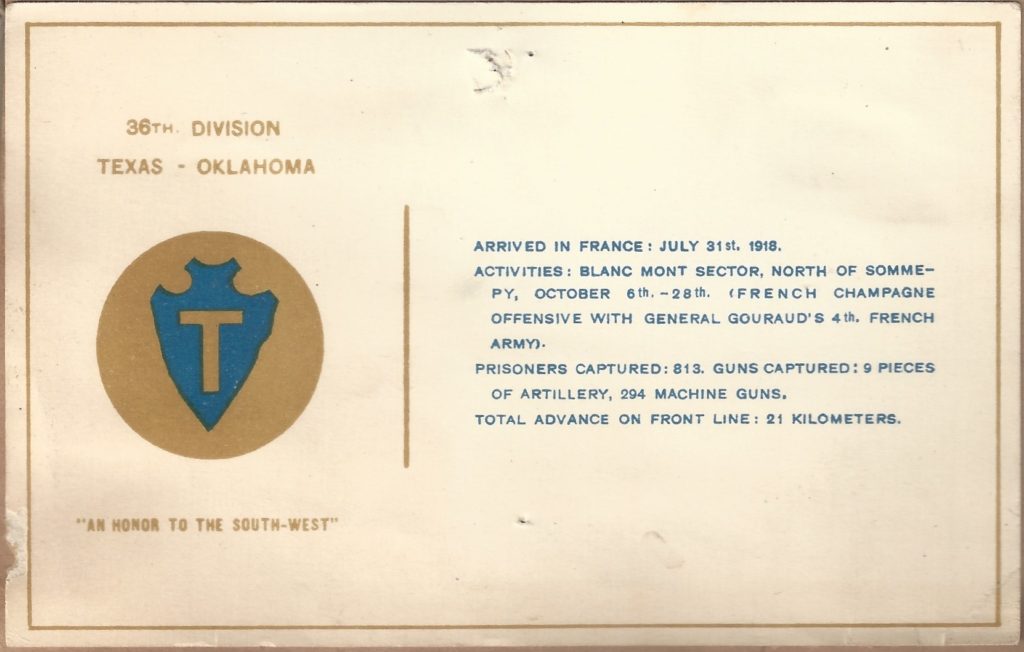

News of the 36th Division’s embarkment order raced through the Sixteenth Training Area in early April 1919. Soldiers of the 36th did not expect to be sent home until July or August. That they were going home this early was completely unexpected. There had even been rumors in the division that they would have to serve a tour of duty in Germany in the Army of Occupation.

