In October 1918 Allied forces and the German army faced each other in a tense standoff along the Aisne river in northeast France. Near the devastated towns of Attigny and Givry, the American 36th Division held the south side of the Aisne. The 36th was at the time part of the French Fourth Army. The French wanted to advance, but German defenses on the north side of the river were strong enough to give any attacker pause. There were rows of barbed wire and machine gun nests along the riverbank. Behind these defenses the Germans were building concrete bunkers and a trench system. Every day French and American troops received artillery hits from German long range guns; sometimes in the thousands.

In the meantime, the Germans had to be moved out of one outpost on the south side of the river.

Assault on the Loop

The Aisne river runs east – west through the Ardennes region of France until it reaches Attigny, where it curves around a hill and then runs to the southeast. On a map, the loop in the river looks like an inverted “U”. When the Germans retreated over the Aisne on October 12, they remained on this hill south of the river.

If the Fourth Army were going to get over the Aisne, it would have to first evict the Germans from the hill. Two attempts by the French 73rd Division resulted in minimal gains. As a result, the American 71st Infantry Brigade (141st and 142nd Infantry Regiments, plus the 132nd Machine Gun Battalion) moved in front of the loop on the night of October 22-23. The 71st began to plan their assault.

A communications problem

The best way to plan an assault is to keep the enemy in the dark about what you are about to do. This was difficult for the Americans because they were in a river valley with the Germans. Almost everything was in plain sight of the enemy. Even small movements during daylight would attract artillery fire. When Allied forces occupied the area, they reused the field telephone wires left behind by the Germans. Using the existing system saved time, but now commanders wondered if the Germans were listening in to their conversations.

American commanders tried a test: each regiment was given the location of a fictional ammunition dump over field telephone. In half an hour the location was pounded by German artillery. Now that they knew their field telephone communications were insecure, what was the solution? Messages carried by runners were slow and dangerous. Many runners became casualties in combat; and messages could take hours to arrive. As commanders in the 36th Division deliberated the answer, one captain at 142nd Infantry headquarters stepped outside to hear two men in HQ Company speaking in their native language, Choctaw. And he had an idea.

American Indians join the war

Oklahoma became the forty-sixth state in 1907. Decades before, what became Oklahoma was set aside by the Federal Government as Indian Territory. As late as 1890, one in four people living in Oklahoma Territory was Native American, about 65,000. Oklahoma still had a substantial Native American population by 1917. About two-thirds were U.S. citizens. The remaining one-third were citizens of one of over thirty tribal nations in Oklahoma.

When the United States entered World War I in April 1917, thousands of American Indians and Native Alaskans volunteered to serve. Many volunteers in Oklahoma joined the National Guard. This included both U.S. and non-U.S. citizens.

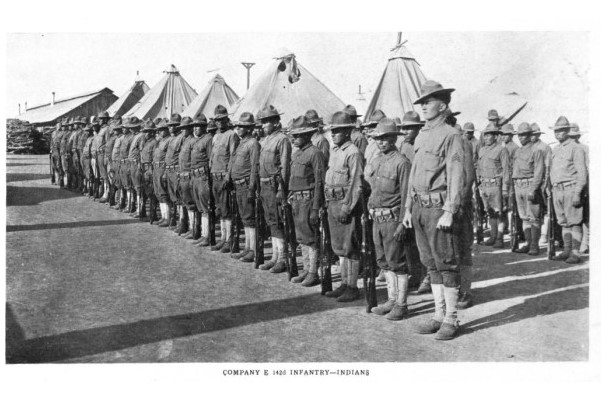

When the Oklahoma and Texas Guards merged into the 36th Infantry Division, several organizations in the 36th had multiple American Indians in the ranks. For example, E Company, 142nd Infantry was almost entirely American Indian; over 200 members. The reason for this was that the 142nd Infantry was itself a merger of a Texas unit and one from Oklahoma. Another Oklahoma outfit with several Native Americans as members was the 1st Squadron, Oklahoma Cavalry. The 1st Squadron became the 111th Ammunition Train when it joined the 36th Division.

About 12,500 American Indians and Native Alaskans served in American uniform in World War I. Though it is impossible to be exact, researchers and family members have now identified over six hundred American Indians who were members of the 36th Infantry Division at least for part of its World War I service. (See more about the effort to document their heritage here.)

Secure communications

While planning to attack the Germans, leaders in the 142nd Infantry developed the idea to carry out voice communications exclusively in Choctaw. Their commanding officer, Colonel A.W. Bloor, reasoned that “there was hardly one chance in a million that Fritz could translate these dialects.” Two American Indian officers of the 142nd Infantry, possibly Lieutenants Templeton Black and Ben Cloud, formed a group of “Code Talkers”.

Adapting their native language to the realities of Twentieth-Century warfare took some imagination and discipline. The men agreed that code for “regiment” would be “tribe”; similarly “machine gun” would be “little gun shoot fast”. Having worked out every military term they would likely encounter, the Code Talkers dispersed. In a very short period, there was a Code Talker at the phone in every command post from brigade to regiment to battalion to company levels.

It was time to test the plan in action. In preparation for the attack, it was necessary to move two companies of the 142nd Infantry closer to where the attack was to begin. The Germans were watchful; any clue from telephone intercepts could expose the operation. On the night of October 26th, 1918, two companies from 2nd Battalion slid out of their position and moved closer to the front. The Germans did not notice anything. After that, the Code Talkers would have to handle communications for a furious battle, just hours away.

Innovations in action changed the battlefield to the advantage of American Expeditionary Forces in 1918. Almost simultaneously, a number of American Indians used their skills as Code Talkers. These include men in the U.S. 3rd, 30th, 32nd, 36th and 90th Infantry Divisions in France. Their example would show the way to the World War II U.S. Marine Code Talkers.