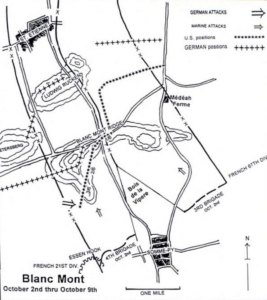

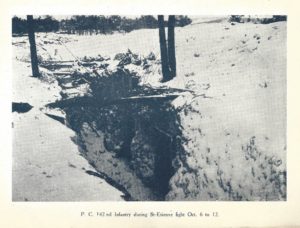

The American front line near Saint-Étienne was about to change. The 71st Brigade of the 36th Infantry Division had been on the attack for three days. After heavy casualties, it had lost the ability to advance further. The 72nd Brigade was on the way. Because of the distance and the danger of the battlefield, getting to the fight would take time.

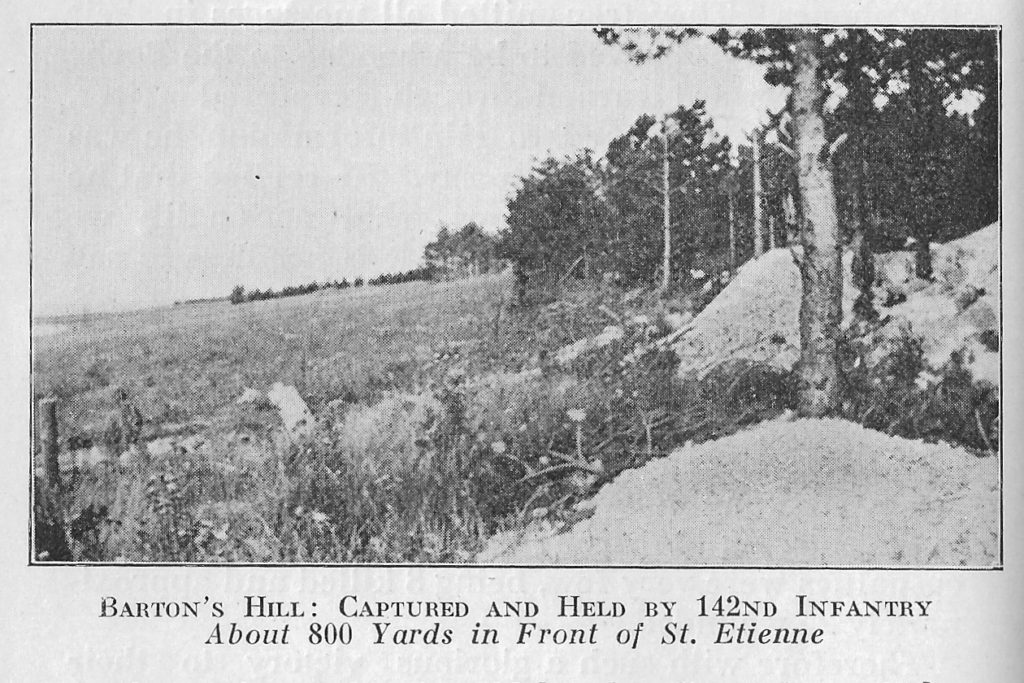

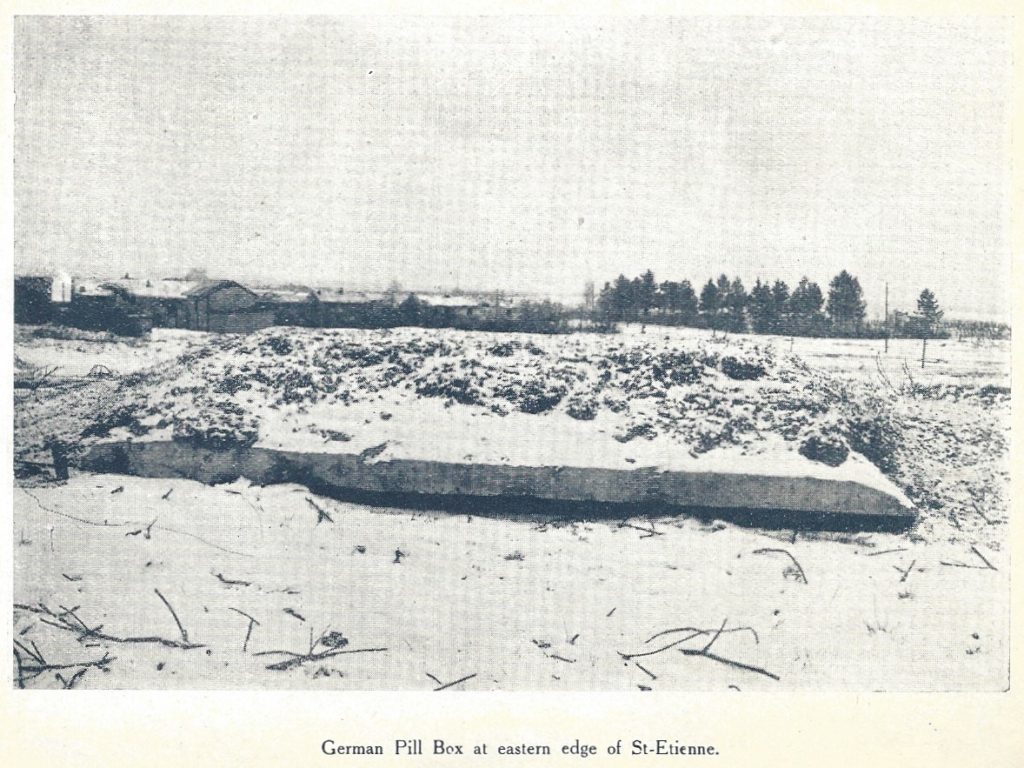

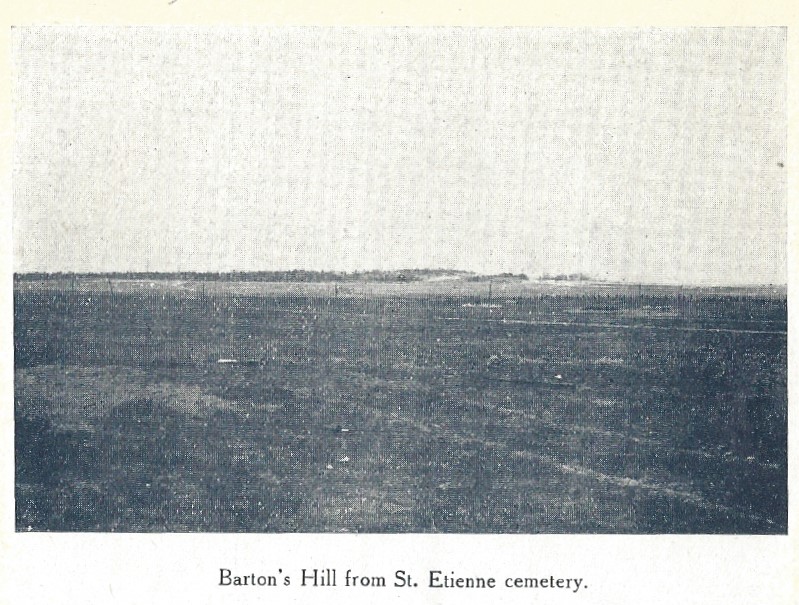

On October 10th, 1918, soldiers from the 72nd Brigade were on the battlefield. Getting all the way to the front was a challenge because it was hard to find. Now that the Germans saw them arriving, it got a lot harder. A tremendous artillery barrage greeted the 36th Division as it moved into place. Hits registered miles behind the American front line. The 142nd Infantry Regiment, now in control of the village of Saint-Étienne and across the flat landscape all the way to Barton’s Hill a kilometer away, would have to hold on for one more night.

As evening faded into night, the Germans continued firing flares into the sky. The flares would light up the night as they slowly descended by a tiny parachute. This would give enough light to expose anyone unlucky enough to be outside his shelter. But as the night wore on, the flares grew more infrequent. The night before, soldiers on the American side also saw large fires, three of them, behind German lines. Artillery shells came down on the American line as always, but less often.

October 11

In the predawn light, it was necessary to go out there to see what was happening on the German line. Several patrols of 142nd soldiers carefully made their way out of their foxholes and toward the enemy. One patrol came back to their unit in front of the village having heard a man cry out for help in English. It could be a German trap. In the morning mist, two Americans ventured in the direction of the voice.

