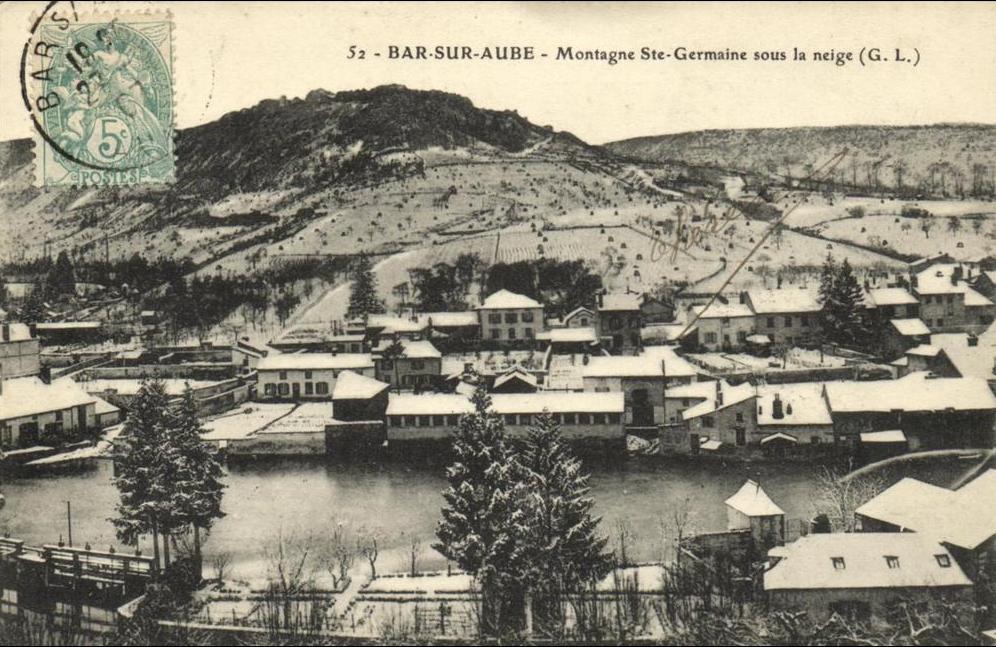

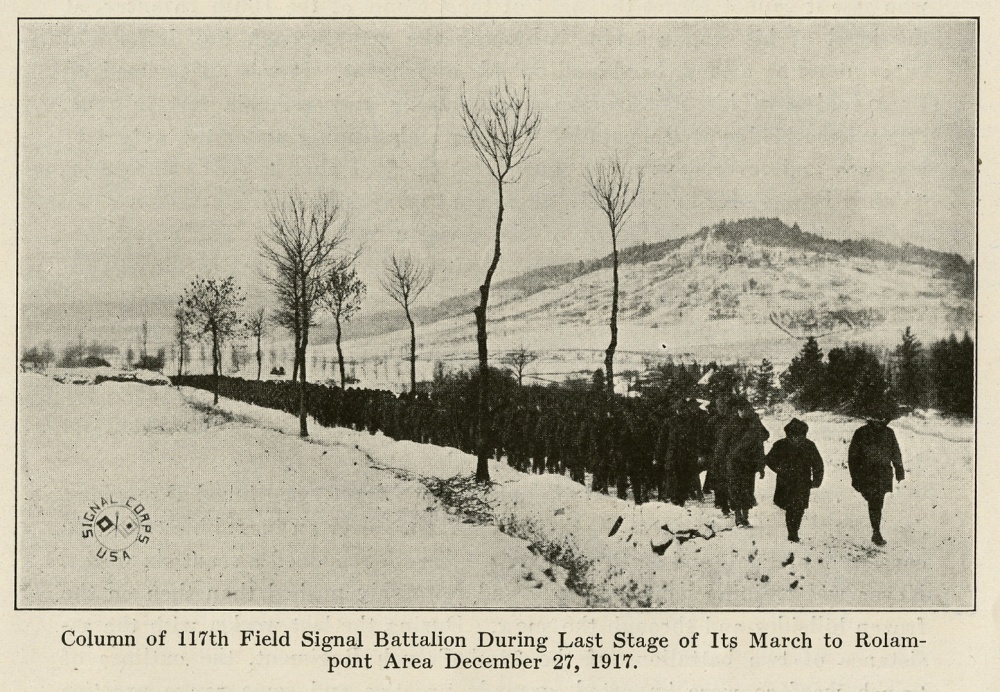

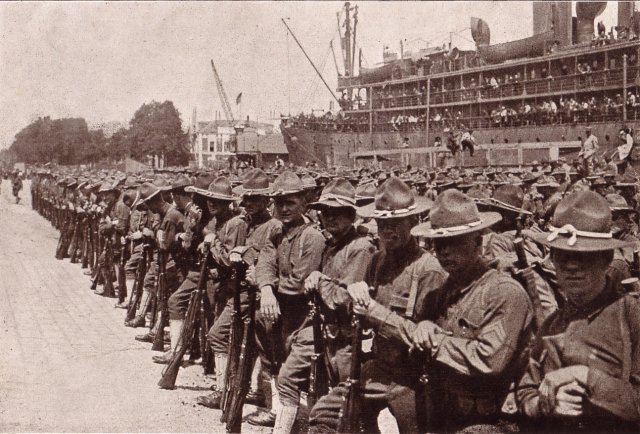

On his seventh day at Saint Nazaire, France, Otho Farrell and Headquarters Company, 142nd Infantry Regiment marched to the train station. It was the beginning of their journey inland, to final training before combat. By August 6th, the 142nd Infantry was spread over three ports of entry on the Atlantic coast of France. The regiment would be reunited at the training area, Area 13.

Soldiers of the 36th Infantry Division lined up at train stations near Bordeaux, Saint Nazaire and Brest for the trip. Non-commissioned officers (sergeants) rode in second-class coaches. The rest of the enlisted men traveled in 40-and-8s. A 40-and-8 is a French boxcar, much smaller than its American counterpart. Each one was to carry forty men, or eight horses (40 Hommes/8 Chevaux). Standing inside of one today makes one wonder how forty men with their gear could possibly stand, much less sit or eat or sleep in it. There was no toilet, you just stood on the running board outside. The officers, by the way, rode in first class coaches.

Experiencing France

Traveling through France packed with thirty-nine of your closest chums in a boxcar in August is no vacation. But the men did see a lot of France. Depending on where he started from, a soldier in the 36th traveled through Tours, Bourges, Orléans, Dijon, or else around Versailles and Paris. Crowding in the boxcars was unbearable and some rode on top of the train. The 142nd experienced another fatality in France when a private from Company G was knocked off his boxcar by a low bridge.

Along the way, the men of the 36th saw ancient cities and towns, cathedrals, factories and farms. Farmers and ranchers from the American west marveled at the small stonewalled fields and horse-drawn farming equipment. They traveled through vineyards and mountain passes, villages and fields of grain in summer. If the rude condition of their transit could be forgotten, France was starting to look better.

