In the predawn darkness of October 8th, 1918, Captain Thomas Barton hurried past soldiers and equipment to his place on the front line. The attack he was supposed to lead was to have started ten minutes ago. Barton, commanding G Company in the 142nd Infantry Regiment, had been in his commander’s post at 2nd Battalion Headquarters at 4:50 a.m. to receive his orders.

Just after five a.m. the Battalion commander arrived from Regiment Headquarters with the news: the 142nd was going on the attack along with their brigade that morning. The men would climb out of their foxholes and dugouts at 5:15. “Major, I cannot make it” Barton interjected, looking at his watch, “it is 5:11 now”. The major told his commanders to get to their companies as quickly as they could and pointed in the direction they should attack. The major had seen a map at Regiment, but he had no maps to give. Barton’s Company G and Company H would go over first, attacking in the direction of the village of Saint-Étienne à Arnes about a kilometer away.

Making war

In the costly and dense warfare of 1918 France and Belgium, the only way to advance was in carefully coordinated assaults of combined arms. That meant concentrated artillery barrages with the attackers already out of their trenches moving forward while shells struck the enemy just yards ahead. Moving with the infantry were tanks to take on rows and rows of barbed wire and machine gun nests. The artillery barrage would creep forward, and the attackers would rush in before defenders could organize. In addition, aircraft would spot the enemy strong points and signal coordinates by radio or handwritten messages for the artillery to strike. And the process would repeat.

At least that was the idea.

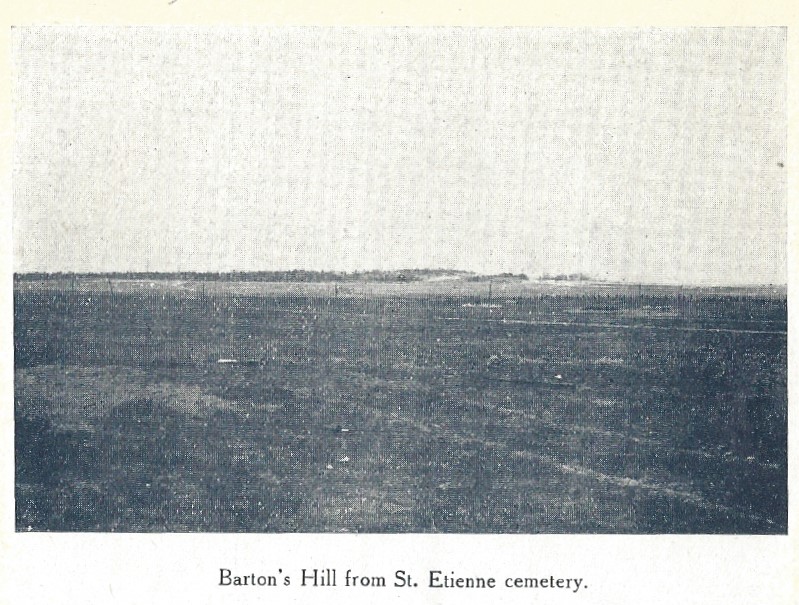

Captain Barton reached his men at 5:25 and explained the situation. Before them was gently rolling treeless farmland, punctuated with woods on low hilltops and around the village. The nearest German defenses were just one hundred yards away. They were concealed in a woods that stood between the American line and the village. From Barton’s position, he couldn’t see Saint- Étienne so the Major’s directive using the village as a reference point was not useful to him.

Thomas Dickson Barton had been a citizen soldier for twenty-six years. He’d been an officer, on and off, for over twenty years. He served in the Philippines during the Spanish-American War for over a year. He was on the Texas-Mexico Border for ten months as a company commander during the Crisis of 1916-1917. In civilian life he owned a pharmacy in Amarillo, Texas and helped recruit his company of young Texans, many of whom were now there with him in France.

The attack begins

Assisting the attack were French tanks, from the 2nd and 3rd Battalion, 501e Régiment de chars de combat (501e RCC). Six Renault FT tanks would support the 142nd Infantry in its attack.

Behind the Texans and Oklahomans was a substantial host of artillery: the US 2nd Field Artillery Brigade along with the French 29e Régiment d’Artillerie and two other bataillons of heavy artillery.

As Captain Barton was giving his orders French and American artillery struck, signaling the attack. For some American officers on the front line, this was their first notice that an attack had been ordered. Explosions rocked the earth in front of them and smoke filled the air. At about the same time, German artillery retaliated in what was described as a “literally appalling” counter-barrage.