After a short but intense period of silence the two men returned, supporting between them Private William Schaeffer from Company A. Private Schaeffer had been hit in the knee three days before, on October 8, the first day of the attack. When the Germans counterattacked, he was unable to make it back to the American line. Schaeffer hid in various places until his canteen was dry. As he crawled toward his comrades, he was close enough he could hear Germans speaking to each other.

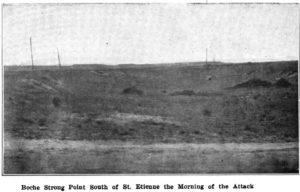

As the sun rose on October 11th, machine gun fire from the German side ceased for the first time. It was a cold morning and still misty, therefore the enemy could not be seen. More patrols set out toward the German line. They returned with the news that the outposts were empty.

The 71st Brigade, 141st and 142nd Regiments and a Machine Gun battalion, stood down. Just three days before, they had been untested in combat. Since then they had experienced ferocity, violence and privation that had chewed up the veteran division they replaced. Now they were being replaced by the 72nd Brigade.

The cost

It was time to call the roll of survivors. Leaders of battalions set up posts on different parts of the battlefield and each soldier made his way to his own company. Men of the same company who had not seen each other in days were reunited. In every gathering the weight of what just occurred was almost too much to bear. Two company commanders were killed. Seven Lieutenants were killed. Several companies had all their officers killed or wounded.

One hundred sixty enlisted men and ten officers of the 142nd Infantry were killed in that first engagement. The regiment was 40% understrength when it went into battle. This was due to illness and transfers. In addition to the dead, six hundred thirty-five men were wounded or missing. At least four of the missing were taken prisoner. As they gathered at their battalion outposts, battalions looked like companies. Some companies were headed by sergeants.

Reorganizing the men took all day on October 11th, as the 72nd Brigade moved forward to look for the retreating Germans. As men gathered and new leaders were assigned, food and supplies were moved forward. The division’s cook wagons arrived, and the men sat down to their first warm food since breakfast on October 6. In a quiet to which they couldn’t yet adjust, the 142nd regiment slept on the battlefield once more.

Leaving Saint-Étienne

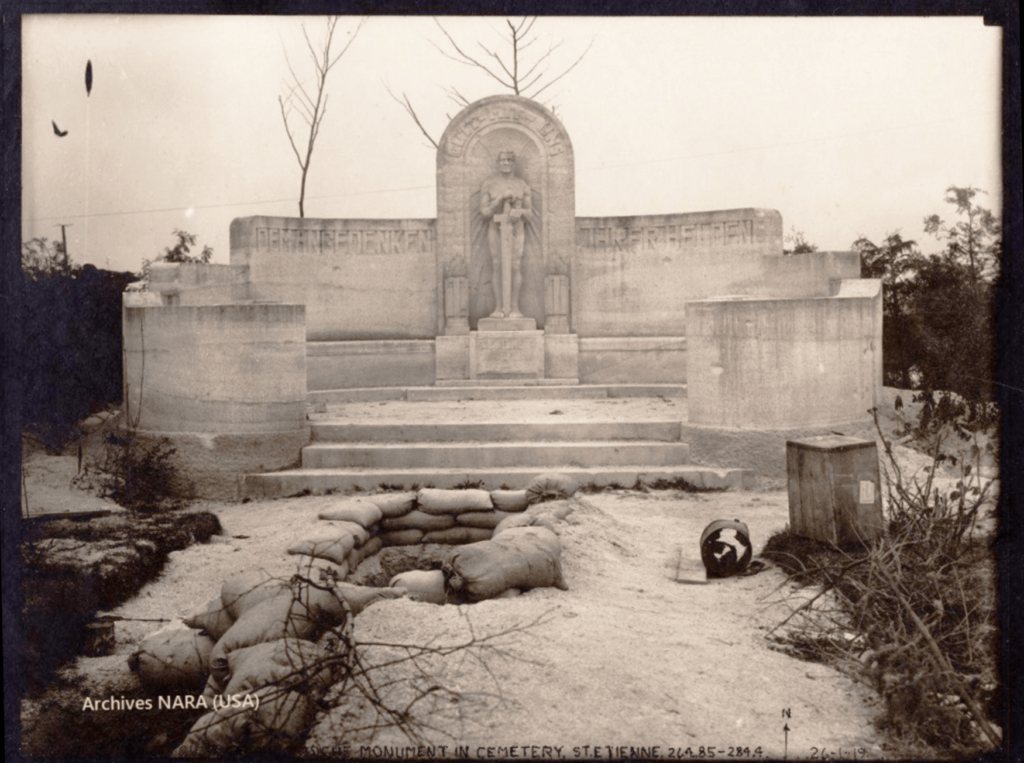

On October 12th the regiment buried their dead. As the men searched the battlefield, their loss was magnified by the remembrance of each friend and neighbor laid to rest in the fields of France. Marines and Engineers from the U.S. Second Division were among the dead and men from their units were able to give their comrades a respectful burial.

