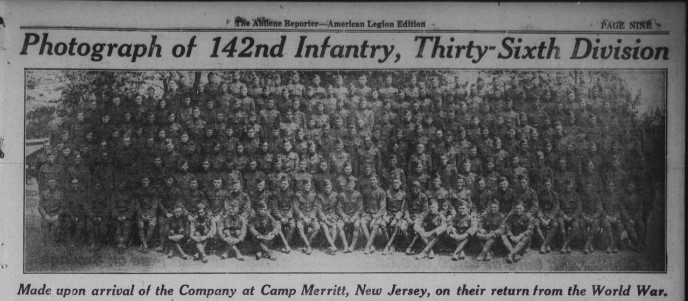

Back in the United States after almost one year, men of the 142nd infantry rested for a week at Camp Merritt in New Jersey. All of them would rather have been home instead of on the outskirts of New York. But it was significant as it was the last time the regiment was together. Although most of the soldiers of the 142nd were Texans or Oklahomans, a number from other states had been transferred to it. These men would not be making the journey southwest with the regiment. So, soldiers began to make their farewells during the first week of June at Camp Merritt.

Back in the Southwest

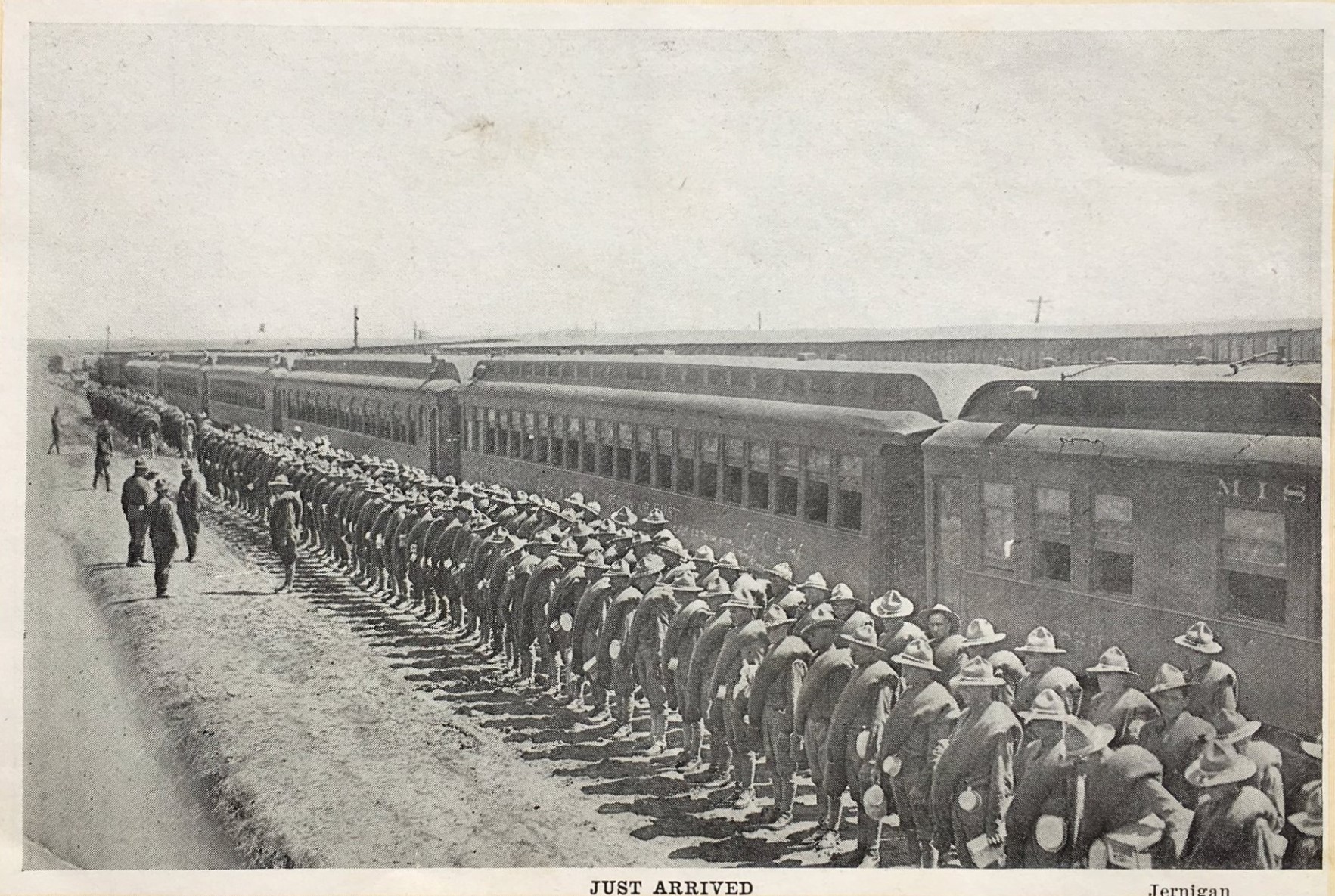

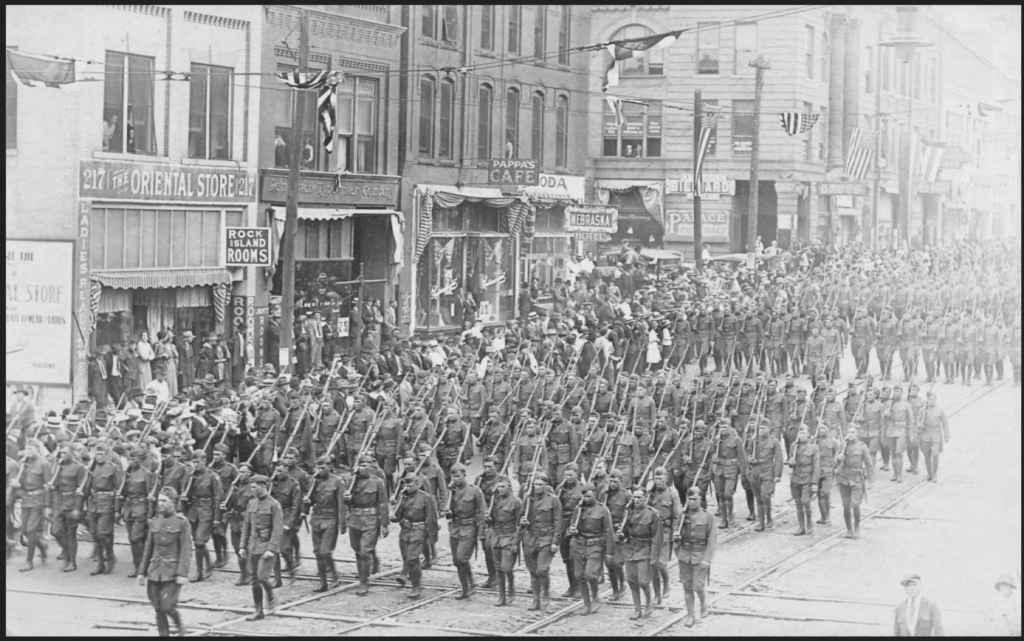

On June 8th, 1919, the 142nd Infantry Regiment entrained at Camp Merritt at 10 a.m. heading west. That night, they reached Cincinnati. The next night they had reached Springfield, Missouri. On June 11, the 142nd was in Enid, Oklahoma, where they marched through the streets to wild acclaim. Family members of soldiers were in the crowd, leaning in to get their first glimpse of a son, a brother, a husband. It was possible for these men to briefly reunite with family and friends, but the train had miles to go.

The next day, the train stopped in El Reno, Oklahoma City, and Chickasha. Each time, the whole regiment got off the train, looking sharp, and carried their rifles in formation down the main street. They were among the first Oklahoma servicemen to return from the Great War. The greeting they received was tumultuous, but all the soldiers really wanted to do was get home fast.

