As winter wore on in northeast France in 1919, men of the 36th Infantry Division prepared themselves for a long stay. As soon as the Armistice was signed, rumors traveled among the 2,057,675 uniformed Americans in Europe about when they were going home. Rumor was about all the average American had to go on because there was no pattern when it came to the units first sent home.

The men of the 36th Division were told by their commander that they would be among the last divisions sent home, though that did not turn out to be true. Soldiers then expected that they would board ship for the States sometime in July 1919. American troops occupying western Germany would have to stay even longer.

Even though the 36th Division felt resigned to a long residence in France, movement was happening across the American Expeditionary Forces in 1919. This was evident when 115 men returned to the 36th that winter from the 81st Division. They and nearly 2,000 other Arrowheads had been assigned to other divisions such as the 42nd, 90th and 81st in September 1918 during the St. Mihiel and Argonne Offensives.

Tale of the 61st

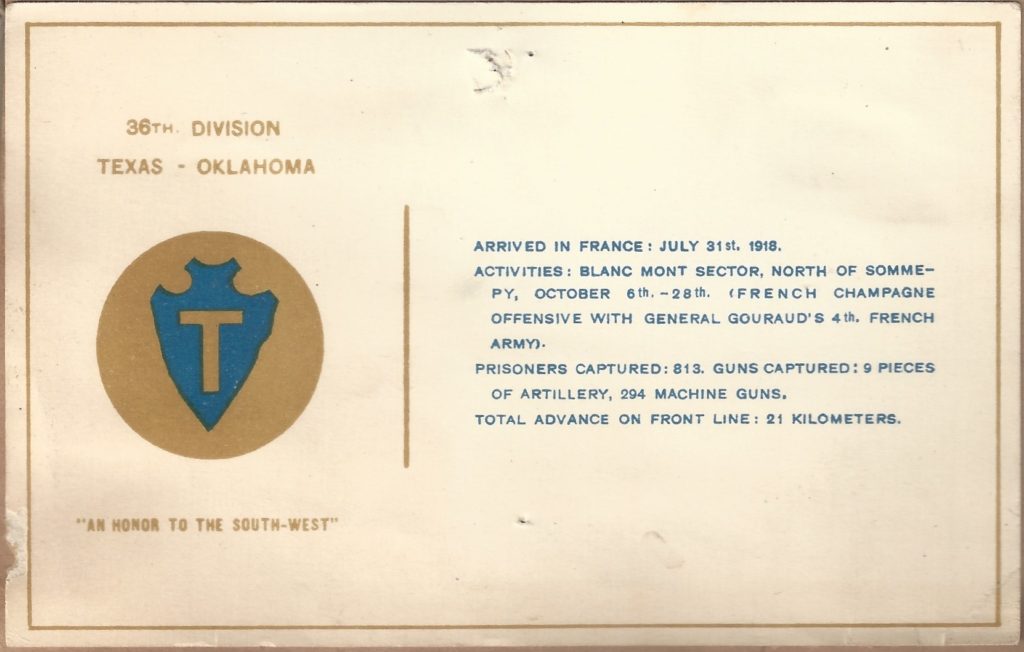

In February 1919, the 61st Artillery Brigade got its orders to pack for home. The 61st was part of the 36th Infantry Division but was separated from it in August 1918 when the division arrived in France. The 61st Artillery Brigade was formed at Camp Bowie in September 1917 from Texas and Oklahoma National Guard units. This included the 1st Texas Cavalry Regiment, whose B Troop was headquartered in Amarillo.

The first units of the 61st arrived in Brest on August 11, 1918 with the 36th Division. After five days there, they boarded trains for Redon in Brittany. Companies C and D of the 111th Ammunition Train did not go with the 61st Brigade but stayed with the 36th Division the whole time they were in France. After two weeks camped in the vicinity of Redon, the 61st Brigade marched to artillery school at Coëtquidan.

Training begins

The base at Coëtquidan was large enough, at forty square miles, to house and train two brigades at a time. At least ten U.S. Army brigades trained there from the summer of 1917. The reason for the extended training was twofold: First, American artillery units such as those in the 61st had very basic training in the States. Second, very few American cannon were used by the Army in Europe in World War I.