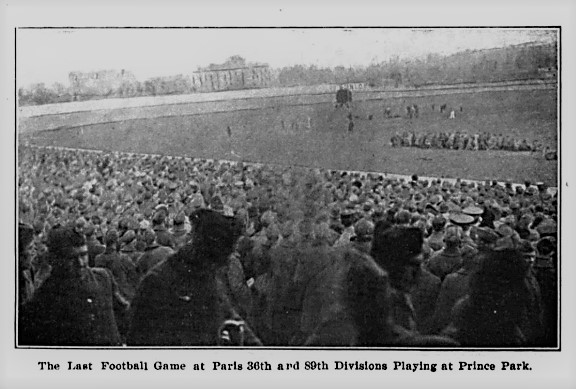

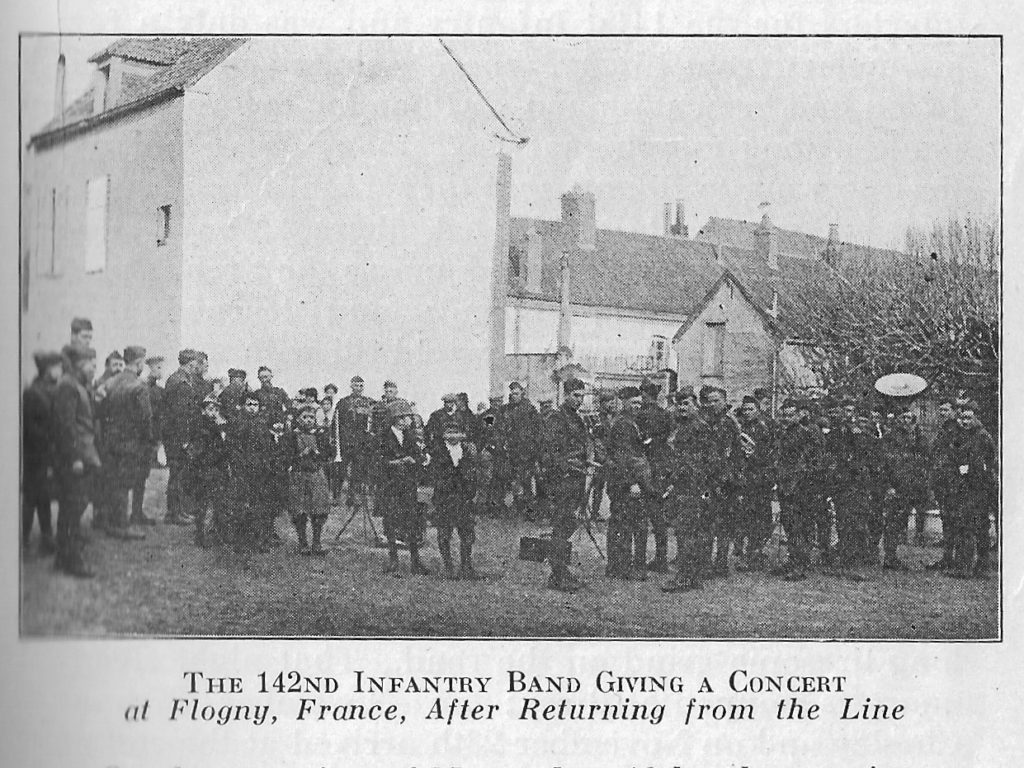

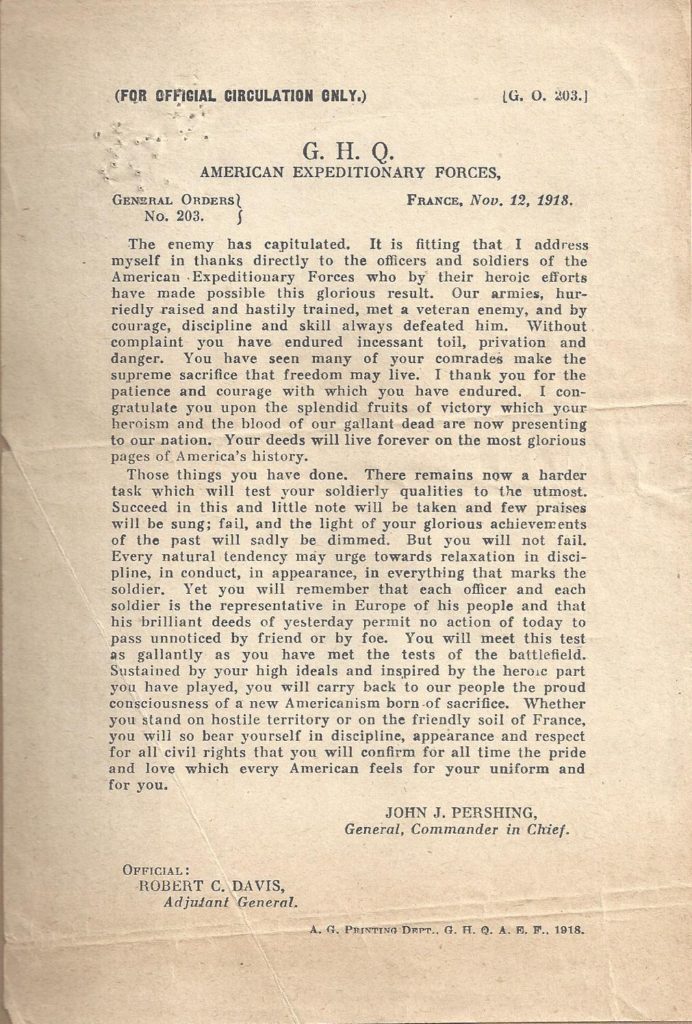

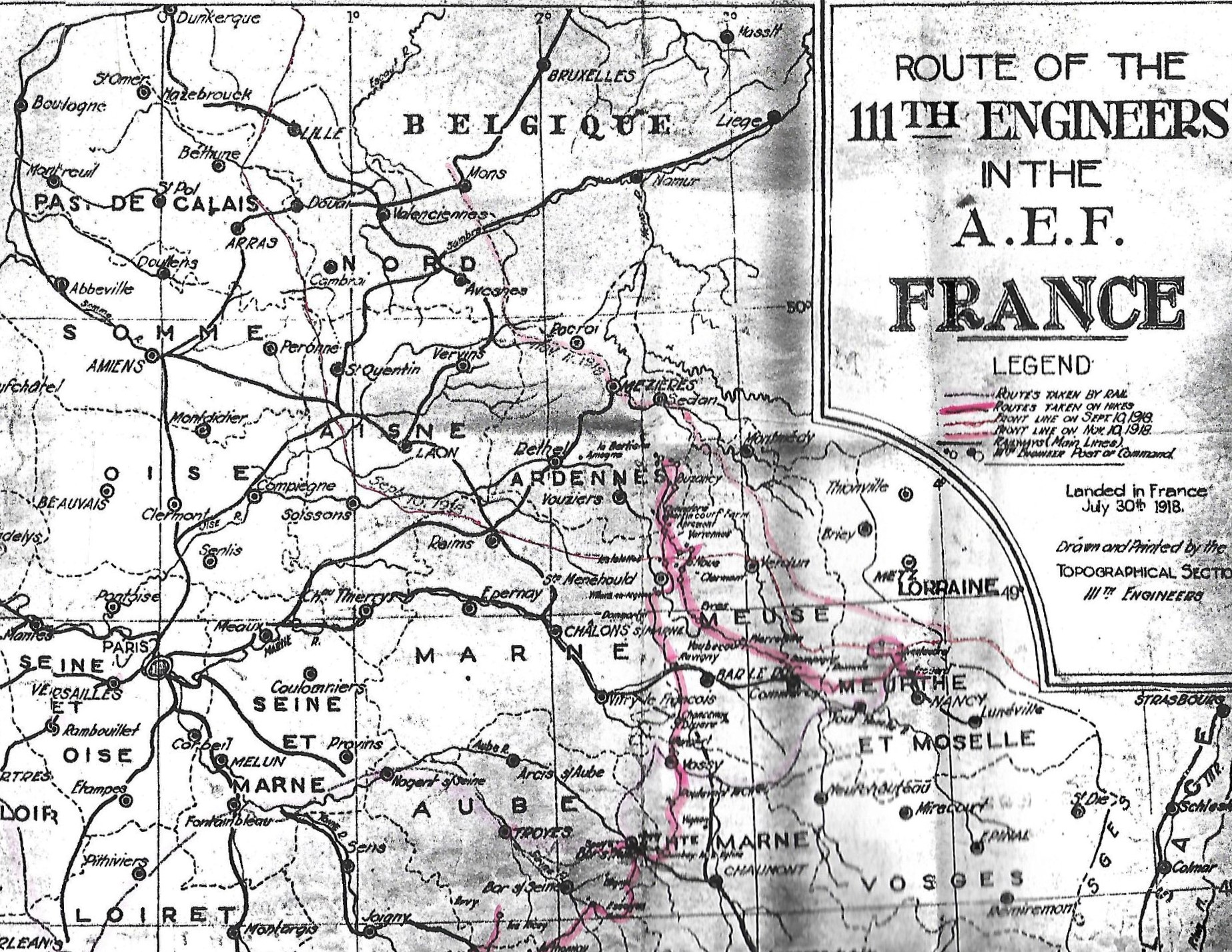

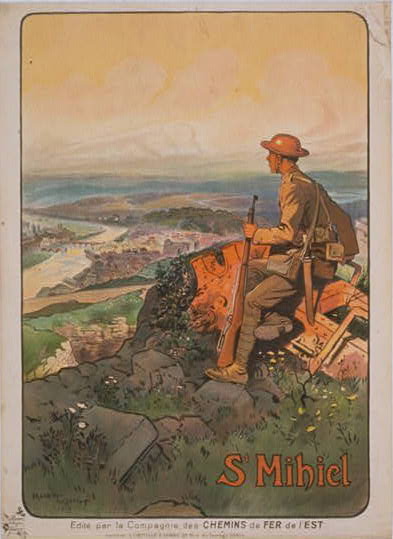

All worries of months of extra duty, now that the fighting was over, were swept away by the thought of finally going home. The 36th Infantry Division arrived in France at the end of July 1918. Three and a half months later, the fighting stopped. The division had just entered combat, with twenty-three days in harm’s way when the Armistice was signed on November 11th. Since that time the nearly twenty thousand men of the 36th were stationed in northeast France, waiting. Now the wait was near an end.