Camp Bowie

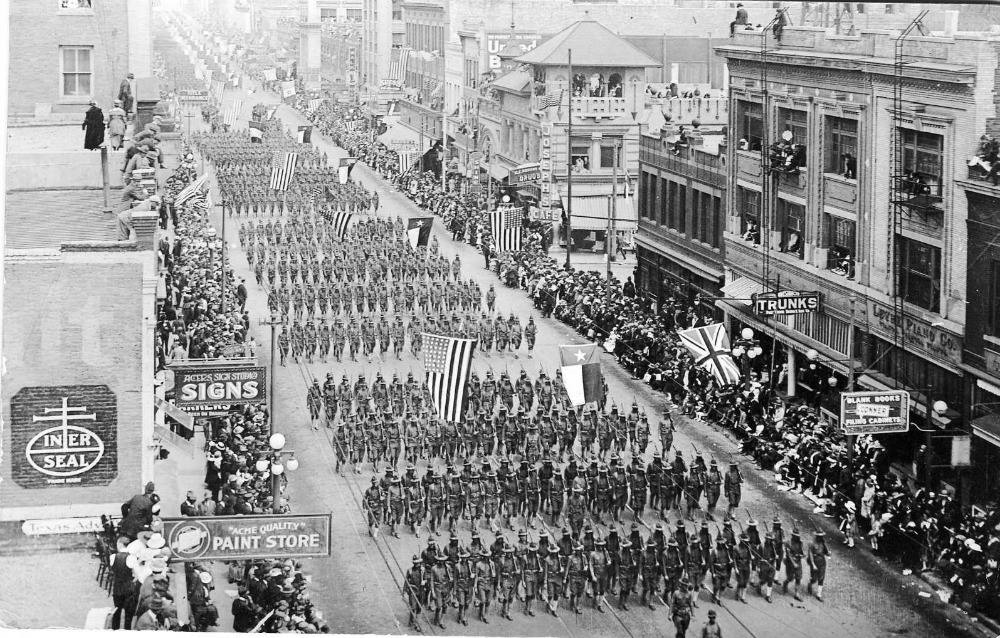

On June 13, the train finally stopped in Fort Worth, which the 142nd had last seen eleven months before. Experienced veterans stepped off the train at the place they had once been green recruits. Once again they marched through the main thoroughfares, but happily returned to the train to get to Camp Bowie. Camp Bowie had been converted to a Demobilization Center in late 1918. Soldiers from overseas had been processing through it since February 1919; so the crowd along the parade route on that day in June was not as boisterous.

