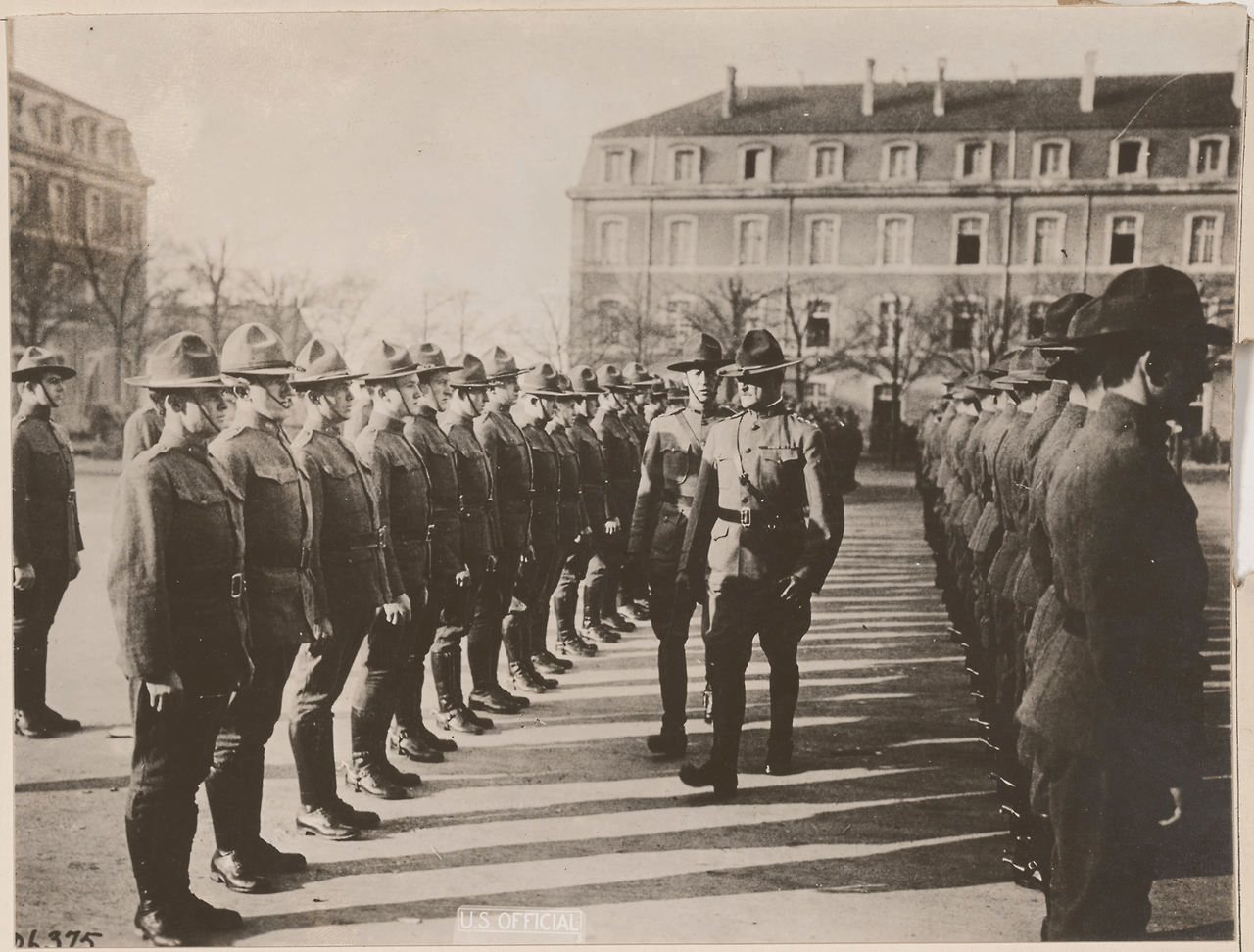

By July 4, 1917 the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) had 16,440 troops in France; just over half a division. The French people were ecstatic to see Americans after nearly three years of war. But Major General John Pershing knew his fight was to grow an American army in France.

