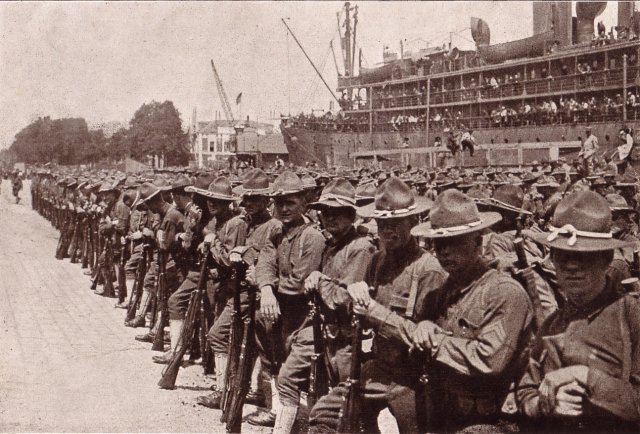

In the fall of 1917 American forces were making contributions to the Allied cause in Europe. Among the first to enter the war zone were American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) Engineers. In April 1917 the US Army created nine Engineer regiments for rapid deployment to France. Their job was to enlarge French ports: building docks, ship berths and storage facilities. US Engineer regiments would also build and repair thousands of miles of railroad track during the war.

One such unit, the 11th US Engineers, began in New York state in April 1917 with a force of 1,400 volunteers. Most of them had worked in railroads before the war. The 11th Engineers trained at Fort Totten, Queens until they were transported across the Atlantic, reaching England on July 27. When they reached France in August, they immediately went to work for the British Third Army in Flanders.

That’s where they were on September 5th when Company F came under attack by German artillery. The men of Company F were laying track in Gouzeaucourt, France when German shells fell. Sgt. Matthew Calderwood and Pvt. William Brannigan were wounded in the attack. They were the first combat soldiers in American uniform to be wounded in France in the war.

Cambrai

American Engineers were operating in the same zone almost three months later when the British launched the largest tank offensive of the war. The attack was focused on Cambrai, near the Belgian border with France. The 11th and 12th US Engineers were laying narrow gauge track to bring the tanks to the front line. They also had to get the machines off the railcars and prepare them for battle.

While the British tanks were punching holes in the German lines, German troops were coming through them in counterattack. On November 30 they penetrated British lines as far as Gouzeaucourt, where a company of the 11th Engineers was building a rail yard. The company retreated with their British allies to an old British trench system near Fins.

What rifles and ammunition the Engineers had with them they gathered there. But what happened next surprised the British officers who were organizing the defense:

“…I think Captain Hulsant was commanding the Gouzeaucourt party when the German advance fell upon them. Some had rifles with them, in the case of others they were far away, but that made no difference to these gallant Yankees. With spades and pickaxes they fell upon the advancing Germans and although many were knocked out, I was assured that they got the best of it in a hand to hand combat.

It was a brave thing to do; for surrender would have been easy and for once justifiable.”

First to Fight

Twelve US soldiers were seriously wounded in the fighting. Private Dalton Ranlet, 11th Engineers, was killed. But they forced the Germans back and even found Private Charles Geiger, who had been wounded and captured by the Germans. Seeing the allies advance, the Germans left their prisoners and fled Gouzeaucourt.

The British effort in what became the Battle of Cambrai was a bust; no real land was gained in exchange for over 47,000 casualties. Twenty-eight Americans were wounded in the unlikely action of the 11th US Engineers where they were the first to fight in the AEF.

