In January 1918 Georgia O’Keeffe was still teaching art at West Texas State Normal College in Canyon, about 13 miles south of Amarillo. She had been chair of the art department there since fall 1916, but things were not going well. Since the entry of the United States into the war the previous April, Georgia O’Keeffe saw her community caught up in a wave of change that included her family.

Soon after she settled in her job at Canyon, O’Keeffe was joined by her younger sister Claudia, who was still in high school. Together they traveled through the Southwest, taking in the vast landscapes of Texas, New Mexico and Colorado. The stark expanse of light, sky and desert mountains mesmerized the O’Keeffes. It would be a life theme for Georgia’s art from the time she first moved to west Texas in 1912.

War comes to the O’Keeffes

Like many college towns across the country, Canyon, Texas was caught up in the enthusiasm of America’s entry into the war. Young men, students of O’Keeffe’s, wanted to enlist before graduating from West Texas State. Whether or not these men enlisted, many like them marched up main streets and participated in rallies nationwide. And townsfolk stood by and cheered. It was their way of supporting the war. But it was a low cost way.

Georgia O’Keeffe was brought up in Madison, Wisconsin in a large, close-knit family. Progressive and conscientious, the O’Keeffes were serious about their Christian faith and its commitment to nonviolence. So Georgia was very much troubled by the kind of patriotism she witnessed in her new home town of Canyon. She described the country being at war as “a state that exists and experiencing it in reality seems preferable to the way we are all being soaked with it second hand–it is everywhere…There is no-one here I can talk to–its all like a bad dream.”

…Personally

Soon after America entered the war, O’Keeffe’s younger brother Alexis enlisted. She visited him while he was in officer’s training at Fort Sheridan, near Chicago. She respected her brother’s sense of duty, but feared what it all might amount to: “A sober–serious–willingness appalling–he has changed much–it makes me stand still and wonder–a sort of awe–He was the sort that used to seem like a large wind when he came into the house.”

Back in Canyon, Georgia O’Keeffe felt more and more isolated from her neighbors and their casual anti-German attitudes. Texas had a visible German population at the time, as did her home state of Wisconsin. She was able to visit Alexis again, now a Second Lieutenant in the 32nd Infantry Division, while he was training at Camp MacArthur in Waco, Texas. His unit was the sixth Infantry division shipped to France in the war and would see heavy fighting, which is what Alexis wanted.

Alone

Georgia’s sister Claudia left Canyon in December 1917 for her student teaching assignment in Spur, Texas, 150 miles away. On January 2nd, the 32nd Infantry Division left Waco for France. That same month, Georgia O’Keeffe became ill in the first wave of a disease that had spread across the world, the 1918 influenza epidemic. O’Keeffe was very ill and took months to recover. In February 1918 she received medical leave from West Texas State. She moved to Waring, Texas, 450 miles away, to recuperate at the home of her friend, Leah Harris.

It was well for Georgia O’Keeffe to get out of Canyon. Her ambivalence about the war and dislike of jingoist descriptions of the enemy fed the rumor mill. Townsfolk began to view her as not patriotic enough.

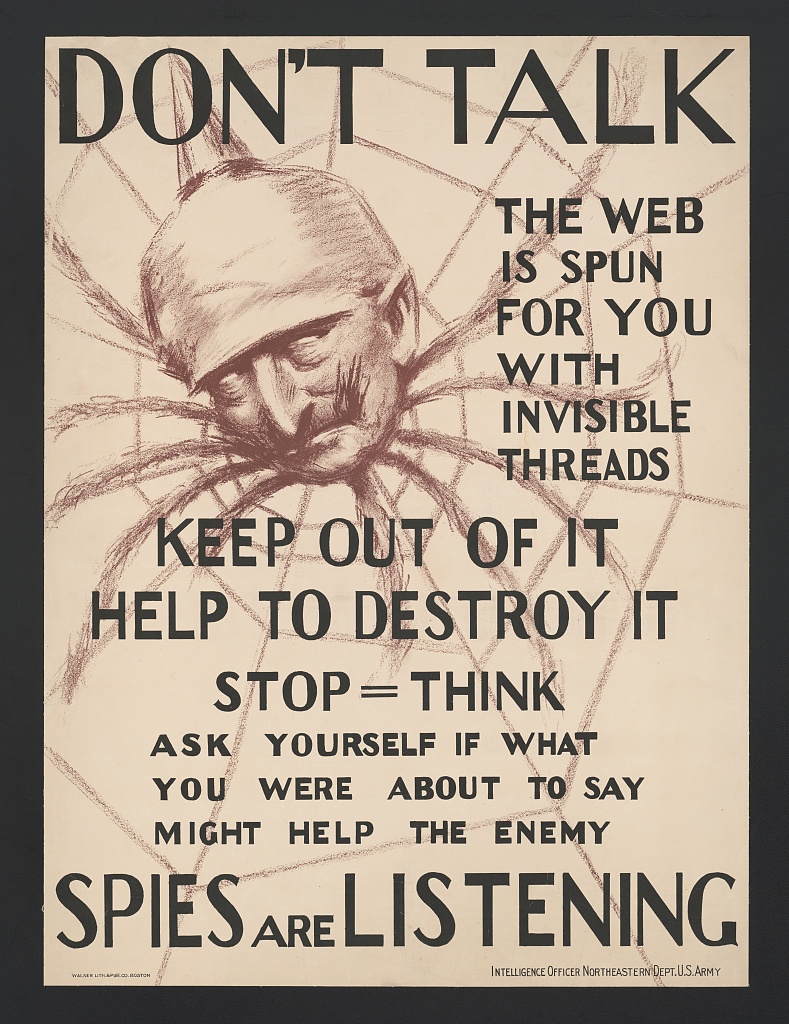

It was a scene that was repeated across the country. In June 1917 Congress passed the Espionage Act which criminalized any attempt to hinder enlistment or the draft. In May 1918, the Sedition Act also outlawed criticism of the government, the Constitution, the flag and the conduct of the war. The law was aimed in part against attempts from hostile nations to influence public opinion through the American press. But the law also made free debate of the war among Americans illegal, even in private.

The Flag

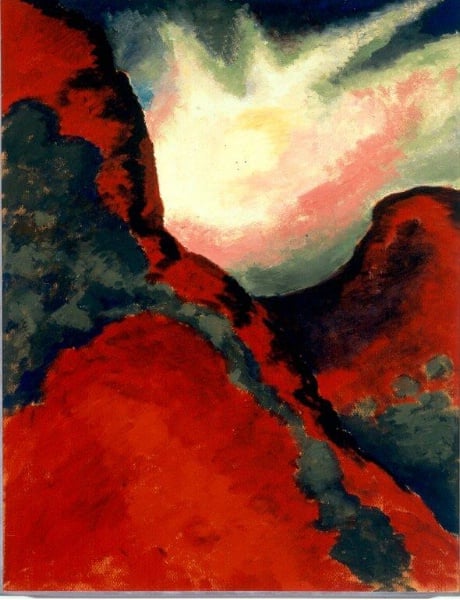

It was in this environment that Georgia O’Keeffe painted her most political work. The Flag is a deeply emotional and personal view of her crisis: True blue disappearing into a dark blue sky that blots out the stars, leaving only a streak of red. The flag battered in the storm.

Later in 1918 O’Keeffe would find out her brother was gravely injured in a gas attack while serving in France. Alexis O’Keeffe made it home alive, but in poor health. The Flag was never shown publicly during the war; doing so would risk violating the Sedition Act.

The Sedition Act expired at the end of the war and was never renewed.

Alexis O’Keeffe died of his war injuries in January 1930 at age 37.