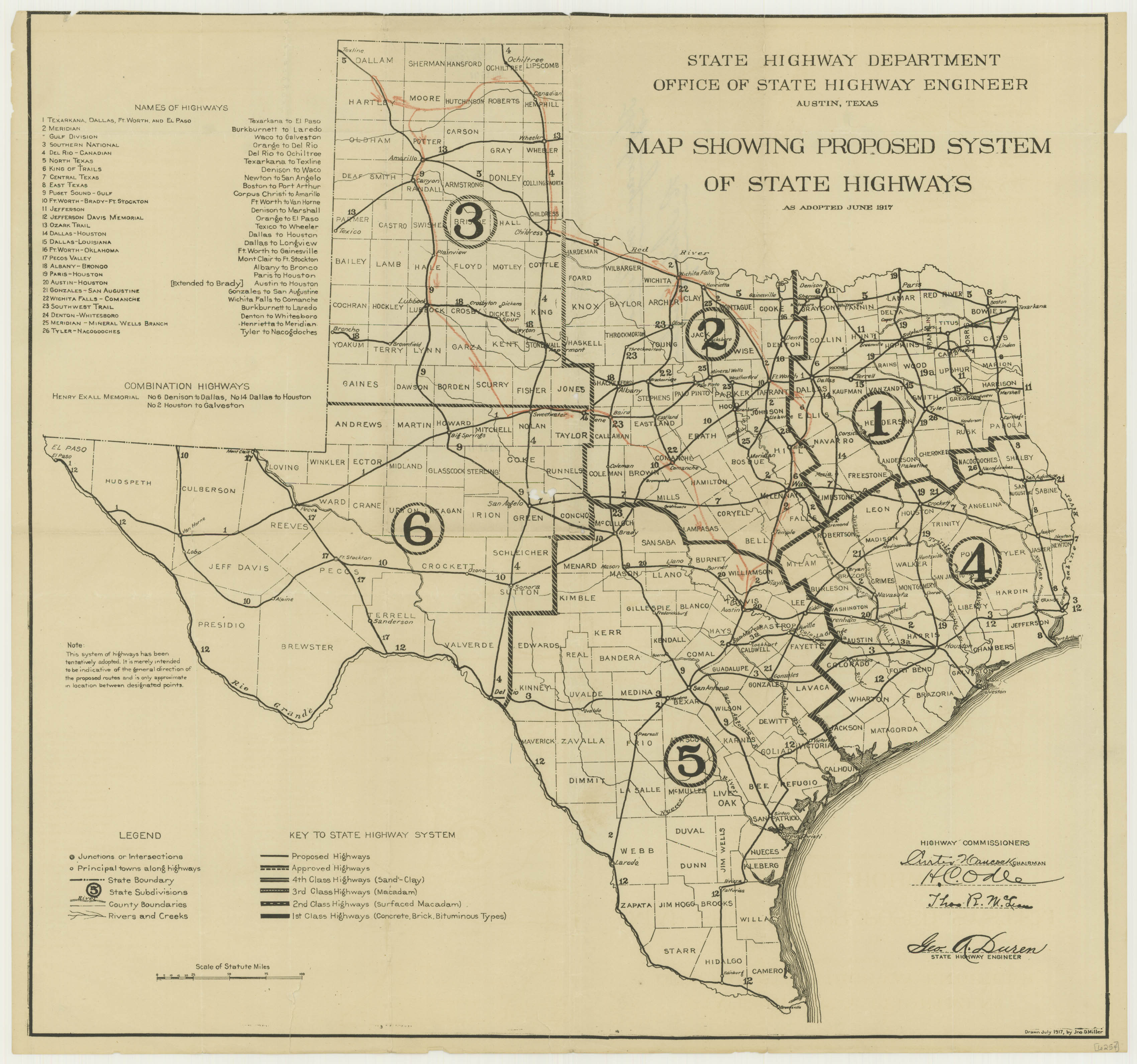

General Pershing’s first challenge was transportation. As he was preparing his headquarters in France during the summer of 1917, over one million men were entering the armed forces at home. That summer Pershing and his staff requested that Washington send 30 infantry divisions to Europe by 1919. These infantry divisions, plus artillery forces and other services, would form a freestanding American army. It would fight alongside the French and the British Empire forces on the Western Front.