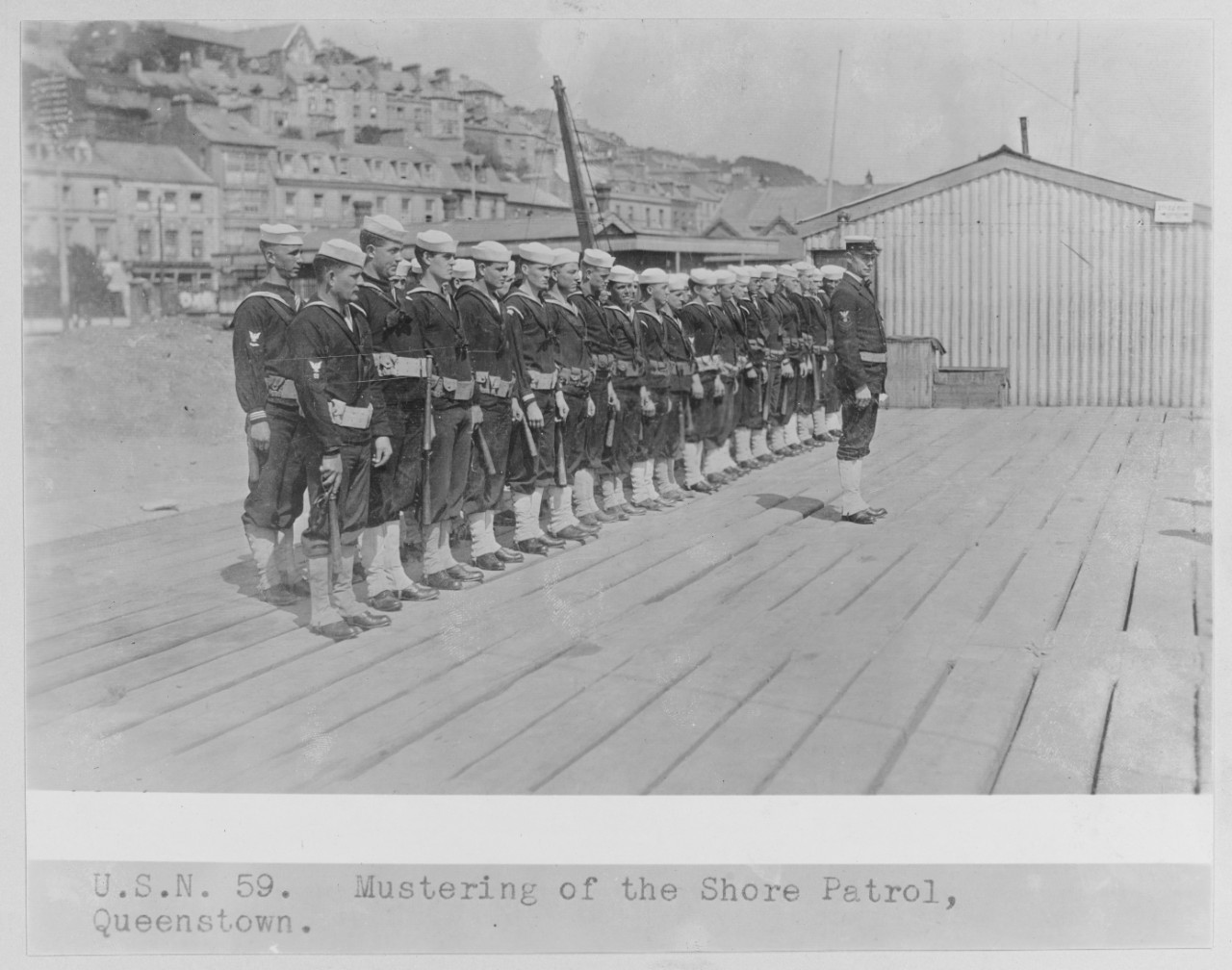

Queenstown

Late in the fall of 1917 the US Navy was patrolling the Western Approaches from its base in Queenstown, Ireland. Over forty American destroyers from Queenstown escorted convoys and hunted German submarines. They also rescued survivors when U-Boats struck. Queenstown harbor was full of American ships coming and going on patrol.

On November 17, 1917 two Queenstown based destroyers, USS Fanning and USS Nicholson, were escorting an inbound convoy when the Coxwain of the Fanning spotted a periscope about a foot above the waves. A torpedo appeared in the water but missed its target. Fanning and Nicholson raced to the scene and dropped depth charges.

The barrage brought up the submarine, U-58, which tried to escape on the surface. Nicholson fired at the U-Boat, scoring a hit. Fanning gave chase, firing from her bow. A few more hits from the Fanning and the crew emerged from the stricken raider with their hands up.

The American destroyers rescued thirty-eight crew from the U-58 before it sank off the Welsh coast. It was the first confirmed sinking of an enemy submarine by the US Navy in World War I.

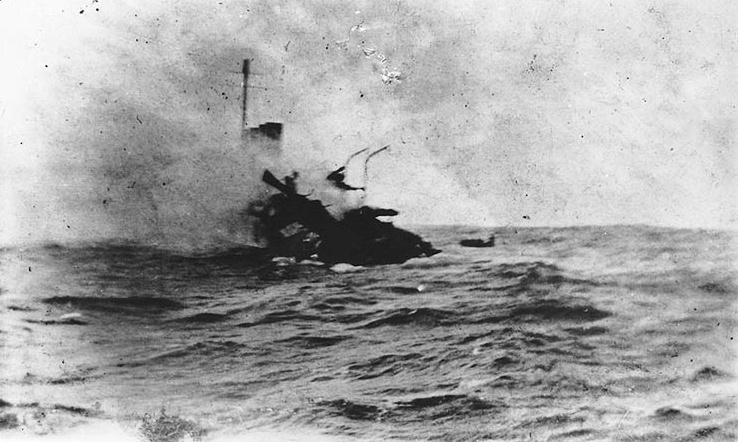

USS Jacob Jones

On December 6th another Queenstown based destroyer, Jacob Jones, was steaming back to base after convoy duty. As the destroyer approached the Cornish coast, lookouts spotted a torpedo to its starboard. Evasive action failed to clear the torpedo’s path, and the Jacob Jones was struck in the stern. The explosion ruptured an oil tank, which burst into flames and left the ship without power. Sinking in just eight minutes, exploding depth charges from the Jacob Jones killed some of the sixty-four men who died when it went down.

The men who survived on what boats and rafts remained were astonished to see a submarine, the U-53, surface fifteen minutes later. The U-boat took two badly injured sailors onboard and slipped beneath the waves.

Though the Jacob Jones had lost its radio mast in the initial explosion and was sailing alone, British vessels came to rescue some forty survivors within hours. In a rare humanitarian gesture in war, the German U-boat commander had radioed the position and drift of the survivors to Queenstown.