Although the battle of Saint-Étienne was over, war continued. Men of the 142nd joined the mass of their division marching north toward Germany’s industrial heartland. Because they occupied the battlefield, the Americans could consider themselves the victors. But it was at a terrible cost. Germany, which invaded France to protect that heartland, moved out in an orderly retreat. They too had won something, if only time. The cost to them had been great as well.

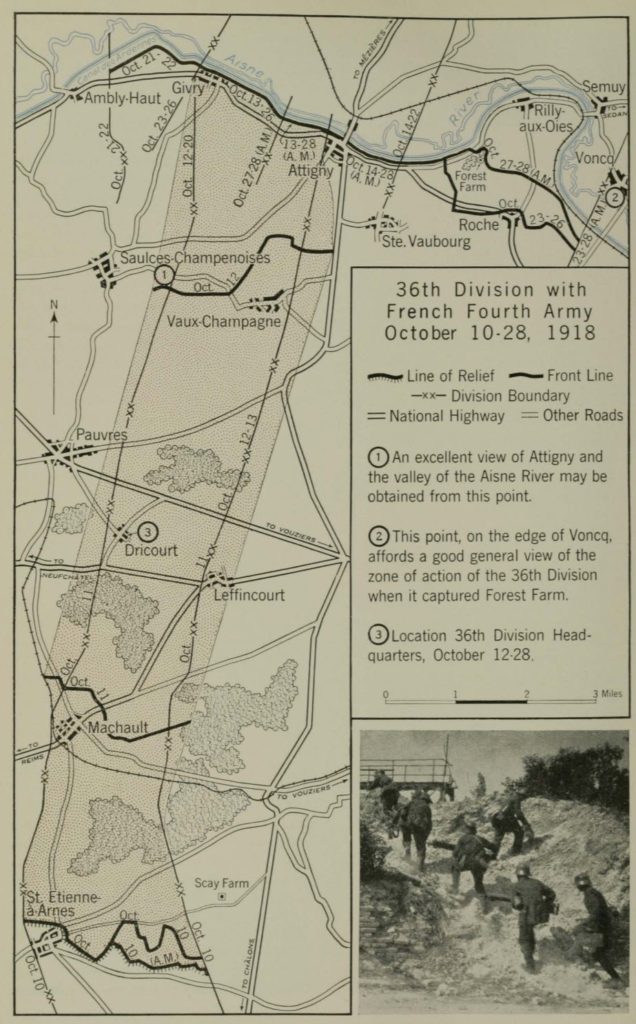

The German withdrawal had been comprehensive. Units began retreating days before October 11th. Artillery had rolled back under the cover of heavier guns far to the rear. Soldiers of the 72nd Brigade only encountered a small residual force after advancing two kilometers north of Saint-Étienne. By the end of the first day they had overtaken Machault, four miles to the north. There the Germans had burned their stores, the fires the Americans had seen two nights before.

The Aisne

The men of the 142nd followed the American advance on October 12th and had reached the vicinity of Dricourt, about seven miles away from Saint-Étienne. Late in the day, the cook wagons were in place and the men were able to get a hot meal. Although now it was raining, the 142nd Infantry made shelter as best they could in a stand of pine trees and stayed the night.

On October 13th the 142nd marched about eight more miles toward the new front line. The Germans had retreated fifteen miles to the north bank of the Aisne River, near Attigny. The river and the Ardennes Canal, which ran parallel to the Aisne, was the new front line. The men of the 142nd were once again in range of German artillery, firing shots at random at the countryside. As night approached, the men moved toward the river. It was still raining, but by midnight the leading units of the 142nd Infantry had made their way to the banks of the Aisne. What the enemy was up to on the other side, no one knew.