From the time the 142nd Infantry and other parts of the 71st Brigade took their positions twenty-four hours before, the Germans had anticipated the attack. And while the Allies were sending their shells over and beyond the German front line, the German shots were right on target. Explosions from German artillery hit along the front line. More German shells hit the rest of the Brigade, who were located farther back. Machine gun bullets filled the air.

Over the top

After watching American and French shells hit as far as three hundred yards off-target, men of the 142nd got ready to step into the fight. Captain Barton signaled the Regiment’s mortar platoon and one-pounder guns. Figuring “we will never need them worse”, he had them fire directly into the woods in front of them. All of the Regiment’s grenades were left behind on October 4 when they were deployed.

Twenty to thirty minutes after Allied artillery opened fire, the barrage shifted further away. Captain Barton’s Company G and the one next to it, Company H, were the first to attack. Texas and Oklahoma Guardsmen rushed forward in short sprints, hitting the dirt after several yards. As they were advancing, Companies E and F followed suit.

As the forward groups of men reached the strands of barbed wire, the woods in front of them lit up with flashes from machine gun barrels. The German front line was better defended than at first believed. Machine gun bullets and explosions filled the air and took their toll. Soldiers felt that every cubic foot of air had metal hurtling through it.

The attack on Barton’s Hill

In the woods directly in front of him, Captain Barton saw muzzle flashes from four German dugouts. After capturing one of them, Platoon commander Gordon Porter of Wichita Falls crawled from hole to hole toward another. Men taking shelter with 1st Lt. Porter were shot dead by the machine gunners, who shifted their attention when another wave of the 142nd (Companies I, K, L and M) appeared in view. Porter made his move on the enemy. Later he said, “evidently he didn’t see me so I walked right on the two of them” and captured them. Porter then turned the gun around and fired on Germans rushing forward to hold their line.

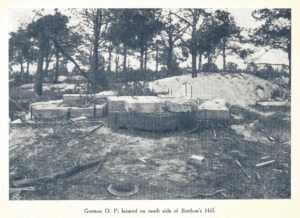

As Barton and his men maneuvered around one dugout and captured it, another hidden dugout would open fire. This process continued until the woods was cleared of Germans. Company G captured between fifty and sixty Germans and five machine guns there. When they emerged from the woods, they saw low, flat fields with concrete machine gun nests.

As the men advanced beyond the treeline, they came under heavy machine gun fire from their front and right. They were ahead of other American troops now. Captain Barton and his men advanced through the gunfire and explosives to neutralize the strong points. As he moved from one shell crater to another, Barton encountered men from other companies. The assault force had become intermixed and disorganized. Because of the trees, Barton could not see the rest of his unit, but the enemy could see him. Barton and his men captured about 150 more Germans and many machine guns. But of the four company commanders that went forward in the first wave of the assault, Barton was the last man standing. The others had all been wounded or killed.

Toward the village

Captain Barton was now the battlefield leader of what was left of Companies E, F, G and H: the Second Battalion. He was on the Saint-Étienne – Orfeuil road leading his troops to Saint-Étienne. German artillery was falling also with green and yellow bursts of poison gas. Barton and his men advanced several hundred yards toward the village and his advance soldiers found men from Company L of Third Battalion. Eventually Barton found their commander, Captain Steve Lillard of Decatur, who was also leading men from Company I.

As Barton and Lillard were assessing the situation, the Germans counterattacked on the American right. The 142nd had advanced further than the next unit on their right, the 141st Infantry, and were exposed to the enemy. Attempts to bring up reinforcements were unsuccessful, and five messengers Barton sent back to his commander were all wounded or killed. Captains Barton and Lillard decided to withdraw their men from the open field back to the wooded hill where there was, as Barton put it, “an abundance of German machine guns and plenty of German ammunition.”

As they retreated the Captains found the Third Battalion commander and some men from Company K. They all made their way back to the wooded hilltop and dug in. Barton found a company of U.S. Marines from the Second Division and the 142nd Infantry’s Machine Gun Company and convinced them to dig in as well, commenting later, “This made the world look brighter.”

For his actions in the assault on October 8-10, 1918, and notably for his leadership in the capture and defense of “Barton’s Hill”, Captain Thomas D. Barton of Amarillo was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for extraordinary heroism in the face of the enemy.

Resources

Texas Military Forces Museum: The 71st Brigade at St. Etienne