This plan did not sit well with the French and especially the British. At the time they were fighting in trenches along a 700-kilometer (nearly 450 mile) front against an emboldened enemy. Millions of enemy troops were fighting on the Eastern Front against Russia, but this war was changing in the Central Powers’ favor. Russia’s severe losses in the war had caused Czar Nicholas’ abdication in February 1917. Although the war In the East dragged on through 1917, Germany and Austria-Hungary could now give the West more of their attention.

The Allies test Pershing

As the enemy was gaining momentum in 1917, the Allies were having a bad year. A massive French offensive in the spring had gone so badly that hundreds of units in the French army simply refused to go over the top of their trenches anymore. In addition, British and Empire forces experienced horrific losses during their own hundred-day battle in northwest France and Belgium near Ypres. Similarly, Central Powers armies pushed the Italian front back sixty miles in the fall.

The Allies (French and British Empires; Woodrow Wilson called America an “associated power”, not an allied one) were desperate for men. Their losses included the loss of confidence in their political and military leaders. French and British people were growing tired of war. The grim sacrifice of so many young men for so little gain brought them close to despair. The western Allies had the weapons and experienced leadership, but they were running out of men.

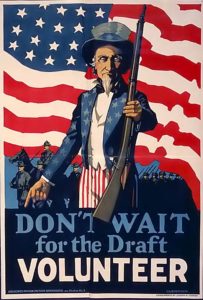

America had men. One million men were in training stateside in 1917. Potentially many more could be drafted. As a result, France and Britain were interested. Could the United States merely send the men, and let the Allies equip and command them? The French suggested that American units could be interspersed with French in a bi-national Army under French control. There would be no need for American generals, just field troops.

The British plan was even more outrageous. Since there was no language barrier, new American recruits should just don British uniforms as soon as they crossed the Atlantic. Then they could join the fight as an Anglo-American Army led by British officers. This would lead to the quickest victory in the West, they believed, at a time when defeat was a real possibility.

Walking the tightrope

Pershing was having none of it. American soldiers were not going to wear British uniforms or join French regiments. The U.S. Army was going to fight in France as an army and not as a client in the Great War. The pressure on him was great, however Pershing did not give up. He envisioned an American army victorious in an American sector of the Western Front. In any case, Pershing shared this view with his superiors in Washington all the way to the White House.

But as a small “a” ally, Pershing knew he needed the other two to reach this goal. Great Britain had the ships he would need to help get soldiers across the Atlantic. Similarly, the Allies had weapons and equipment these soldiers would need in France. They also had experienced soldiers needed to train untested Americans how to fight a complicated machine age war in Europe.