Packing for home

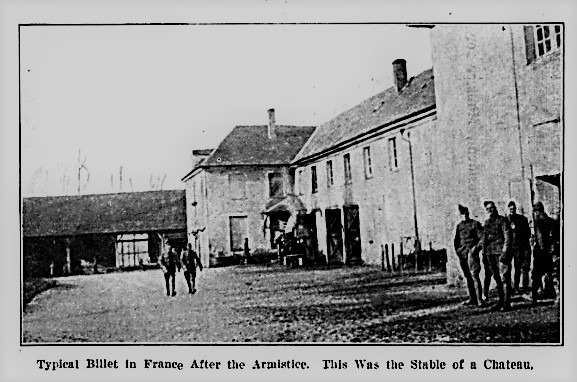

The remaining weeks at the Sixteenth Training Area were a blur of activity. Equipment had to be returned to the Army. Bills had to be paid at local businesses. Soldiers were already sending home exotic items such as German helmets, knives, and medals (firearms and ammunition were harder to smuggle). Most of all, there were inspections: Uniforms, personal gear, and the men themselves were inspected thoroughly as the 36th prepared to depart.

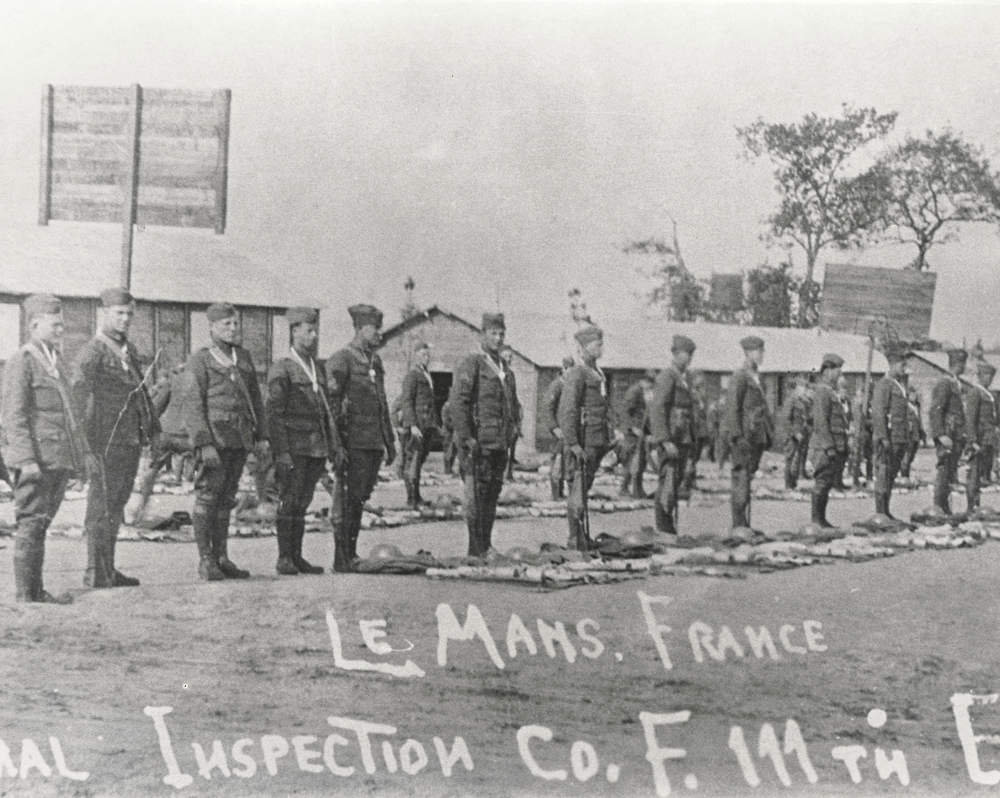

The first team from division headquarters left Tonnerre on April 26th for Le Mans, site of the American Embarkation Center. Returning troops stayed in or near Le Mans to undergo inspections and wait for their ship. From Le Mans troops would travel by train to one of three French ports for transport home.

Get the boys home!

That the 36th Infantry Division was going home in May and not months later was the result of an incredible effort of the US Government. America wanted its soldiers home, and elected officials heard about little else from their constituents since the Armistice was signed. The result was a speedier process of transporting the massive American force in Europe. More ships joined the transport fleet. More docking space was added to French ports. In addition, larger American trains were sent over to help the French rail system.

