chéhéry. Through that month the American front line straightened and forces were better deployed at the front. By this point the First Army has overrun three German defensive lines in the Argonne region. German resistance was organized and determined. Their aircraft make frequent bomb sorties over the 111th, which make them a little nervous since some of them are encamped across the road from an ammunition dump.

November 1918

Just after midnight on November 1st, the 111th Engineers were on the move. At 3 a.m. they witnessed an artillery barrage that lit up the sky. “(T)alk about being able to read a newspaper at night,” one engineer wrote, “you sure could then.” One American Division, the 2nd Infantry, advances six miles the first day. The gains are costly and engineers encounter carnage on the battlefield as they make their way forward. The men are hard at work clearing the way for reinforcements. Once more, there are German prisoners streaming away from the fighting. In seven days the 111th had advanced twelve miles.

The retreating Germans blew up bridges, and shell holes dotted the roads. As the 111th repaired them, they saw abandoned trucks and artillery pieces. The enemy retreat was beginning to look hasty. The American advance brings the engineers further north. They are busy as ever, repairing roads, when Germany signs the Armistice on November 11th.

The men are hungry and exhausted. The 111th Engineer Regiment served 62 days in the combat zone, about three times as long as the rest of the 36th Division. On November 11th they began yet another long march, this time away from the front. Eventually they rejoined the 36th Division and waited until their transport back home. When they returned to the United States, they paraded in their hometowns of Tulsa and Dallas before the men mustered out of the Army at Camp Bowie in June, 1919.

After the war a motto was chosen for the 111th Engineers, Fortis et Fidelis. And that remains true of them to this day.

(You can read the account of Corporal Walter G. Sanders, Company B, 111th Engineers in Judy Duke’s post to WWI Texas History here.)