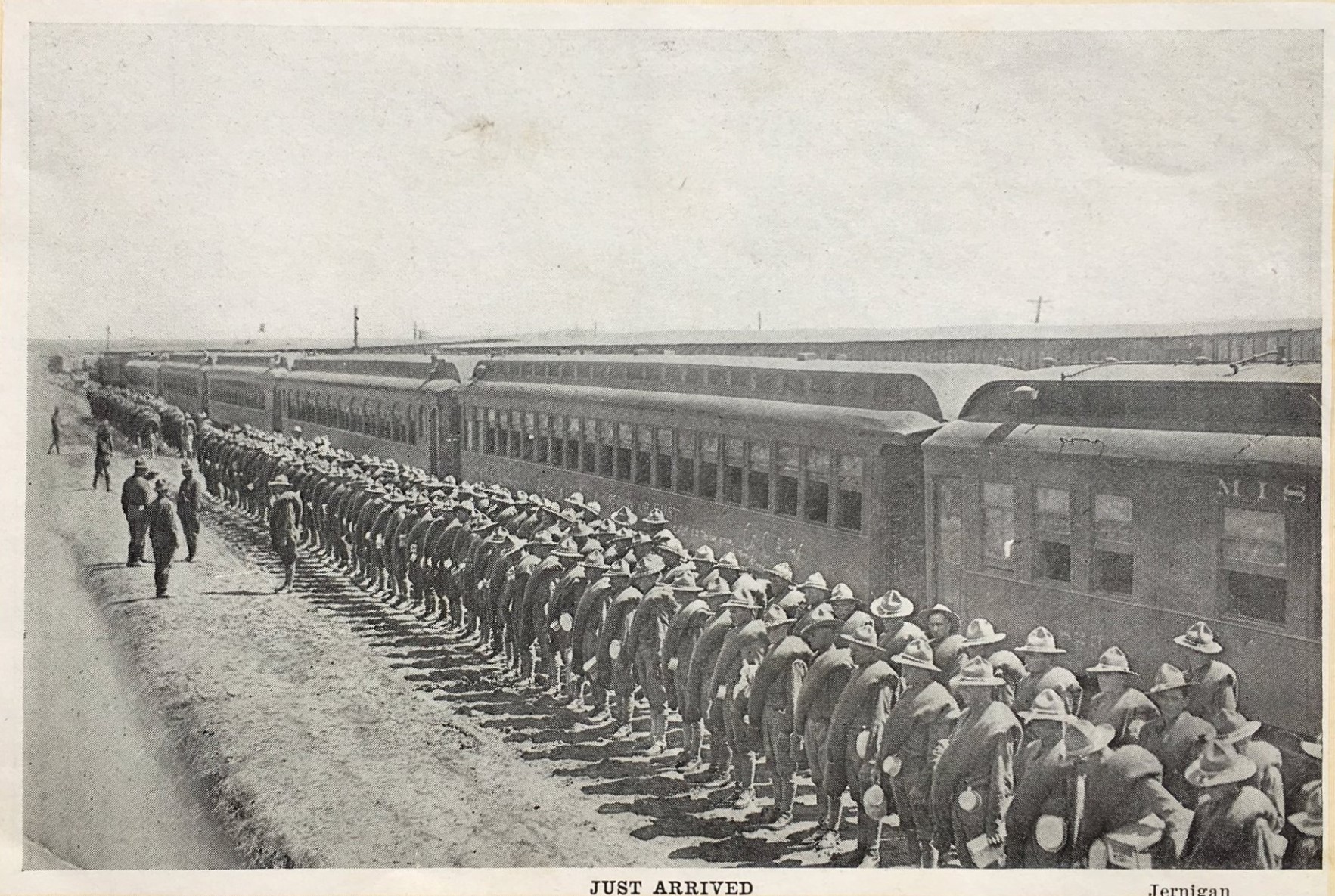

So some compromises were made. Transporting American infantrymen became the priority for Allied shipping, often to the detriment of artillerymen, artillery and war materials from the States. American units would first go into the front line in quieter sectors under French command until they were experienced in combat operations. But the tension of American manpower in the European war never really went away.