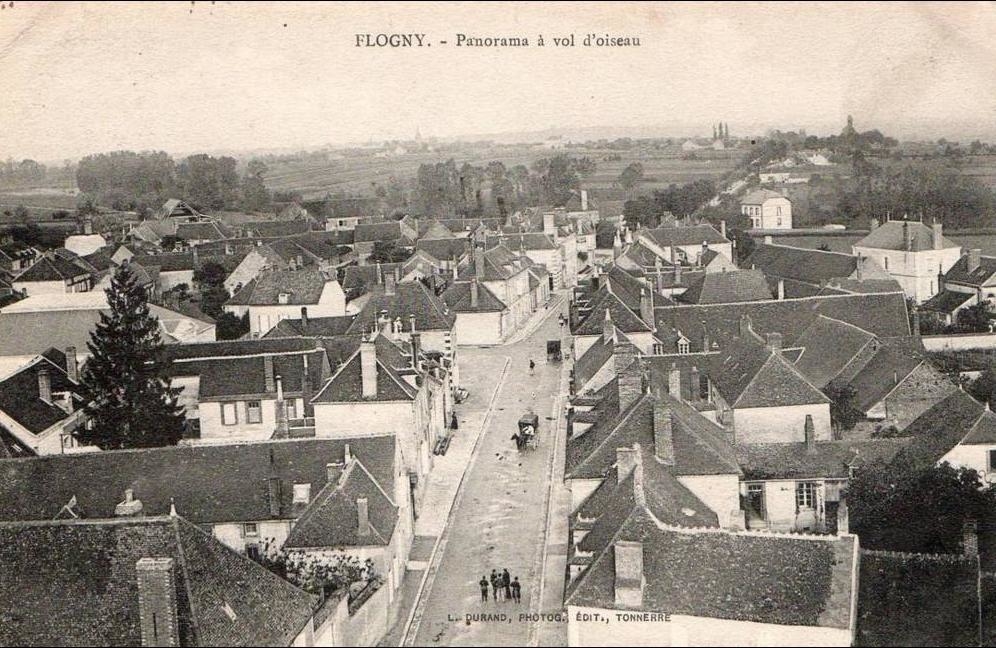

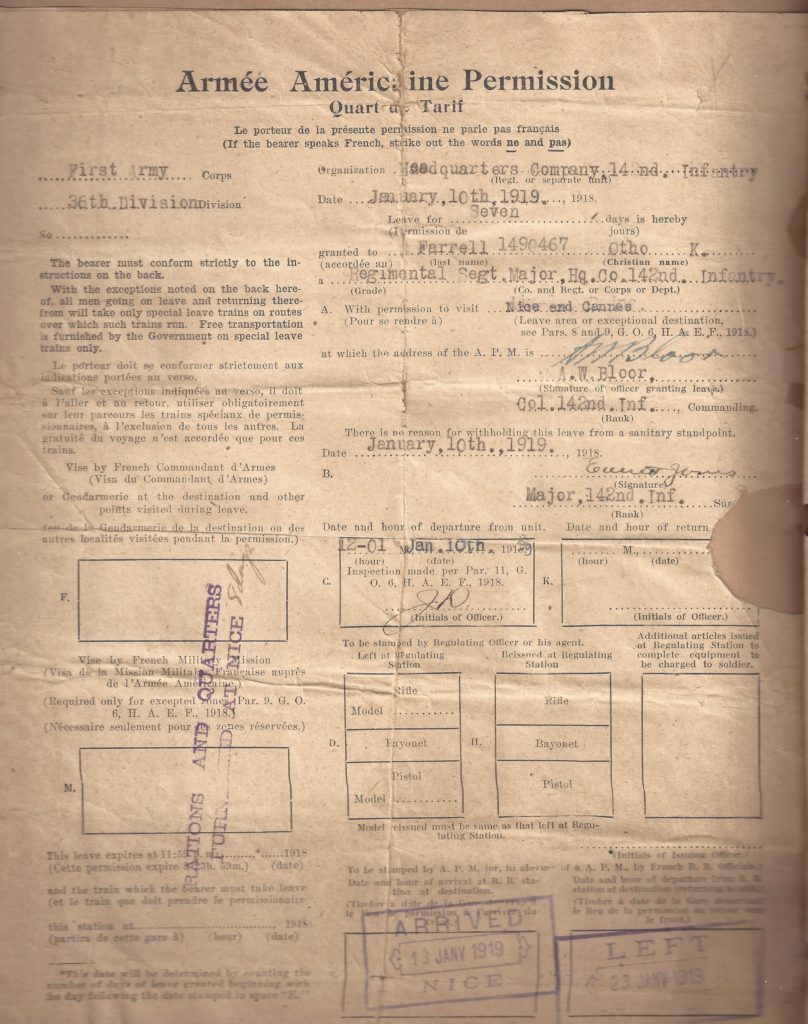

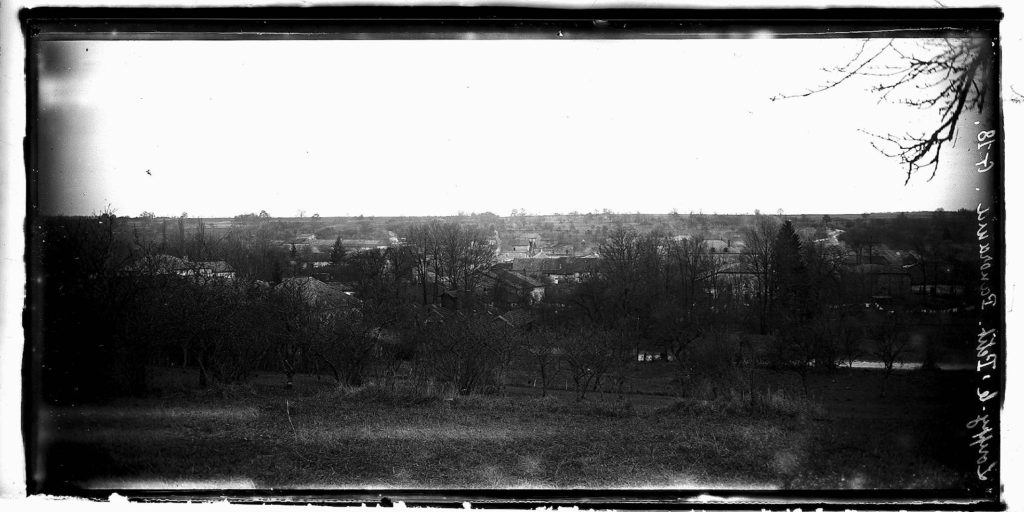

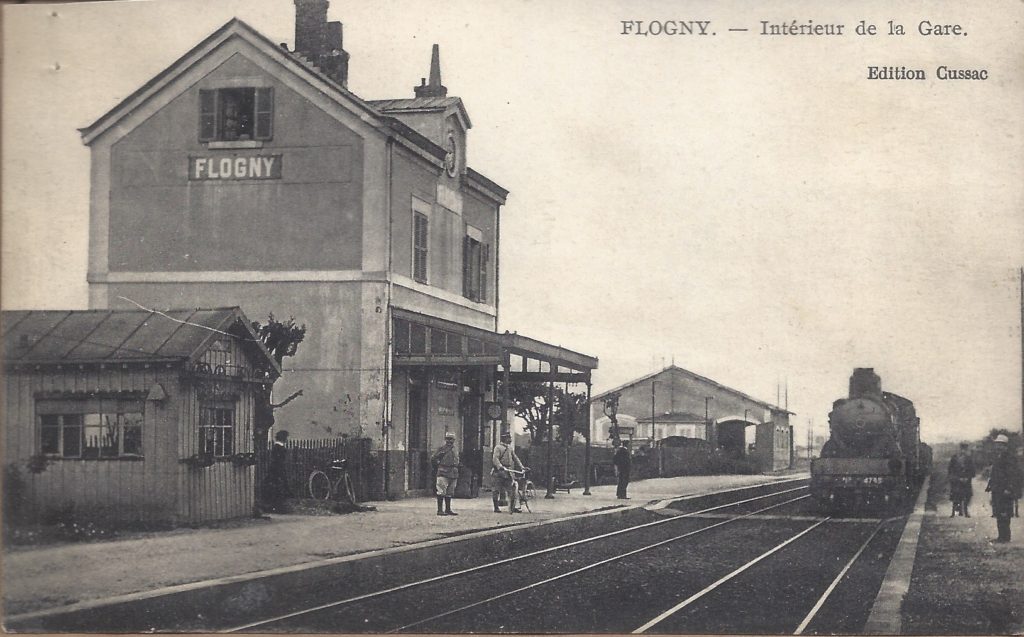

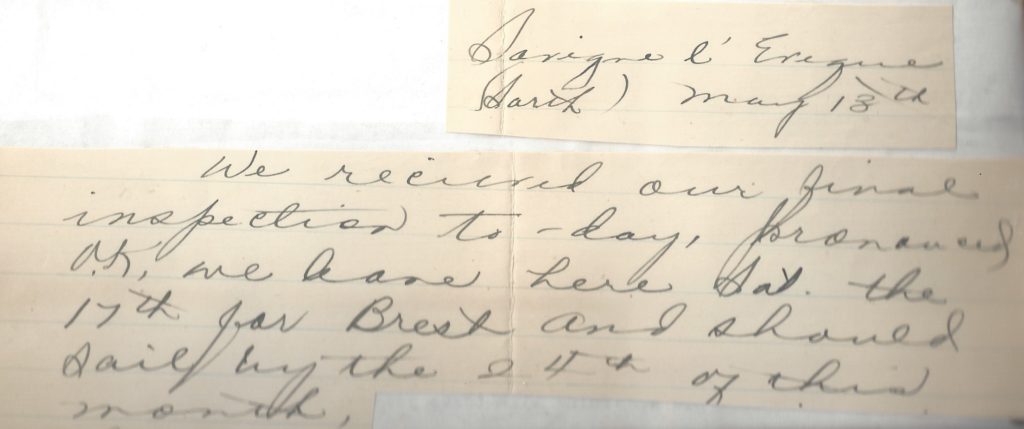

The 36th Division, when it departed the Sixteenth Training Area, entrained at Tonnerre, Flogny, Tanlay, Ervy and Jeungny. It took sixteen trainloads to move the division. On May 2, 1919, the first troops left the Sixteenth Training Area in the familiar 40-and-8 (40 Hommes et 8 Chevaux) boxcars. This time, Regimental Sergeant Major O.K. Farrell was not among them; NCOs rode in coaches. The thirty-hour trip took them across central France to Le Mans. Soldiers in the 142nd Infantry Regiment detrained in Champagné, a town just east of Le Mans. From there they marched to Savigné-l’Évêque, about five miles to the north.