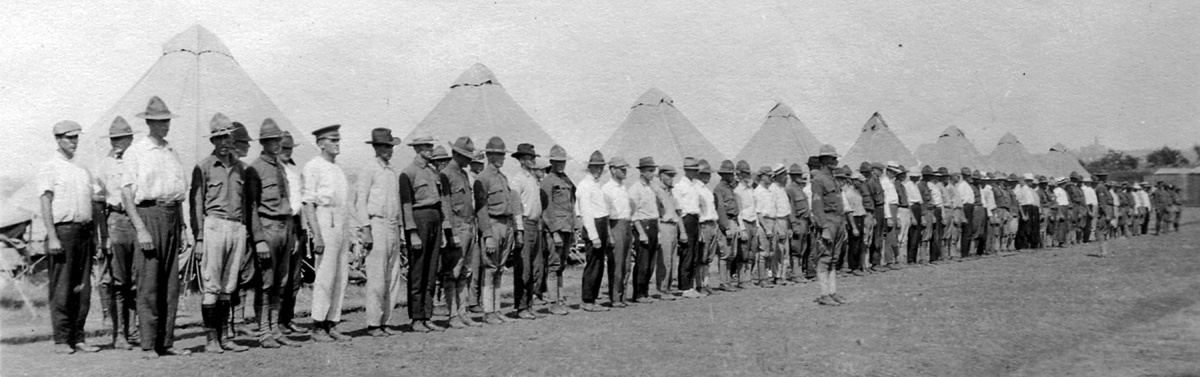

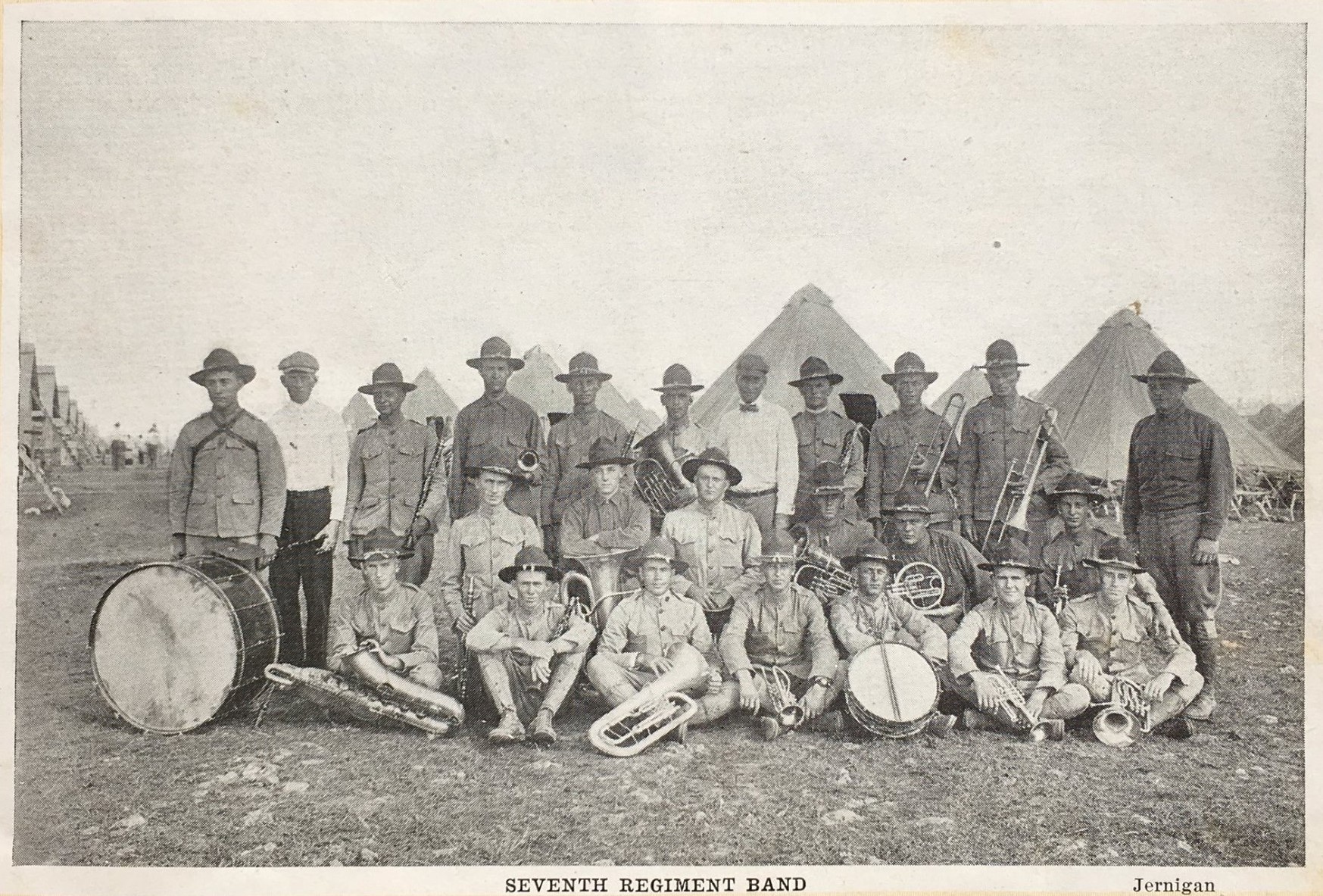

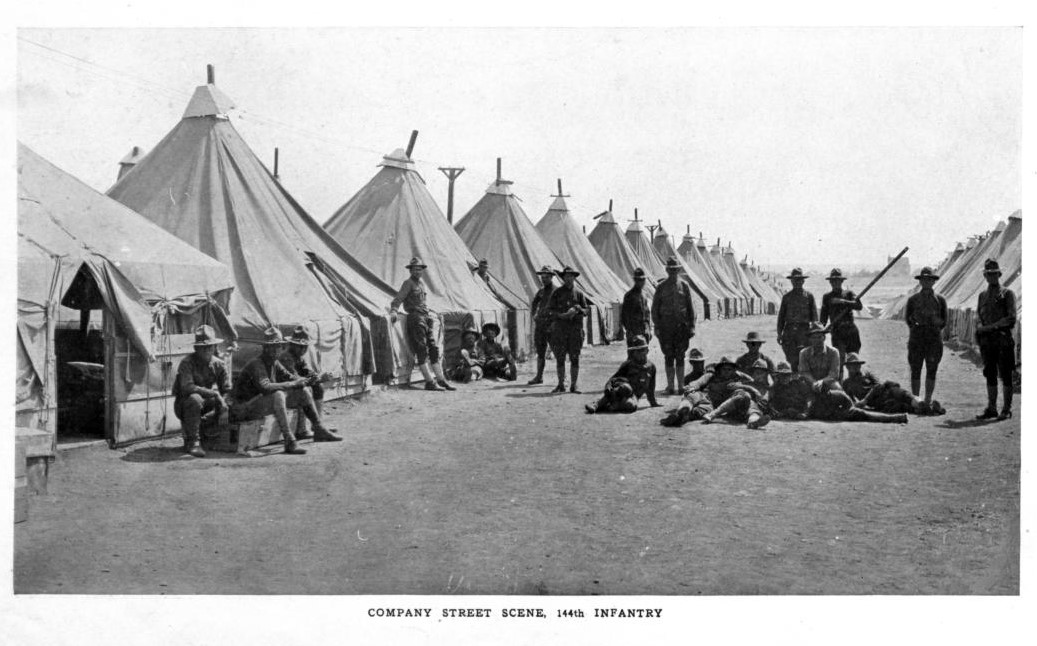

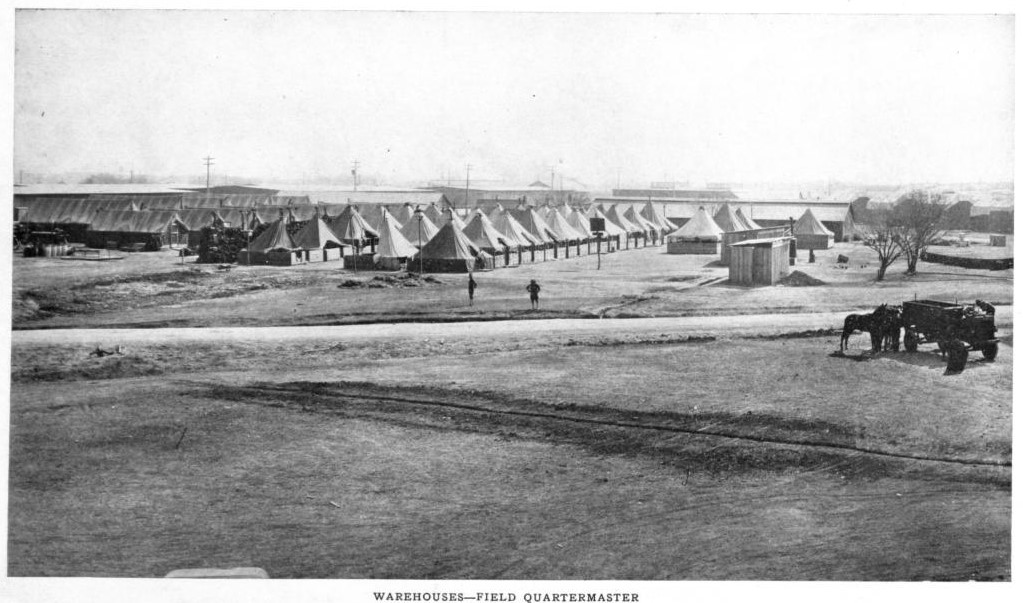

That is not to say that Texas was not happy to see its warriors come home. However, they were all coming home at the same time. Along with the other units of the 36th Infantry Division, the 90th “Alamo” Division was returning to Texas as well. Camp Bowie was a nest of activity as staff directed units to their tents and soldiers began the process of demobilizing out of the Army.

Demobilization

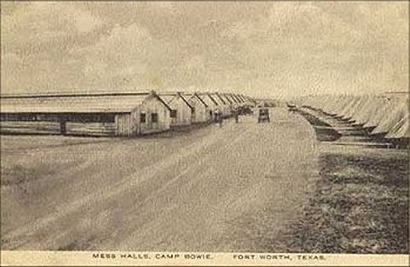

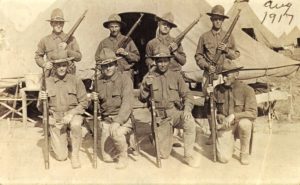

The process could take a few days, especially now that Camp Bowie was crowded. The 142nd found itself encamped in the area where the 61st Artillery Brigade was located back in 1917. Many, if not all of them, walked over to the area which had been their home at Camp Bowie for ten months. Soldiers turned in their rifles and all their equipment, keeping only their uniforms, shoes, gas mask, and helmet. There was a physical for all the men at the camp hospital. Then soldiers got in line to see the paymaster. Each one received his back pay plus a sixty-dollar bonus awarded to all soldiers returning from France.