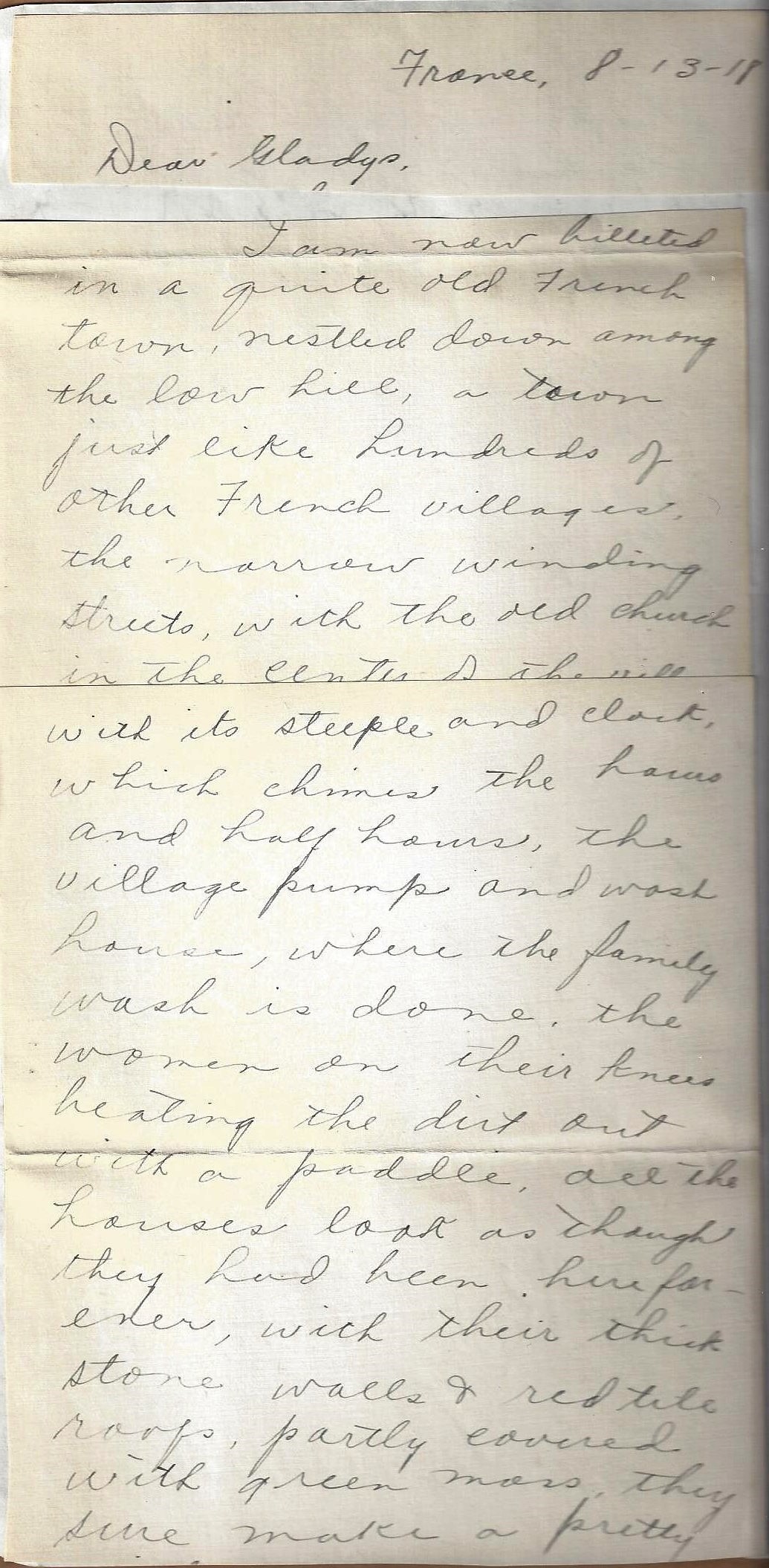

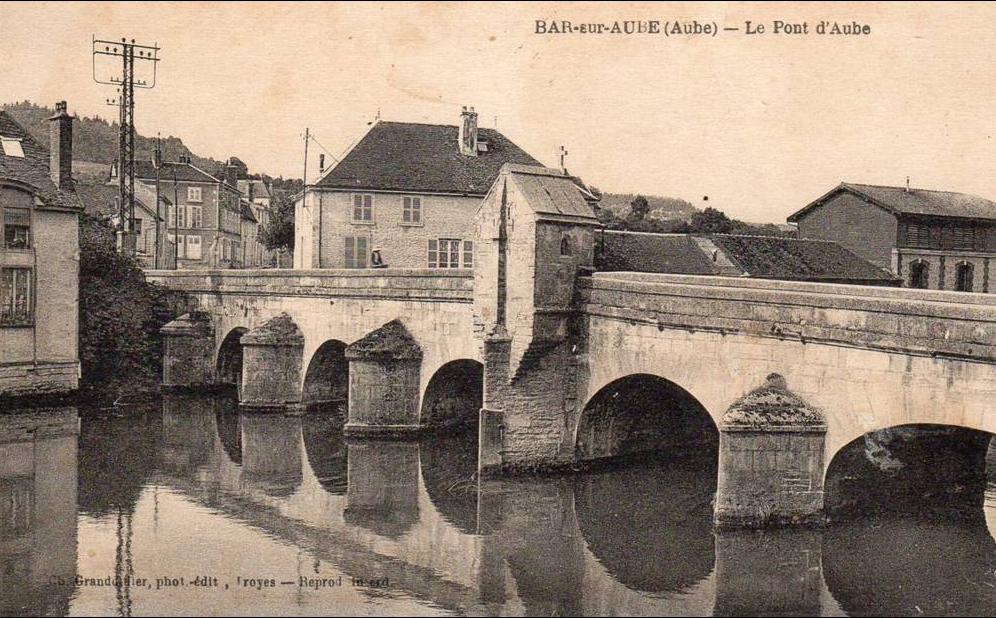

Bar-sur-Aube

Training Area 13 was located in the Aube département of France, 120 miles southeast of Paris. The train stopped in Bar-sur-Aube, where the Division Headquarters was located. The rest of the division was spread out in towns and villages in the area. There was no army camp or fort; the soldiers would live side by side with the local civilians. However, nearly one third of the 36th Division did not go to Area 13. Instead the 61st Field Artillery Brigade traveled to artillery camps for training.

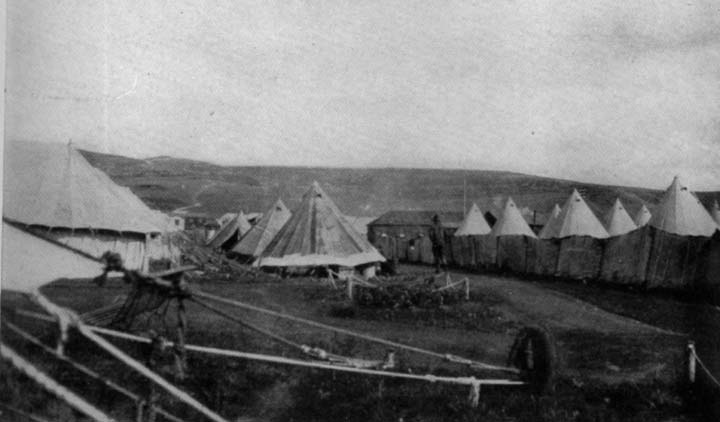

Once detrained at Bar-sur-Aube, soldiers marched to the town or village where they were to find quarters. Quarters could be in a farmhouse, a barn, a mill or outside in a tent. Accommodations were ad hoc, but most soldiers found the countryside and the relative quiet enjoyable.

Otho Farrell arrived in Bar-sur-Aube at 5 a.m. on August 8, 1918, after riding in a boxcar for thirty-six hours. He and the men of Headquarters Company marched the nine miles to the village of Bligny, arriving there by 12:45 p.m. The Headquarters staff of the 142nd Infantry found comfortable quarters in the local Château. Headquarters Company, the regiment’s medical detachment, Company C and Company D were all quartered around Bligny, as was the 71st Brigade Headquarters.

Other units of the 142nd were located nearby: 1st Battalion Headquarters and Companies A and B at Urville. 2nd Battalion Headquarters, Companies E, F and the Supply Company were billeted at Couvignon. Companies G and H were located at Bergères. 3rd Battalion Headquarters and Company L were at Montmartin. Company I was billeted at Le Puits. K Company was at Nuismont. Company M was located at Meurville, and the Machine Gun Company at Le Val Perdu.

