“You should hear some of the big shells whistle over. Makes you get ‘gully low.’” E.P. Taylor of Supply Company, 142nd Infantry, wrote to his family. He continued, “You good folks back home, no matter how many descriptions you read, can have no idea of the destruction and slaughter going on and of what an infantry man has to go through.”

On October 29, 1918, the 142nd Infantry Regiment marched away from the front line after twenty-three days in harm’s way. Buried where they fell were over 180 of their comrades, four unidentified. In addition, over six hundred wounded in the 142nd made their absence felt. Battalions looked like companies. The men wore the same clothes they entered the line wearing.

As they made their way back through the old battlefields, the 36th Division passed through the old Hindenburg Line, which the French captured at the beginning of the battle over four weeks ago. Before that, it had been the front line for over three years. James McCan wrote home, “We crossed what used to be the Hindenburg Line and such a sight I never saw before or since. There was not a tree or even a bunch of grass living for four miles across it.”

After spending the night at Camp Montpellier near Suippes, the 36th moved southeast toward the Argonne Forest, where an American-French group of armies was waging a colossal battle with the retreating Germans. However, the German armies would abandon a fortified line only to withdraw to another.

March to the Argonne

On October 30th, the 36th Division was on the march again and passed into control of the First American Army. In other words, they were no longer under French command. That day the division marched about fifteen miles and camped at Valmy. Moreover, the next day they marched eleven miles, to Dommartin-sur-Yevre, and took a day off. They were about to enter the Argonne Forest, the western boundary of the American battle zone. Two American armies and one French army were slowly advancing in this zone. John J. Pershing, Commanding General of American Forces, planned for his armies to seize important rail transport hubs behind German lines. If he succeeded, Germany would have to quit France and lose the war. (Read more about the Meuse-Argonne Offensive here.)

On November 2nd, the 36th entered the Argonne Forest, marching twelve miles to Les Charmontois. At this time, the division was passed from the American First Army to the Second Army, where they were assigned to VII Corps. The Second Army, with its six divisions, was going to attack in the direction of Metz, a fortified city and transportation center. As a result, the 36th Division was scheduled to leave for the front on November 11th, 1918.

While the marching was tough for the men, many of whom were still recovering, on November 3rd the 36th Division marched another fifteen miles. As they marched, they began to hear the distant roar of artillery fire again. Many of them arrived at their destination that day. That is to say, at the villages near Bar-le-Duc, just back of the front lines. In seven days of marching, the 36th Division had traveled over seventy-eight miles.

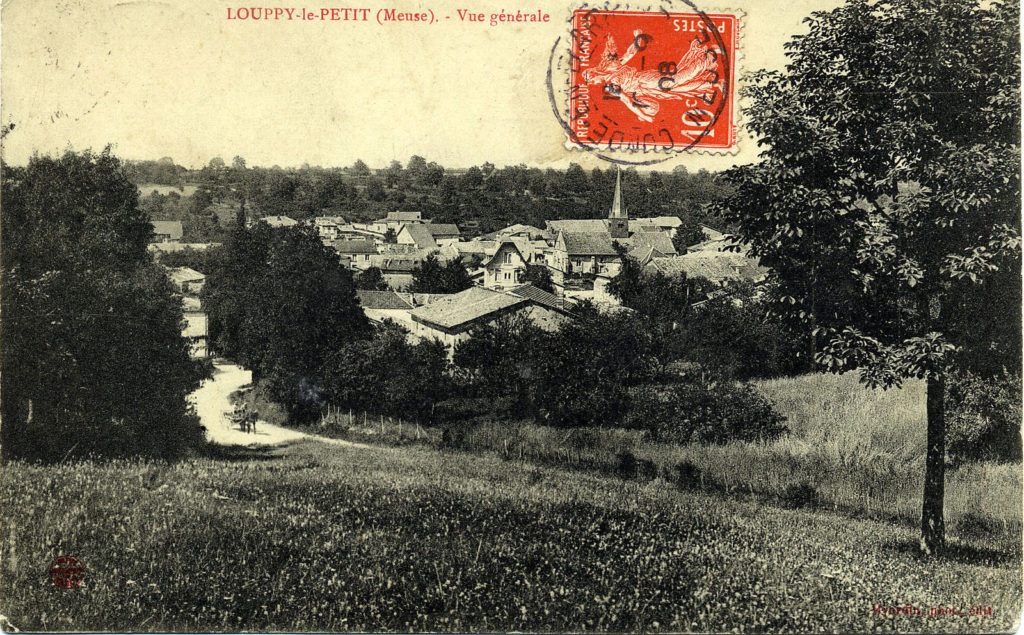

Louppy-le-Petit

The division was allowed two days to rest. The 142nd Infantry Regiment was quartered in and around the tiny village of Louppy-le-Petit. The area around Bar-le-Duc was just recently vacated by the 1st Infantry Division, the ‘Big Red One’. The 1st Division had been in the fighting since day six of the Meuse-Argonne Offensive, and was recuperating around Bar-le-Duc after heavy losses. Now they were back in the battle; and the 36th Division would soon follow.