In the interest of transporting as many American troops to Europe as possible, little room on ships was available for American heavy weapons. Most artillery pieces, mortars, and tanks the United States produced remained stateside. Americans fought in French tanks and airplanes, for the most part, and shot French cannon. The French provided excellent pieces, including the Modèle 1897 75mm field gun and the 155mm Schneider howitzer.

With a staff of French instructors, training began at Coëtquidan in September. The American gunners found they had to learn everything from scratch. Compass work, signaling, and learning every part of the new guns was in the curriculum. Their first practice shots on the firing range in late September were disappointing. After four weeks of intensive training, however, even veteran French instructors were satisfied.

61st stands down

The 61st Artillery Brigade was trained and ready for action by the last week of October 1918. They were on schedule to rejoin the 36th Infantry Division in its second deployment to the battlefield when, on November 11th, Germany capitulated. The 61st remained at Coëtquidan uncertain about their future.

On February 18, 1919, the 61st was ordered to break camp. Being stationed in Brittany near the ocean, it made sense to the AEF to send them home earlier than most. The brigade began to leave Coëtquidan on February 21st and three days later all had left camp. The 61st then underwent a series of inspections and medical examinations at the port of embarkation in Saint Nazaire. This period of time was remembered by Americans overseas as the least enjoyable part, besides combat, of their time in France.

The 61st Artillery Brigade boarded a flotilla of ships leaving Saint Nazaire beginning on February 25th. By March 11th, they had all left France. After a stormy transatlantic journey, the Brigade was in Newport News, Virginia and eventually back in Texas. The 61st Artillery Brigade was inactivated on April 10th, 1919.

The Arrow Head

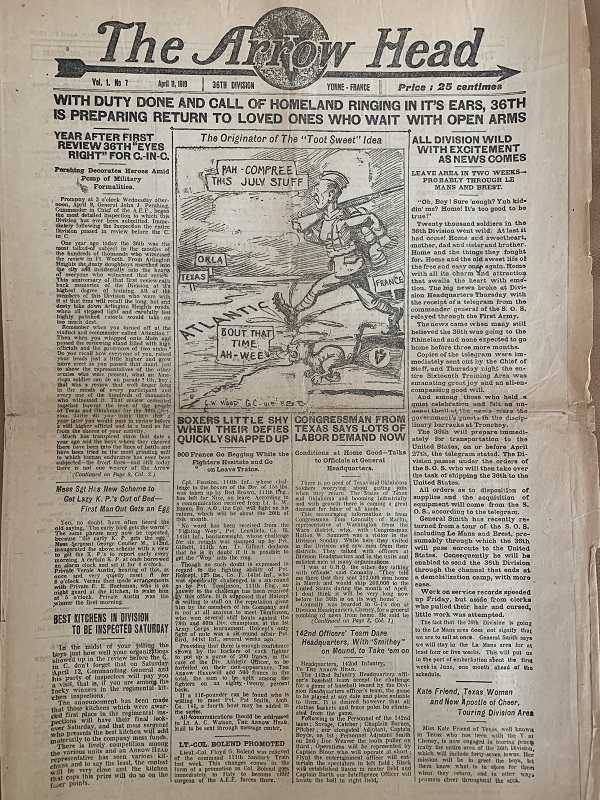

February 27, 1919 saw the first appearance of the 36th Division’s newspaper, The Arrow Head. Publishing a newspaper did a great deal to bolster the morale of the division during its time in the Sixteenth Training Area. It was written, edited, and published by enlisted men. Its editor-in-chief was a private who previously worked at the Dallas Evening Journal. The Arrow Head was an immediate success among the men, growing to a weekly circulation of ten thousand copies. Ten issues were published between February 27 and May 2, 1919.

The paper took as its model the weekly journal of the AEF, Stars and Stripes. “By and for the soldiers of the A.E.F.”, Stars and Stripes was published in France for seventy-one weeks between February 1918 and June 1919. It was also written and edited by enlisted men and came to represent the voice of the American soldier serving overseas. Read more about the Stars and Stripes here.

As any local paper, The Arrow Head published the news and sports reports everyone in the division wanted to see. Each of the constituent organizations had a column in the paper to report its weekly news. The Arrow Head also published letters from soldiers and creative work including poems and cartoons that caustically lampooned army life.