Training the AEF way

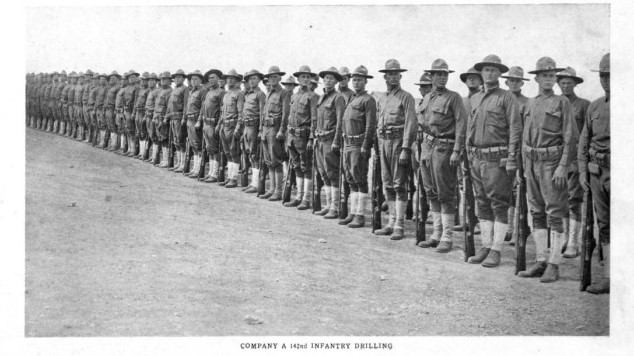

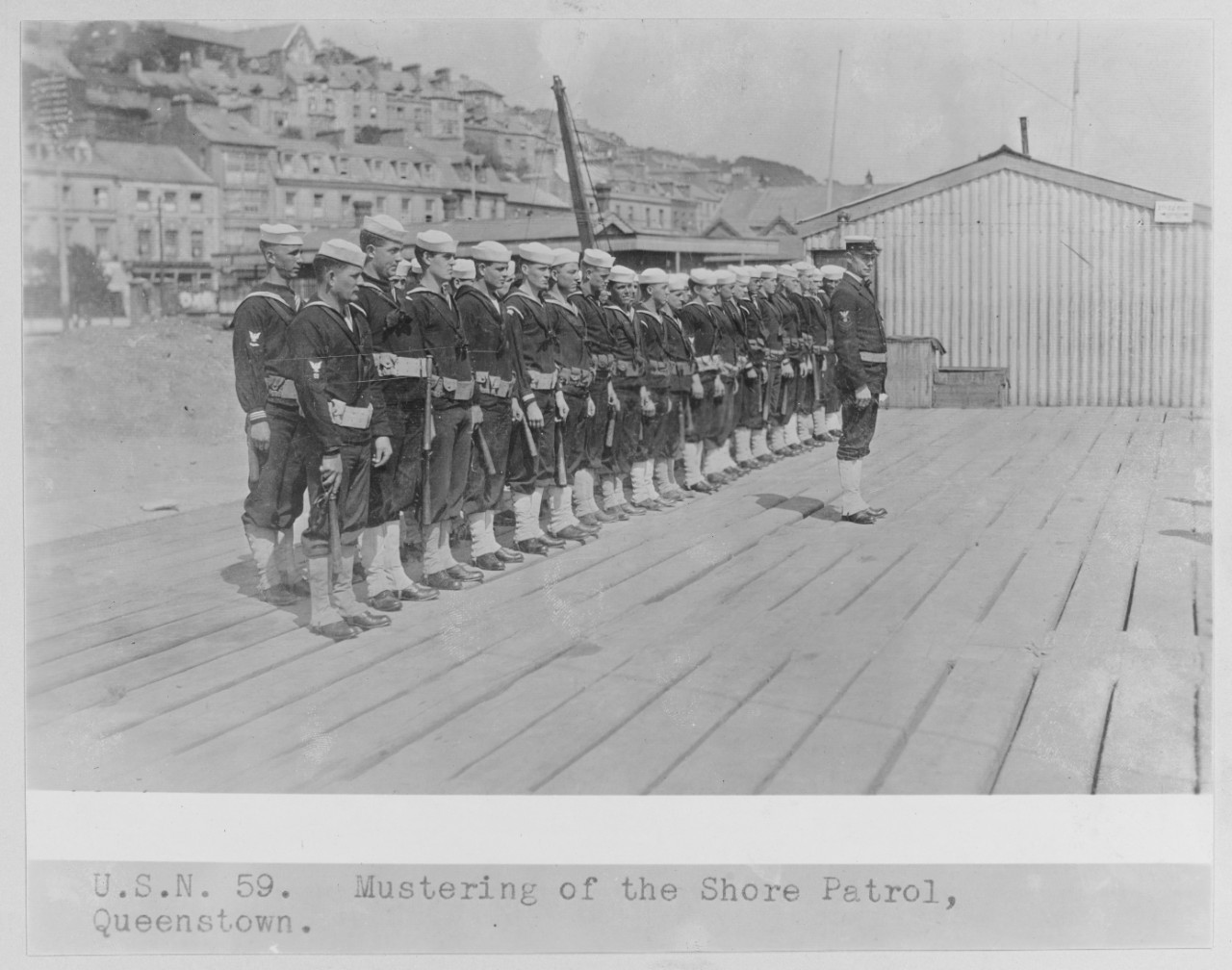

By this time in 1918, General John J. Pershing had 1,210,703 Americans serving in Europe. Fourteen months earlier he had just two battalions, 1,308 men. Even more soldiers and marines were on the way, over 300,000 new American arrivals in France during July, 1918. While the men were trained to varying levels of competence stateside, they were about to enter a machine-age war in Europe. American troops had been trained for trench warfare at home. However, Pershing and his staff saw the results of four years of deadlock in European trenches and wanted nothing to do with it.