Replacement soldiers for the 36th Division were already arriving. Most of the replacements were from the 34th Infantry Division. The 34th was made up of National Guard units from Iowa, Minnesota and Nebraska, as well as North and South Dakota. These plainsmen trained at Camp Cody, New Mexico, and the Southwesterners of the 36th learned to like them. Moreover, the new men were well trained, and their morale was good.

Captain Ethan Simpson of H Company, wounded on October 8th near Saint-Étienne, returned to his men on November 4th. In addition, others returned to the 142nd from the hospital or from their assignments away from the battlefield. These officers and men, who had missed the fighting, were most eager to see the regiment back in action. However the rest of the men, who had seen it, were not as enthusiastic.

New uniforms and boots arrived. Consequently soldiers were able to change clothes, many of them for the first time in a month. What they took off wasn’t worth saving; so piles of old ruined clothing had to be trucked away. New weapons and equipment were arriving every day.

Training again

From November 6th the men were drilling again. Veterans of the Champagne front used best practices from combat to improve the training. They used every hour of daylight to train. But on November 7th came news that the German government was asking for a cease-fire. Many of the men didn’t believe it. The French people in Louppy-le-Petit sadly shook their heads, saying the war has been going on for over four years, how many times we have heard these rumors?

For six days the men trained and grew once again into a fighting force. More men were returning from the hospital. Soldiers were gaining confidence in their mission. The 36th Division was on track to be in the combat area once more on Thursday, November 14.

On Sunday, November 10th, the division paused to remember those who had died. There were memorial services in each unit, spread out as they were across the countryside. Soldiers in the 142nd stood in a solemn vigil as each of the names were read at the service. They had been away from combat for nearly two weeks now. But they knew they might return to battle. So the men took a moment to meditate on those desperate moments in battle and the loss of so many brothers in arms.

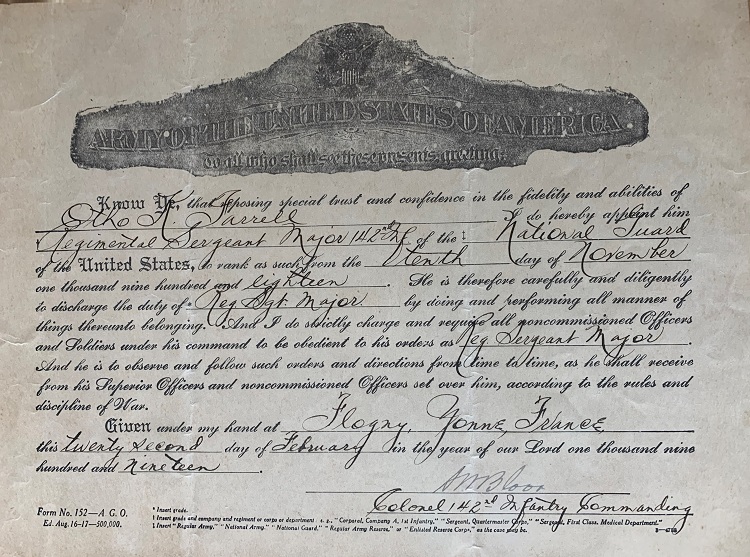

Promoted

On that same day, Color Sergeant O. K. Farrell of Headquarters Company was promoted three ranks to the highest enlisted rank in the army, Regimental Sergeant Major. As Color Sergeant, he led a small platoon of Headquarters men who ran the Regimental office. Since there were two Color Sergeants, they probably each worked twelve hours every day. Now O. K. Farrell was the ranking NCO at Headquarters Company. He’d just turned twenty-two when he was promoted.

It was an unlikely journey for the men of the 36th Infantry and for O. K. Farrell. Unlikely for the division that so soon they were combat veterans, now heading back into battle. Unlikely for Farrell, now promoted to the top. However, his superiors would have seen that he was superlatively well organized and hardworking. His job before the war in the Superintendent’s Office at the Santa Fe Railroad prepared him marvelously for administering a 24/7 operations nerve center of a fighting force. To end the war, Farrell and the 36th were ready to go the distance once more.