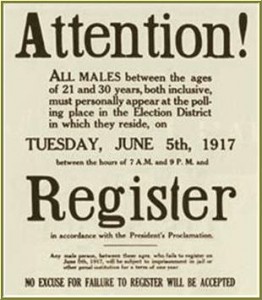

June 5th, 1917 was draft registration day across the United States. Men between the ages of 21 and 30 filled out registration cards in one of 4,648 locations nationwide. Nearly ten million men filled out draft cards on June 5th. Over 400,000 Texans registered on the first day. The event was marked with celebrations across the state. It was a citywide holiday in Amarillo, where Civil War veterans lead a parade. They were followed by new army recruits and men who had registered for the draft. Because this was still the segregated South, African-Americans who participated marched in the back of the parade.

The experience was similar across Northwest Texas and the Panhandle. In Denton, those who registered received a red, white and blue over army khaki ribbon to wear. Wichita Falls also declared a holiday on June 5th which included a patriotic rally and many speeches. The response to registration day in the region exceeded expectations and, in some cases, the supply of draft cards to be filled out.

Resistance to the Draft

There was still dissension over the draft in the region and for the most part it was sporadic and disorganized. For example, recruitment posters were torn down or defaced in Fort Worth. In addition, anti-draft leaflets were brought into Dallas from out of state. A few individuals still spoke out against the draft and President Wilson.

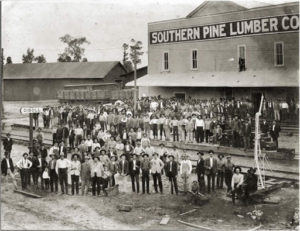

Dissension over the draft took a bizarrely dark turn in mid-May. In Snyder, located about halfway between Abilene and Lubbock, seven men were arrested for conspiring to forcibly resist the draft. News came from Dallas, where the men were held, that they were all members of the Farmers’ and Laborers’ Protective Association, the FLPA. The FLPA was founded in 1915 partly as a consumer cooperative for rural workers. By that time the majority of farm workers in the region were tenant farmers (who rented land), not landowners. The FLPA operated a feed and supply co-op run by its membership and was considered noncontroversial at the time. In fact, the FLPA was becoming less active by late 1916.