Preparing for the day

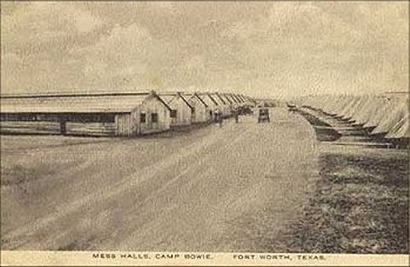

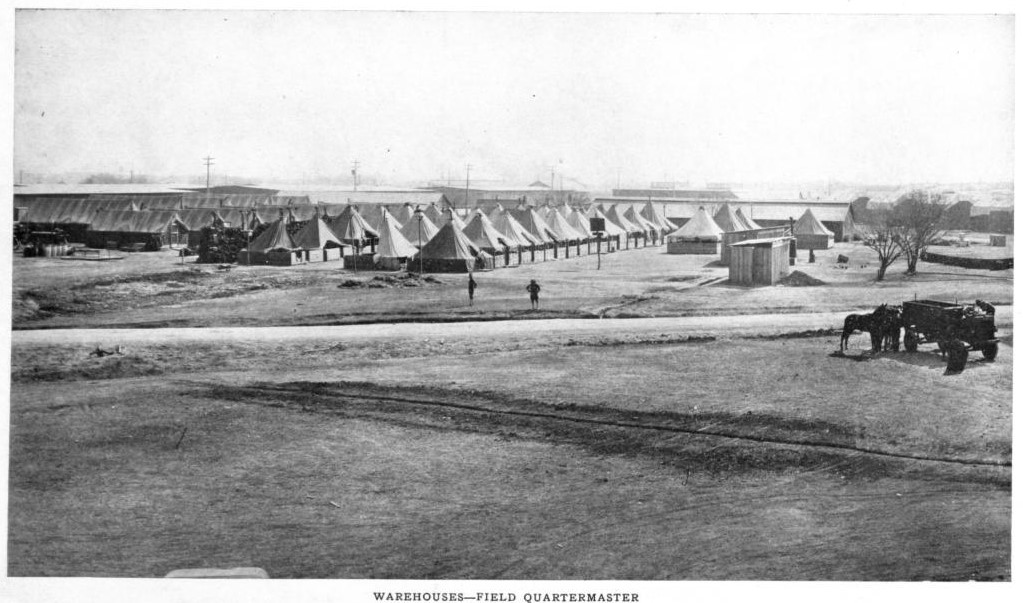

In the summer of 1917 and after, General Pershing put together an Army command that shared his vision and his urgency. His most important creation was likely his logistics command, called Services of Supply. Thousands of soldiers and engineers created an infrastructure to receive, transport, arm and feed this new American army. They enlarged four Atlantic harbors in France, adding 82 berths for incoming ships. One thousand miles of standard gauge railroads were built to move their cargoes. One hundred thousand miles of wires were strung for use by the AEF in France.