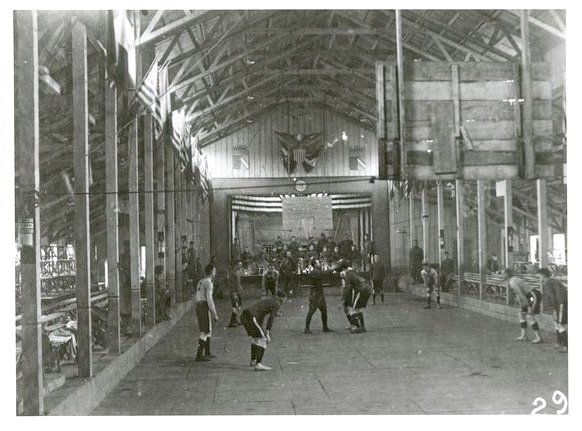

Life at the Embarkation Center

By May 5th, the 142nd Infantry Regiment reassembled in Savigné-l’Évêque. While there, they learned about the AEF war against lice. Before embarking for America, everyone and everything had to be deloused. The Army set up delousing stations all across the American Embarkation Center; and there were more at each of the ports. Every soldier had to give up all his worldly goods to be sent through a large steel tank. Inside the tank the items were subjected to steam and delousing chemicals. While this was happening, the men were led through a bathhouse where they washed. Clean soldiers emerged to receive their freshly steamed (and still damp) clothes.

Life in the Embarkation Center was among the less enjoyable tasks for Americans serving overseas. This was because it was filled with record checking and health exams, inspections, and long lines for everything. The freedom of the men to move about and explore was very limited. No one wanted to fall afoul of the AEC staff and possibly delay their passage home. Above all, going home was the mission of these men. One soldier on the 142nd wrote his family, “Believe me, it is good to think about getting back home and among friends, for the people here are strange to me, and when I get back to the states I will take myself back to Rosston faster than the Germans took themselves back to Hun-land when once they started.”