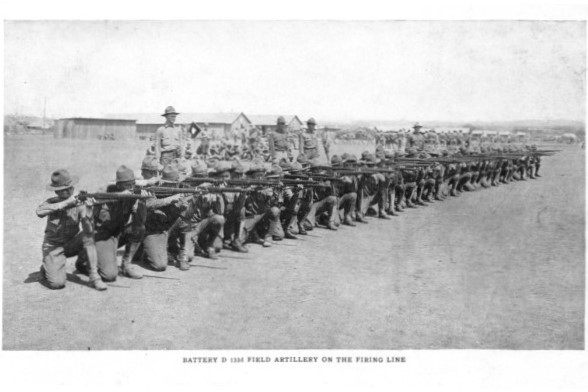

Instead the American Expeditionary Forces taught open warfare doctrine; an aggressive, mobile tactic designed to move the Germans from their trenches in order to beat them. As a commander, Pershing planned to rely on his strength of American marksmanship and physical stamina to win battles and the war. Part of this tactic must have come from the wish to avoid the grinding, unrewarding war of attrition that turned the fields of France and Belgium into a slaughterhouse. But part of Pershing’s plan was practical as the front line, for the first time in nearly four years, was beginning to crack.

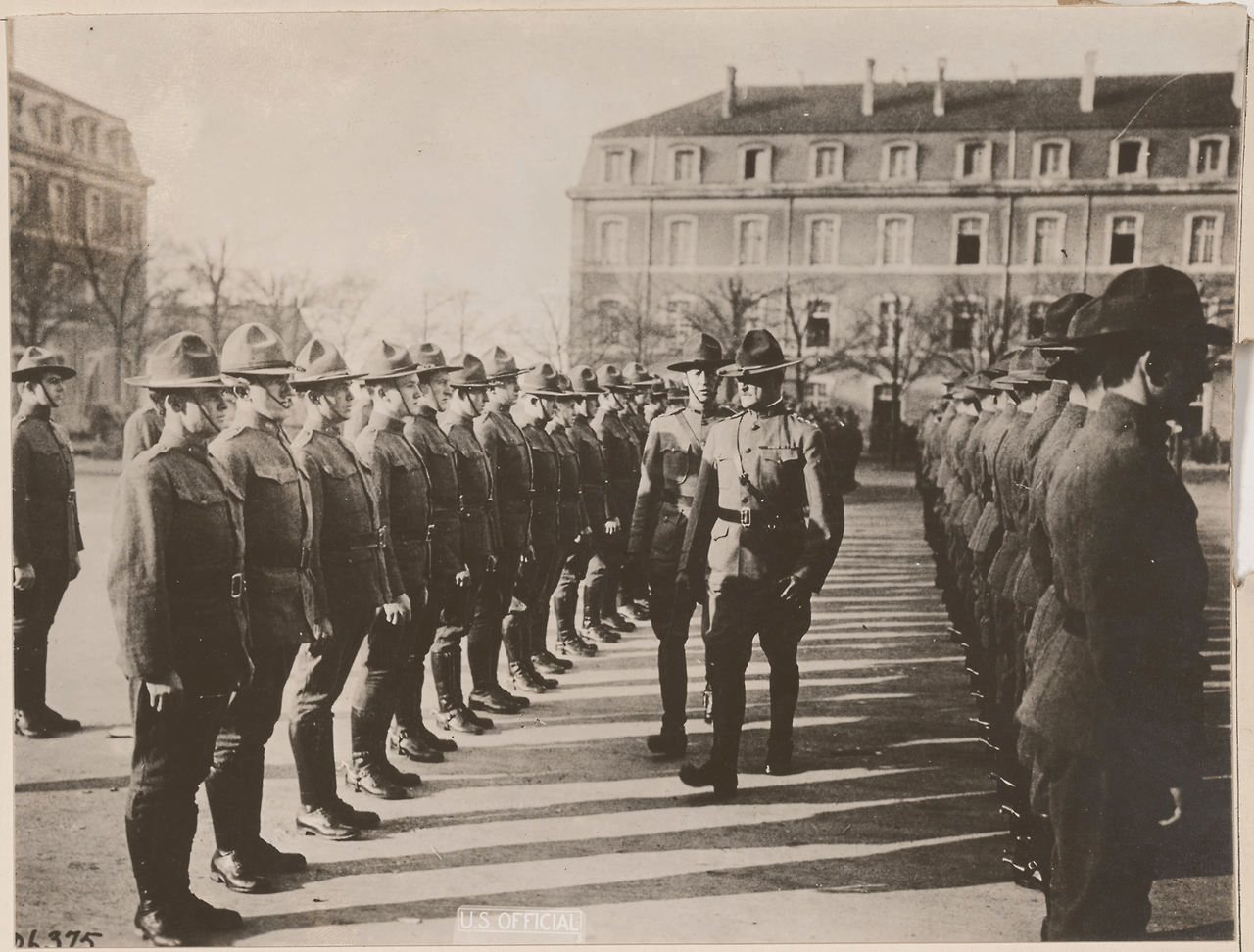

Training Area 13

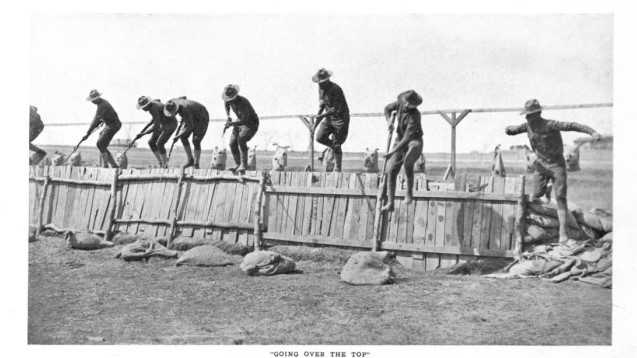

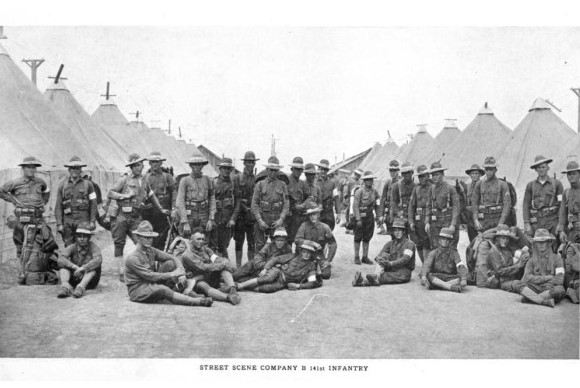

Pershing wanted his men to take German fortified points in combined-arms thrusts with stopwatch precision. To get to that level, the men had to learn anew how to fight. For the men of the 36th Infantry Division, training started with a refresher in military discipline and physical strength. Southwest men were proud of their rough and ready skills, but they did not translate as easily to military discipline as the staff of the AEF saw it. Therefore, training in France was to reacquaint the soldier to inspections, military courtesy and precision in all things. The next element of the training was fitness. The men once again became familiar with long hikes with their gear, this time over the hills, forests and valleys of northeast France.

The men also took bayonet practice and the Engineers built rifle ranges and grenade pits. The 36th Infantry threw their first live grenades at Area 13. In addition, they improved their marksmanship and became familiar with the new Browning Machine Gun and Browning Automatic Rifle (BAR). The 36th was the first division in the AEF to be equipped solely with BARs. The men made night marches and solved field problems. They learned to coordinate their movements with each other, but there were no tanks or artillery to train with in Area 13.

Despite the division’s spread-out existence in rural France, Area 13 was just 100 miles from the front line. The men were in frequent contact with soldiers from other units and other nations. As a result, they were learning daily of the war that was, at this moment in the war’s last summer, raging just out of earshot.