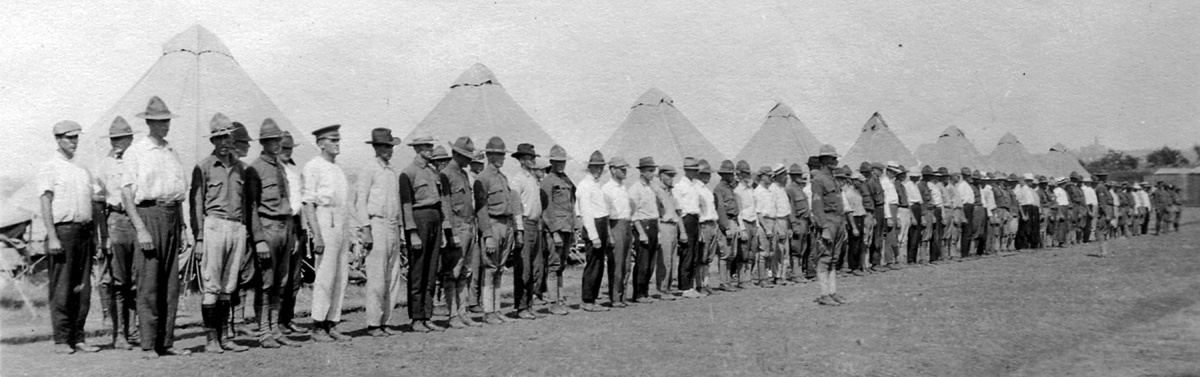

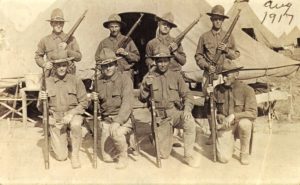

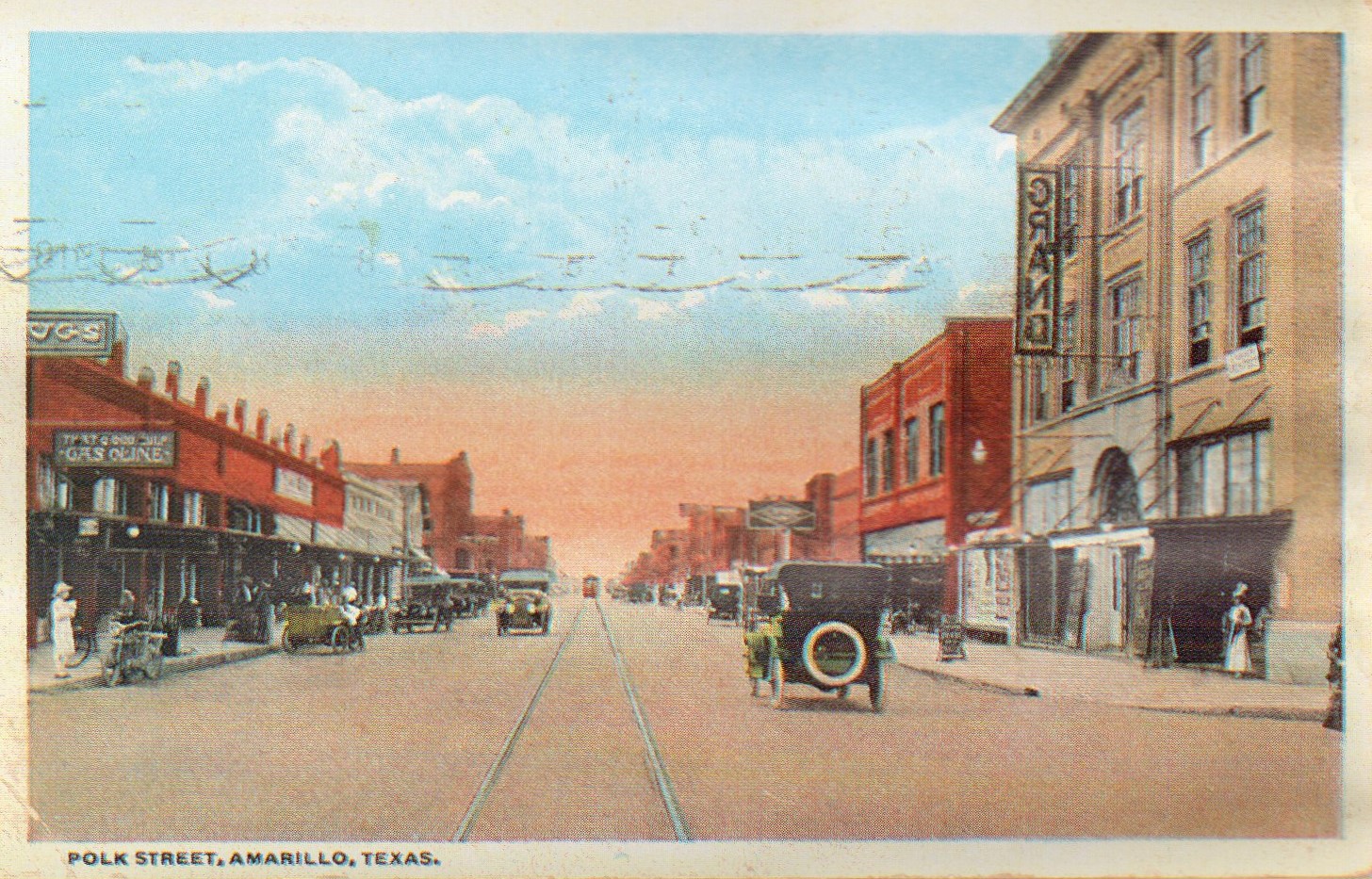

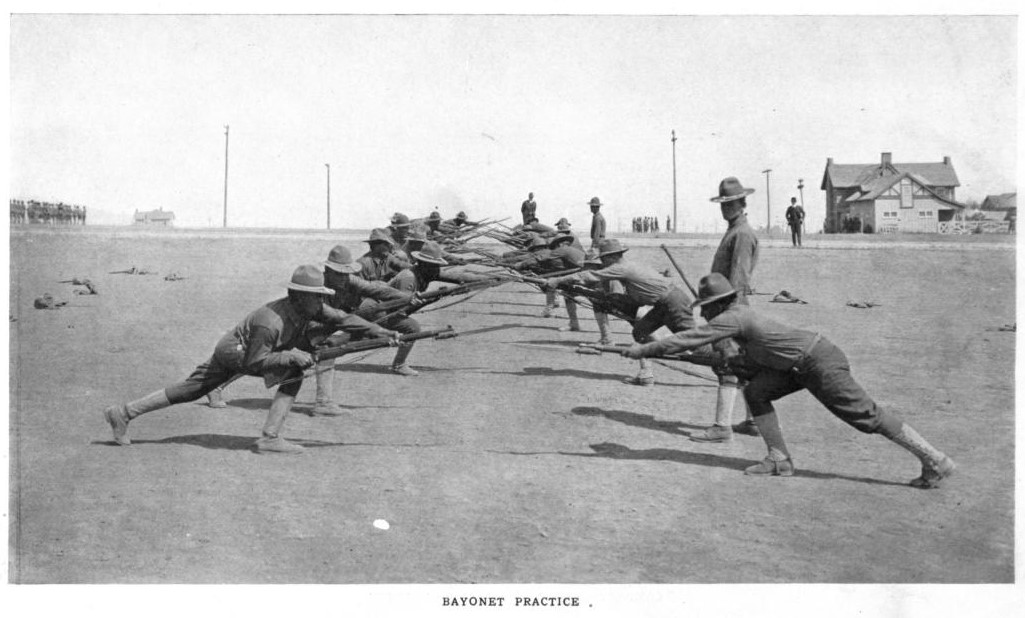

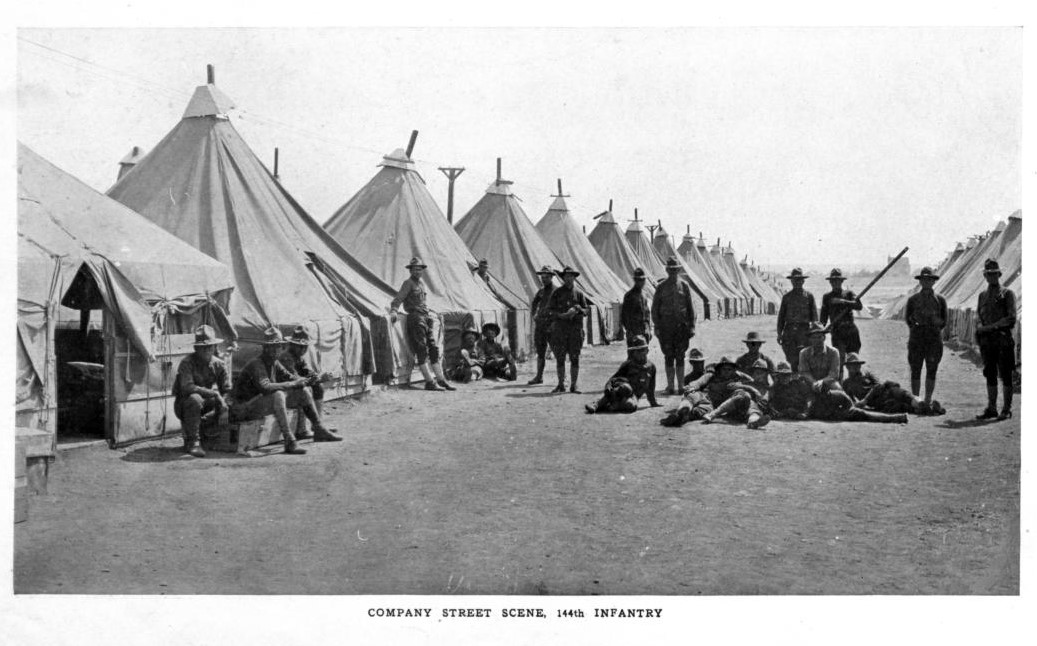

In the United States, staging areas were built near the ports of New York City, Hoboken, New Jersey and Newport News, Virginia. America prepared to send men and materiél on an international fleet. In fact, some sailed on ships seized from the enemy. When they got there, training camps were built where soldiers learned to fight together in ever larger formations. Their teachers were veteran French and British soldiers, who had seen it all. By the late fall of 1917, Pershing had most of four infantry divisions in France, 78,000 men. They were willing to go into action, but time would tell if they were ready.