Political action in rural America

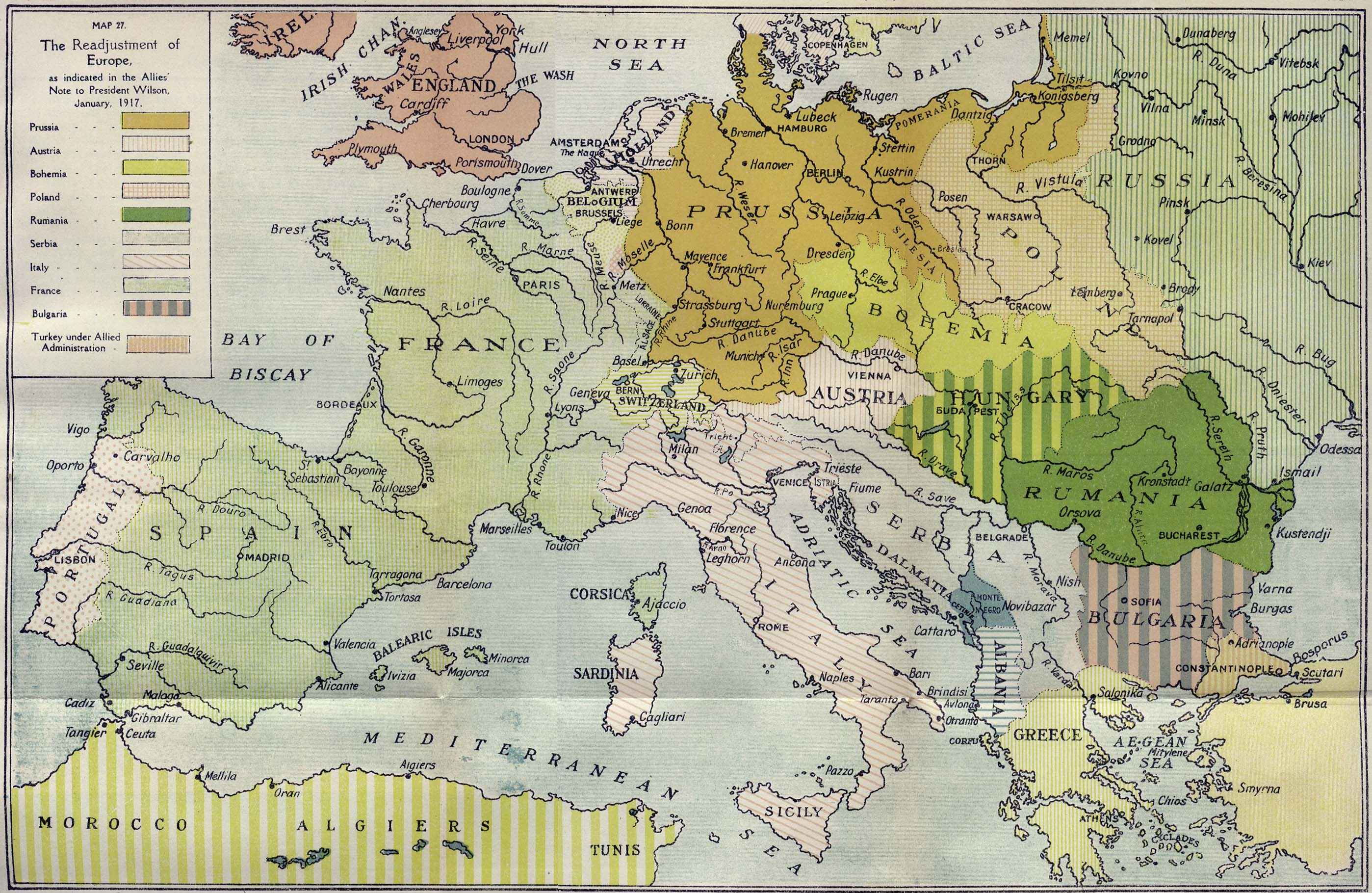

One can trace organized labor in the rural South and West back to the 1870’s through organizations such as the Knights of Labor and the Farmers’ Alliance. They were part of the progressive movement, a broad effort to bring social, political and labor reforms in the wake of America’s rapid industrialization. The movement was well represented in the Republican and Democratic parties. For instance, Republican president Teddy Roosevelt and Democrat Woodrow Wilson were also progressives.

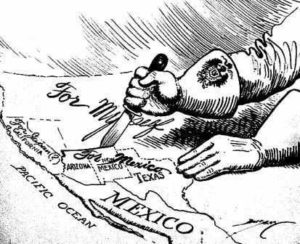

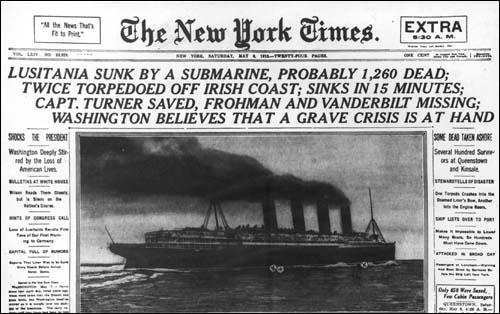

Socialism was also on the progressive spectrum and tenant farmers, miners and other rural laborers saw its appeal. As the U.S. economy weakened in the years before the European war, many workers across the country had become radicalized. Leading members of labor groups tended to be active in the Socialist Party or the International Workers of the World (I.W.W., or “the Wobblies”, if you remember them). Unsurprisingly, this was the case with the FLPA.

Interest in the FLPA increased in late 1916 as war with Germany seemed likely. By spring 1917 it had ten thousand members organized into 205 local organizations in Texas. Among their members were I.W.W. activist G. T. Bryant and Texas Socialist W. P. Webb. One hundred and eighty-five delegates met in Cisco, between Fort Worth and Abilene, at the FLPA convention on May 5th. Congress had declared war barely one month before, and emotions were running hot. However multiple resolutions to resist the draft, by force if necessary, were defeated at the May 5th convention.

Word gets out

Word about the intemperate remarks at Cisco reached the authorities. Consequently a grand jury was convened in San Angelo on May 17th. It resulted in the arrests of six farm laborers and one railroad foreman in nearby Coke County on May 25th. Soon more grand juries convened in Abilene, Dallas and Tyler. As a result, seventy-three were arrested in Texas for conspiracy to commit treason. Fifty-three were members of the FLPA.

News of the arrests, and of a socialist plot to violently resist the draft, made headlines across the country. In September 1917 fifty of the indicted were tried in Federal court in Abilene. Even so, all were acquitted except three office holders in the FLPA, who spent up to six years in Federal prison. (Read more about the FLPA here)