Soldiers also received a travel allowance that paid for transportation to the location of their enlistment. Train tickets were sold right there in camp. There was an office of the US Employment Bureau for soldiers who wanted to apply for a job. The government also offered one last chance to purchase life or disability insurance before the men left the service.

“Farewell”

The men received their discharge paper from the Army. The moment had arrived; they were no longer working for Uncle Sam. “Oh boy, ain’t it a grand and glorious feeling” one ex-soldier exclaimed after he came out of the last barracks with his discharge. Friends and comrades who’d been through every stage of life in the service together now had to say goodbye. There was a train to catch or family waiting at the camp gate. Time did not allow for all that might have been said. But what they did communicate to each other in those few heady moments said it all.

On June 17, 1919, the 142nd Infantry Regiment stood down.

On June 18th, its parent organization, the 36th Infantry Division, was demobilized.

In the Hall of Mirrors in Versailles Palace, the Treaty of Versailles was signed by Germany on June 28th, ending the European war. The collapse of the Russian, German and Austrian Empires sparked fighting in Eastern Europe for two more years. Because of some of its provisions, especially the one establishing the League of Nations, the United States Senate did not ratify the Treaty of Versailles. A state of war existed between the United States and Germany until August 25, 1921.

The last American soldier left occupied Germany on January 24, 1923.

Remembrance

Ten years after the Armistice of November 11, 1918, the Llano Estacado chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution unveiled a memorial in Amarillo. It was dedicated to “The Panhandle Boys”, young men who went to war in 1917, some of whom would never get to grow old. A local department store published a tribute that day in the Amarillo Daily News,

“The rancors of the struggle have vanished long ago. With our generation will die the distant recollections of undersea destroyers, Liberty Loan parades and ghostly troopships fading down the misty reaches of New York Bay. But the memory of the lad who marched into the east on those long ago mornings shall ever remain sacred in our hearts and those of our children and our children’s children.”