In the predawn hours of October 8, 1918, Captain Ethan Simpson prepared his men to attack. He tried to get more ammunition and grenades for H Company, 142nd Infantry. He also sent out patrols to make sure the enemy was not about to attack. In the dark of night Captain Simpson himself crossed the front line with a Marine guide to see what the Germans were up to. When two Germans appeared to see Simpson, his companion let loose with a shotgun and they both made tracks back to their foxholes.

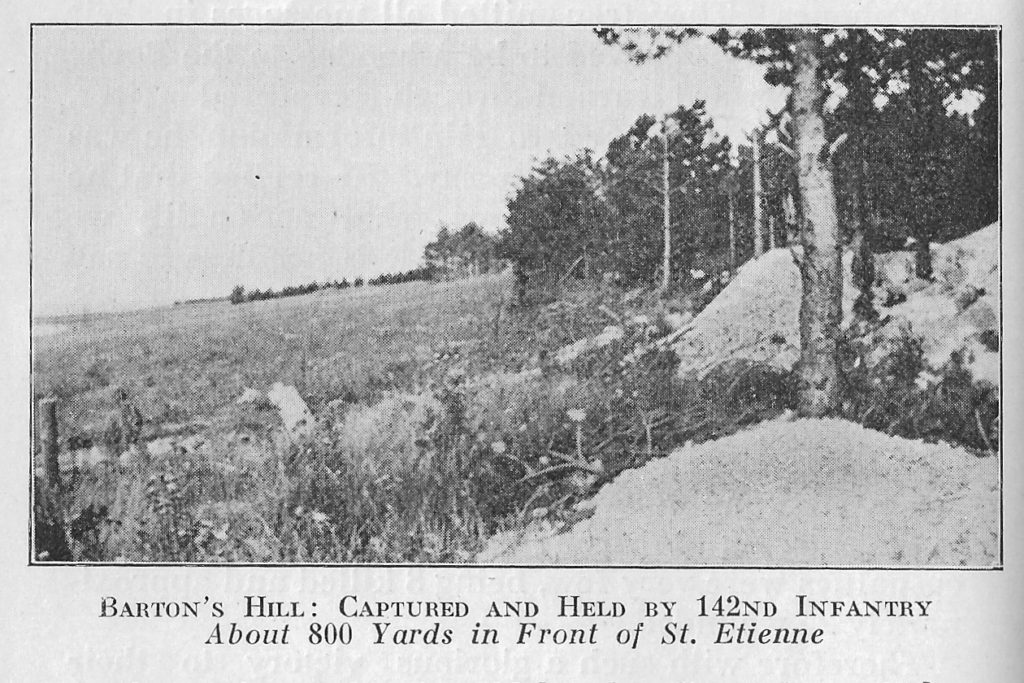

It was getting light. Captain Simpson was summoned to Battalion HQ for orders, where he learned that they would attack in a matter of minutes. His company would be on the right side of his regiment; the 141st Infantry would be advancing on his right. Likewise, Captain Thomas Barton’s G Company was on his left. Sixty to one hundred yards ahead of him was a stand of trees, and the enemy.

Ethan A. Simpson was a citizen soldier who had joined the army ten years earlier. Also, he had been an officer for nine years. In civilian life he was a lawyer in Clarendon, Texas, where he had recruited a company of volunteers in 1917. Some of those Panhandle men were still with him.

After an American and French artillery barrage that fell mostly off-target, H Company went over the top. The woods in front of H Company lit up with muzzle flashes from machine guns. As he advanced into the trees, Captain Simpson was hit by two bullets fired from a tree above him. But Simpson was able to find the German gunner and shot him dead. Finally, the wounded Captain was carried back to the American line.

Samuel M. Sampler

Corporal Sam Sampler was born in Decatur, Texas. He had lived in Oklahoma, but enlisted in the old 7th Texas Infantry in Quanah. On October 8th, Sampler was in Captain Simpson’s H Company when he saw Simpson and two other officers in the company hit by gunfire. As a result, H Company was halted by machine guns at the top of Hill 160. Nevertheless, Corporal Sampler took some German grenades and made his way around the nearest machine gun nest. His third grenade hit home and killed two of the gunners, silencing the machine gun. Consequently twenty-eight of the enemy surrendered and the American attack continued.

Harold L. Turner

Corporal Harold Turner of Seminole, Oklahoma, enlisted in the old 1st Oklahoma Infantry in Wewoka. On October 8th he was in F Company, 142nd Infantry on the attack just behind H Company. His company commander being wounded, Turner and his sergeant organized a platoon of runners, signalmen and battalion scouts. Advancing though enemy fire, Turner soon found himself with just four men unhurt. Four enemy machine guns were twenty-five yards away. When they shifted their fire away from his men, Corporal Turner charged them with his bayonet. Consequently, Turner captured the machine guns and their fifty-man crew.

For Extraordinary Heroism

For his actions on October 8th, 1918 near Saint-Étienne, Captain Ethan A. Simpson was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross.

For their actions on October 8th, 1918 near Saint-Étienne, Corporals Samuel M. Sampler and Harold L. Turner were awarded the nation’s highest award for heroism, the Congressional Medal of Honor. Only ninety-six Medals of Honor were awarded to ground soldiers and marines in World War I.

Learn more about the battle on the 8th of October:

Conspicuous Gallantry and Intrepidity

Resources

Texas Military Forces Museum: The 71st Brigade at St. Etienne