Base Hospital No. 5

The Army Medical Corps was the first to be ready. During the Border war with Mexico, the Medical Corps and the American Red Cross organized a number of mobile hospital units that would move toward the front lines when activated. These units were organized around teaching hospitals and medical schools. In addition, many of the medical and nursing staff were already coworkers in civilian life.

Army Medical Corps units were mobilized and embarked for Europe in early May, 1917. The first unit arrived on May 18 and by mid-June, six U.S. Army hospital units were operating in France. On July 14, 1917 Lieutenant Louis J. Genella, a physician in the Medical Corps, was the first in American uniform to be wounded in action when his hospital unit was shelled southwest of Arras. Beatrice M. MacDonald of the U.S. Army Nurse Corps was badly injured when the Germans shelled her forward triage unit at Dozinghem, near Proven, Belgium on August 17, 1917. (See Nurse Beatrice MacDonald’s Distinguished Service Cross citation here)

Base Hospital No. 5 was organized in February 1916 in Boston at Harvard Medical School. Doctors, nurses and a core hospital staff were already training from that time. When war was declared with Germany a full unit, about company strength, was recruited and trained.

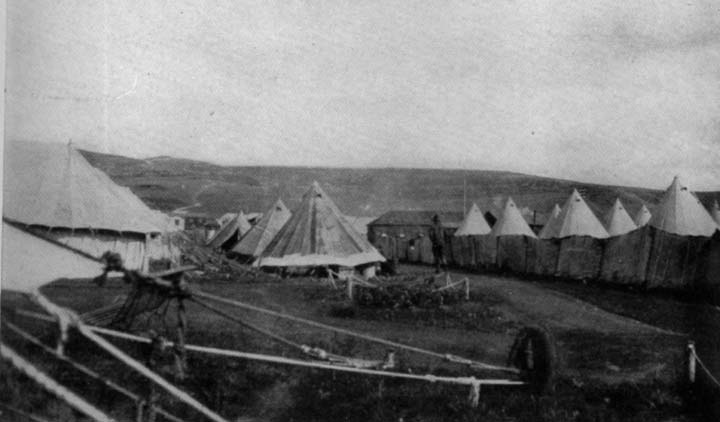

Base Hospital 5 was one of six evacuation hospital units requested for immediate service with the British Expeditionary Force (BEF). These units worked in tents and temporary buildings near the front lines as a first stop for wounded and ill soldiers. For example, they had X-Ray buildings and operating rooms, triage offices and nursing wards. They were the first line in a care system that could get the badly wounded Tommy into a hospital in England within twenty-four hours.

Into the war

The men and women of Base Hospital No. 5 left Boston on May 7, 1917. By May 11, they were on the British steamer Saxonia making way from New York to Falmouth, England. As the first Americans in uniform to land, they received a tumultuous greeting in England. After that, they quickly transited through England and crossed the Channel to France. Base Hospital No. 5 was greeted to even wilder acclaim in Boulogne on Memorial Day, 1917.

The unit was first embedded next to a British Hospital unit, General Hospital No. 11, in Dannes-Camiers. Camiers was on the coastal plain near the Pas-des-Calais. Soon Base Hospital No. 5 had taken over staffing the hospital. They were prepared to care for five hundred patients. However, the hospital was sometimes filled to 2,000 patients during the Ypres offensive that summer.

On September 4, 1917 Base Hospital No. 5 was attacked by a German bomber. Privates Oscar Tugo, Rudolph Rubino, Jr., Leslie Woods and Lieutenant William Fitzsimmons were killed. Lieutenant Rae Whidden later died of his injuries. They were the first in American uniform to die in France in World War I.

During the attack four members of the hospital staff were seriously injured, as well as twenty-two patients. You can read more about Base Hospital No. 5 here